ON August 13th 1958 it was publicly announced that the Belfast Corporation had finally agreed after discussions and proposals dating back to 1937, to take over responsibility for Shankill cemetery and its maintenance. It was decided to ‘transform it from a cemetery’ into a “quiet garden” with seating, spacious lawns and flower beds.

Tragically, this decision, in effect, ensured the eradication of the remaining historical Shankill burial ground; a site of indescribable historical and cultural significance, once containing as many as half a million interments. However, the story of neglect and preservation of this sacred place and the resplendent character of an ancient rural cemetery, went back much further.

Shankill Cemetery is believed to be the oldest cemetery in Belfast and once a burial ground for the earliest pastoral settlements of indigenous Irish people – the vast area and Gaelic Kingdom known as Dalaradia, of Down and Antrim. Part of this area later became the original settlement of the ‘town’ of Belfast that developed from the beginning of the 17th century following the Ulster Plantations of lowland Scots and English Presbyterian colonists by the English King James I.

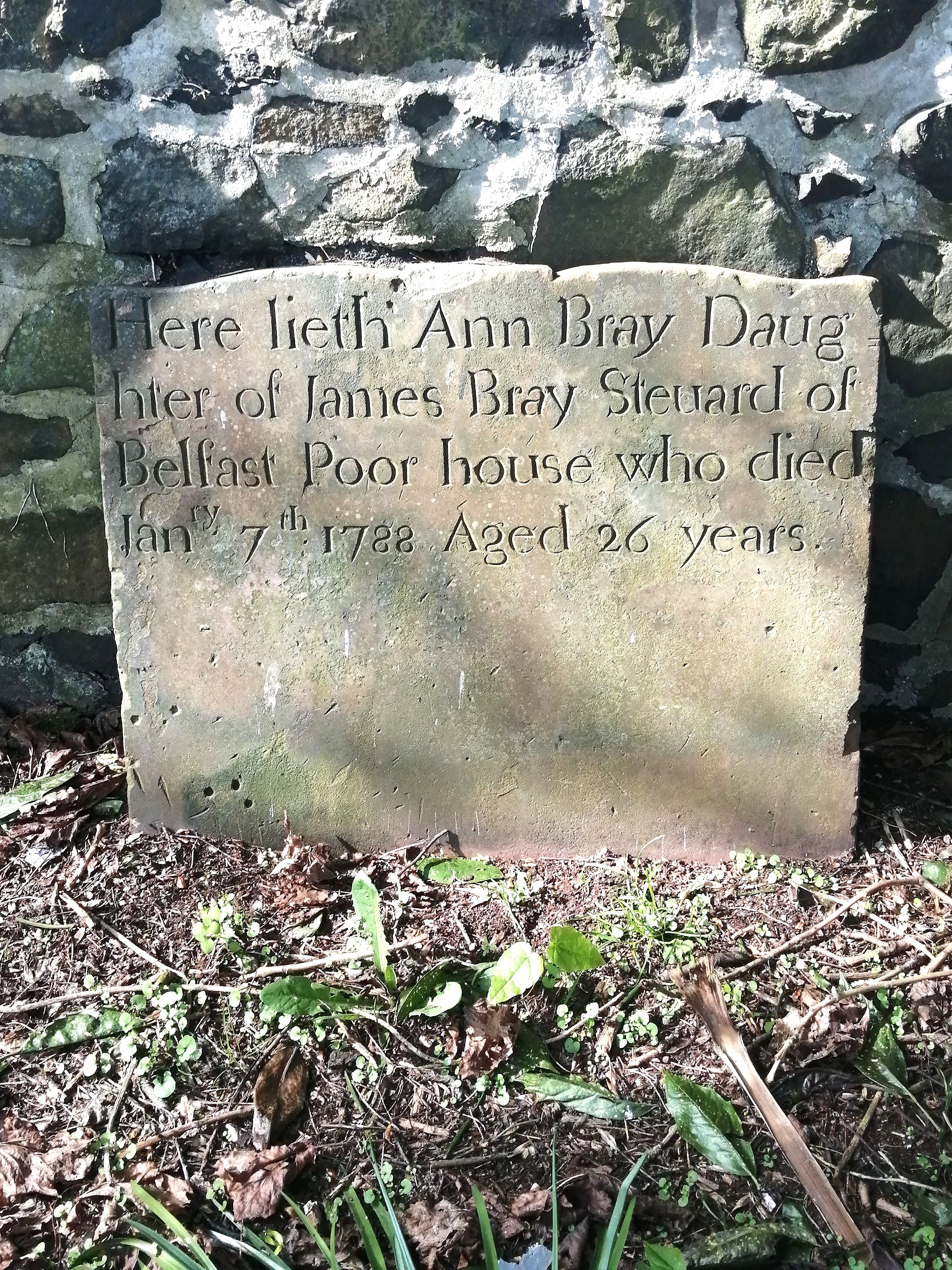

As a burial site it’s speculated as dating back 1500 years, although the oldest known headstone dates to 1685.The name Shankill, earlier spelt ‘Shank-hill’ comes from the Irish sean cill – old church. Historical accounts suggest the site may have had associations with St Patrick and that an old church and burial ground was established there in the 5th century AD. However, the earliest known record of a church there, dates from 1306 and known as the White Church, taking the name Shankill or ‘Old Church’ during the 16th century. A large ancient artifact – the ‘Bulluan Stone’, below, with a water font carved at its centre, recovered at the cemetery in 1855, now rests preserved since 1911 at nearby St Matthew's Chapel; possibly with connections to the original church or used for ceremonial rites in the pre-Christian era.

Sadly, an irresponsible act undermining the preservation of the cemetery’s history and records was revealed in the Belfast Telegraph in 1945. 'Parish Notes of the Past' in the Shankill (St Matthew's) Parish Magazine, Belfast — “In 1874 a deputation from the Select Vestry waited on the Sexton to get the books of the graveyard, who stated ‘he would not give up the books under a sum of £50.’ As the Select Vestry would not agree to this, ‘he burned the books.’ (There were almost 5,000 holders of burial rights.)”

Belfast historian, John Marshal, (Belfast Telegraph, 1932) passionately urged that the cemetery be cherished and preserved for its historical and cultural importance.

“The wayfarer passing along the Shankill Road and glancing at the wilderness of bushes, grass and weed-grown graves, with here and there headstones standing at all sorts of angles, could scarcely imagine that the prospect meeting his vision was Belfast’s oldest graveyard, with an antiquity of probably fifteen hundred years. The quiet dead reck not of their surroundings, but the living community of today have a duty not only to the resting place of their forbears, but also to their own self-respect, in seeing to it that the present discreditable condition of Shankill burial ground is remedied, and provision made for its efficient maintenance.”

The Enquiry by the Ministry of Home Affairs into the future of the Shankill Cemetery was conducted in Belfast on 19th October 1937 by Dr L.D. Graham, Medical Inspector. It related to the discontinuance of its use for burials following the request by the Church of Ireland, and reported by the Belfast Newsletter. It was in an extremely dilapidated state; the Church legal adviser revealed that, “…the burial ground was desecrated and damaged, and had become the resort of idle persons who went there to smoke, chatter, and horrible as it may seem, to play cards upon the very graves…It was horrible to see how many graves had been damaged and anything of value taken away. Railings had been removed from graves to be sold as scrap, headstones broken, trees sawn down for firewood, and wreathes wrenched from their cases.

Mr Chambers described the situation of the graveyard, crowded in by houses, schools, cinemas and shops, and stated that it had become more like a public playground than a sacred burial place. The children of the district had no other open space, and they could be seen playing hide and seek behind the tombstones, and using the railings of graves as bars for gymnastic exercises.”

Interestingly on October 4th 1935 the Select Vestry of the Church of Ireland had strongly advocated for Belfast Corporation to take over control and maintenance of the cemetery based on its history as a ‘non-denominational’ Christian burial ground.

“It is not fair that Shankill Graveyard should be lumped in with other grave yards in the city. For many hundreds of years Shankill has been the burial place for people of all denominations in what is now the city of Belfast and for a wide area outside of it; not five per cent of the present burials in Shankill are of actual parishioners of the present Shankill Parish, but those having burial rights in it live in all parts of the City of Belfast. This makes the claims of Shankill Graveyard on Belfast Corporation unique, and it is only reasonable that the Corporation be asked to assume responsibility for the graveyard.”

By the 1860s shortage of burial space remained acute and very serious public health problems emerged. After the years of the Great Famine, Belfast’s development and population growth were driven by rapidly accelerated industrialization, and maritime trade. The population grew dramatically – approximately 20,000 in 1800, to 100,000 by 1850, and 200,000 by 1876.

On October 17th 1863, the Town Improvement Committee presented their report to the Town Council, “On the Condition of Certain Burial Grounds in the Borough of Belfast.” It emphasized the urgent necessity of procuring a new Public Cemetery to cope with the need for burial space given the overcrowded and highly unsanitary state of the old burial grounds of the town. Subsequently the New Belfast City Cemetery on the Falls Road was formally opened on August 1st 1869 following the Town Council’s acceptance of the sanitary inquiry findings of Dr Knox, Poor Law Inspector’s report in 1867 on the state of Belfast’s burial grounds and the Town Improvement Committee’s report of 1863. A Privy Council Order was issued closing wholly or partially the three burial grounds of Belfast, Clifton Street, Friar’s Bush and Shankill; all three with some exceptions had substantially reached maximum capacity for further burials being seriously over crowded for years.

After the privy Council Order in July 1869 the most gruesome and shocking events occurred in the Shankill Cemetery. The Northern Whig’s report of August 3rd, 1869 is quoted in full:

“The order of the Privy Council… prohibits interments in any portion of the ground when a grave cannot be made seven feet in depth without the disturbance of human remains, and it is well known that in most of the “old ground in Shankill there is not on an average one foot of earth over the coffins and in some places, owing to the want of room, there are three or four coffins all interred within a few months. Some of those having friends or relatives buried in this manner were of opinion that they could evade the order of the Privy Council by raising the remains of their departed friends, re-digging the graves to a greater depth, and reinterring the bodies.

"On Saturday 31st July and Sunday...large bodies of men assembled in the graveyard, and, assisted by the gravedigger, commenced the task of exhumation, and on Sunday evening the graveyard presented a most horrible appearance—coffins, skulls, and bones of all descriptions lying about on almost every yard of the surface of the ground. We counted upwards of one hundred coffins thus rudely raised from the graves and human bones were scattered about in heaps in everywhere. The smell was so sickening that parties could hardly approach the grounds…

"Several members of the public attempted to dissuade the gravediggers to cease their work, but to no avail and the exhumations continued in earnest. By Sunday night, a great number of the coffins and bodies had been reinterred, but many of them lay on the ground till yesterday morning, when fresh batches of men arrived to raise more bodies and continue the ghastly sickening work. Yesterday morning, seventy-nine coffins of all sizes and in all stages of decay, from a week to several years, were tossed about on the top of the ground, and heaps of skulls and bones were pitched promiscuously in every corner of the yard awaiting re-interment. Up to yesterday morning this work was carried on without hindrance, and large numbers of men arrived with spades, pickaxes, crowbars, shovels, barrows, and commenced afresh to dig up the earth…

"The mayor, and other officials supported by a large number of the police arrived and told the large number of men present digging up the graves to cease the illegal activity or bear the consequences; the coffins reburied and the graves were to be backfilled and the ground to be closed.

"At this time about 200 graves had been opened, and a most disgusting sight presented, one barely conceivable to a Christian country...Hundreds of coffins were huddled together, or lying a foot or two apart and heaps of human remains were scattered about only newly brought to the surface. Those who were digging at the graves had bottles of whiskey or brandy beside them, in order to enable them to perform their unnatural work.

"…Men and women burst into tears on seeing the graves of their friends opened up to the public view by the parties who were digging up the adjacent earth. People lay down weeping on the graves of their relatives in order to prevent the diggers touching them with their spades. Others ran off for their friends, who came and “stood guard” in different parts of the yard to prevent intrusion on the last resting places of their relatives.”

Such was the gruesome history and disrespect for the interred of the Shankill Cemetery as ‘a final resting place’ of solemnity and dignity.

Nowadays its utility finds itself for the Greater Shankill community as a ‘quiet garden’ for rest and recreation. Its history is presented by local tour guides, at times within a somewhat contrived historical framework – emphasizing the cemetery as a final resting place for war veterans who fought in the British imperialist wars as well as veterans of the two world wars. Homage is paid to British imperialism, symbolized by a large statue of Queen Victoria situated prominently and strategically in a direct line to its front entrance gates. This sculpture was never part of the historical Shankill cemetery, having been relocated there from its original location in Durham Street, Belfast, in 2003. Former Belfast Lord Mayor Hugh Smyth (PUP), was instrumental in the campaign to have the statue placed there.

Shankill Cemetery is not a ‘war graves’ cemetery but war veterans are interred there and honoured. Its ancient origins were as a final resting place for a rural community. As expressed by John Marshall in 1932, “Shankill graveyard has held the ashes of the parishioners from the dawn of Christianity, when the creaght (herdsmen) tended his cattle on the slopes of Divis, and the scullog (farmer), with the rude implements of the time, tilled his plots, where now stand the habitations of Peter’s Hill, or the winding ways of Woodvale Park…”

In modern centuries it was a town/city burial ground, largely the final resting place of the poorest and hardest-working people – not least thousands of ‘linen mill slaves’ – “the helpless slaves of soulless employers” of industrialized Belfast, of vast numbers housed in hideous conditions who died prematurely of preventable disease and illness. Here it was that thousands of victims of the Great Irish Famine and the typhus and cholera epidemics were abhorrently cast into ‘mass graves’ in 1847, to remain unmarked, anonymous and unknown, after British officialdom effectively left the problem to be resolved locally by the people of Belfast in whatever manner they saw fit.

The Corporation stated in 1958, “The whole emphasis of the new scheme will be on ‘preservation.’ Though some headstones will be removed, the more historic will be placed along the boundary walls.” Sadly ‘preservation’ was lost in the list of priorities and today it is virtually impossible to even conceive of the site as the ‘Shankill Cemetery’ of old; a fraction of the historical cemetery exists. However, finally in 2013, a locally commissioned, innovative and inspired memorial stone was unveiled at Shankill Cemetery containing images reflecting the many facets of its long history.

HA Mac Cartan, (The Glamour of Belfast,1921) provided the perfect epitaph for the Shankill Cemetery.

“For this 'Old Church' which gave Shankill its name was once…a thing of beauty as well as sanctity. Before it became the 'Old Church' it was the 'White Church', visited by Gaelic chieftains as well as by John De Courcy himself…given much to prayer in the intervals of battle. Do their ghosts haunt the congested old graveyard where the Church once stood? What would be your feelings, bustling citizens, if on a night of yellow moonlight your eyes should be tranced by the vision of a grave-faced chieftain of the O’ Neills in cloak and kirtle entering a mystic Church, with John De Courcy, free of battle-axe and armour, walking peacefully by his side.”

©Brendan Muldoon, 2022