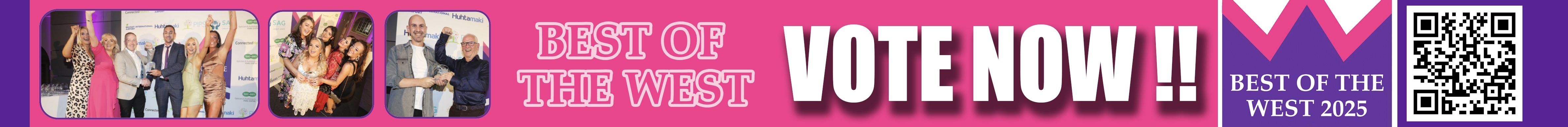

We Play Here by Dawn Watson (Granta Poetry, 3/8/23)

Taking Liberties by Leontia Flynn (Cape Poetry, 28/8/23)

Up Late by Nick Laird (Faber and Faber, 1/6/23)

INTRODUCING a recent reading at the Seamus Heaney HomePlace in Bellaghy, Damian Smyth, the Head of Literature at the Arts Council, said words to the effect that in this part of the world we’re in the front row for the appearance for some of the best new poetry being written anywhere in the world. The three books I’m going to recommend this week are all written by staff at the other Seamus Heaney Centre, the research department at Queen’s.

When I was in my early twenties I couldn’t get enough of the first books by Leontia Flynn (These Days from 2004) and Nick Laird (To A Fault from 2005): they were artful and relatable in equal measure. The opening poems of both books still surface in my head at unexpected times. I can imagine similar things happening with Dawn Watson’s debut book, We Play Here.

We Play Here is a series of vignettes showing the lives of four friends in north Belfast in the 1980s at the cusp of childhood and adolescence. The high-wire act that defines this book is Dawn Watson’s ability to simultaneously render a childlike vision of a particular moment and the haze with which one looks back on the past.

It’s a book written in trichromatic technicolour where the everyday is given a psychedelic edge (concrete places like Mount Vernon and Skegoneill Avenue become dreamscapes of flowing water) and the militarised elements of the world around the children simply fall into place (‘three green Saracens floated up the main road’). It will be published by Granta Book on the 3rd of August.

A warm welcome to the new Seamus Heaney International Visiting Poetry Fellow, Jane Hirshfield, pictured with Northern Irish novelist and poet, Nick Laird and Professor Glenn Patterson, Director of the @HeaneyCentre, at @QUBelfast last week. pic.twitter.com/jjNrNSamqf

— Arts Council of Northern Ireland (@ArtsCouncilNI) November 11, 2022

Leontia Flynn’s Taking Liberties is her fifth book of poems and makes clear what many people have known for the best part of two decades: she is one of the very best poets writing in Ireland in the twenty-first century. Taking Liberties is a consolidation of various strands of her poetic lives: musical without being conventional, funny without playing to the choir, scholarly without being exclusionary, dark without being morbid.

This is a book to return to: the poems found in it are crystalline lyrics where interior and exterior worlds collide: the book is full of private thoughts playing out in public spaces. In a nod to Dante, the poet writes: ‘near the wandering/ mid-point/ a reader re-finds her page/ in the story of life.’

Nick Laird’s Up Late, like Flynn’s Taking Liberties, is his fifth book of poems and finds his recalibrating old ground. In this book his voice has become more expansive, and in a literal sense Faber have extended their book format by an inch or so to accommodate his frequent long lines. The interconnected lyrics meditate on isolation, family life and the absurdities of global communication: ‘I’m registered dead/ but Alison in Belfast tells me/ I need the second and fifth/ letters of a password// I don’t remember having set.’

‘Cuttings,’ the opening poem of Nick Laird’s first book that I mentioned earlier features the poet’s ‘angry and beautiful father’ in a barber’s chair with ‘his head full of lather and unusual thoughts.’ The title poem, an elegy for the poet’s father (who died with Covid during a period of strict lockdown) is nothing short of a masterpiece. It gathers together all of Laird’s strengths (his rhythms, his tics of vocabulary and association, his eye for detail and acuity for knowing the right moment) and puts them to work in honour of his longest-standing subject. It could become one of the enduring works of the pandemic, in which there was a collective displacement of the conventions of grief. It does not have the appearance of something ‘recollected in tranquillity’, to borrow from Wordsworth, but instead shows all the rational and irrational confluences of grief playing out, seemingly, in real time.