When an insurance salesman for Prudential passed Laurel Hill, a volcanic outcrop in New Jersey, in a train in the 1890s, he hit on the idea of a slogan: ‘Get a Piece of the Rock.’

Later, the advertising agency added the slogan ‘The Prudential has the Strength of Gibraltar’ and in 1989, almost a century later, the Prudential simplified the link by adopting a pictogram of the Rock of Gibraltar with a new font and image with which the American Insurance Co has been associated ever since.

In 1704, Anglo-Dutch forces captured Gibraltar but it was ceded to Great Britain in perpetuity under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. For more than 3½ years, from June 1779 to February 1783, the tiny territory of Gibraltar was besieged and blockaded, on land and at sea, by the overwhelming forces of Spain and France. It became the longest siege in British history, and Gibraltar became the most famous fortress in the world. The 240th anniversary of the start of the siege was marked in 2019. The British government’s obsession with saving Gibraltar was blamed for the loss of America in the War of Independence.

During World War II it was an important base for the Royal Navy as it controlled the entrance and exit to the Mediterranean Sea, the Strait of Gibraltar, which is only nine miles wide at this naval choke point. It remains strategically important, with half the world's seaborne trade passing through the strait.

The sovereignty of Gibraltar has long been a point of contention in Anglo-Spanish relations because Spain asserts a claim to the territory. Every Spanish government, whether republican or monarchist, sees Gibraltar as a tantalising temptation. General Franco coveted the prize but stopped short of using force to achieve it. Part of the reason for this are the miles of underground tunnels and armed galleries deep throughout the underground base giving more credence to the term – as solid as the Rock of Gibraltar.

However, among the history files stored in Madrid is a daring plan for a raid on the territory to be carried out by Irish commandos, aimed at seizing the colony and handing it over to Spain.

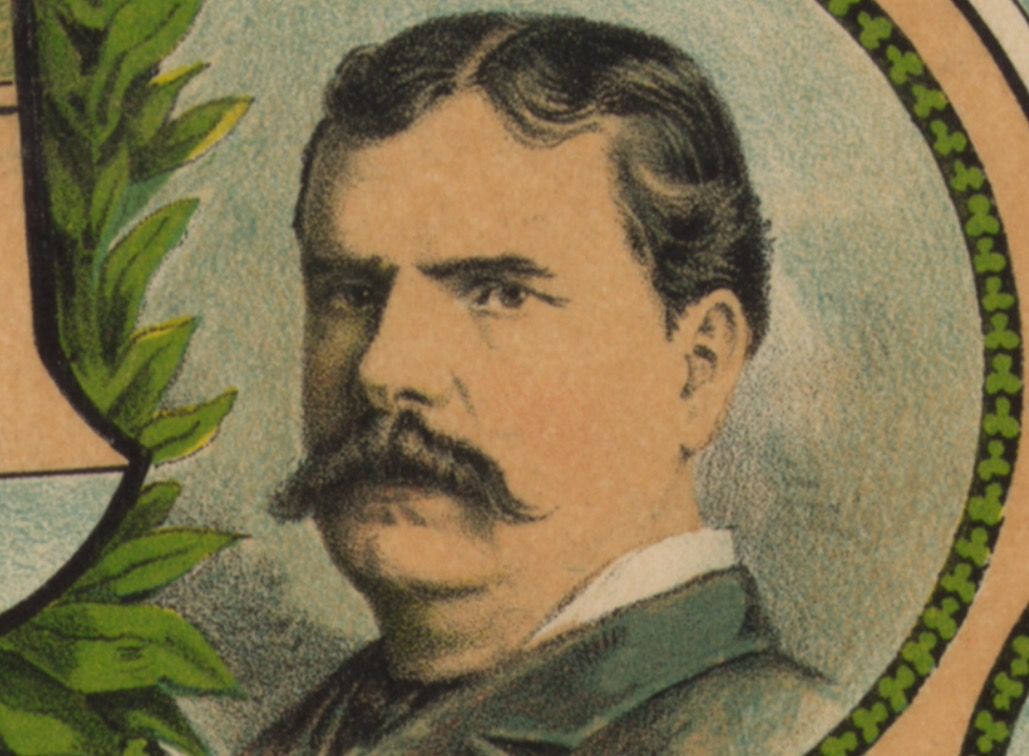

The man responsible for the plan was Senor Blake, better known in Ireland, England, Cuba, France, Mexico and America as James J. O’Kelly.

When his father died in 1861, James, aged 15, moved from his home in Dublin to London to train as a sculptor in his uncle’s studio. In 1863, he decamped to Paris, where he studied law for a short time before joining the Foreign Legion, thus following in the footsteps of his friend John Devoy, who had enrolled two years earlier. Devoy would become head of Clan na Gael in America.

After a period in Algeria, O’Kelly fought in Napoleon III’s disastrous expedition to install the Austrian Prince Maximilian as Emperor of Mexico. O’Kelly deserted and, despite being captured by Mexican guerrillas, made it to the United States. In the late 1860s, O’Kelly was appointed secretary to the ultra-secret Supreme Council of the IRB and became a leading arms agent for the movement in Britain.

He was the only member of the Supreme Council who was a trained soldier. On arriving in Ireland he saw that the IRB was ill-equipped for a rising and opposed the idea. Returning to London in 1868 he became London correspondent of The Irishman and the leading IRB arms agent in Britain. In February 1871 O’Kelly went to America and was employed as art editor and drama critic of the New York Herald. Shortly afterwards he became the paper’s war correspondent and in 1873 secured an exclusive interview with Cuban guerrillas who were fighting for independence. After advising the rebels on military matters, he was arrested by the Spanish-Cuban army and sentenced to death.

The president of the Spanish Republic intervened on his behalf and he was brought to Spain where he was paroled. In 1874 he was tipped off that he was to be rearrested and he crossed over into Gibraltar. Posing as Senor Blake, a tourist, he strolled around the garrison and worked out a scheme to attack it.

Spain became a monarchy again later that year and he was able to return there. He began to lobby ministers of King Alphonso about the possibility of annexing The Plantation, as he called Gibraltar.

In America O’Donovan Rossa proposed that parties of “skirmishers” should be set up and sent abroad to hit English nerve centres in other parts of the world. “England will not know where or how she is to be struck,” wrote Rossa, calling for 5,000 dollars to open the fund. Despite opposition from many within the movement the Skirmishing Fund was an instant success and by 1881 over 90,000 dollars had been collected.

John Devoy received correspondence from O’Kelly in Madrid detailing his plan to conquer Gibraltar. The Rock was to be taken in a lightning midnight raid. The IRB was to provide the Irish contingent and Clan na nGael was to send US Army veterans to seize the installations. Spanish troops would then take over when the coup was complete.

A leading member of Clan na Gael, Dr William Carroll, a Presbyterian from Donegal, joined O’Kelly in 1878 to negotiate with the Spanish government, but Prime Minister Canovas del Castillo, while admitting that the plan was technically perfect, decided against the attack because Spain could not match the naval power of England.

O’Kelly became disillusioned and eventually joined Parnell’s parliamentary party, becoming MP for North Roscommon in 1880.

Meanwhile, the Skirmishing Fund was used in a different way. The money financed John P. Holland in his submarine research and paid for the building of three prototypes. The intention was to use the submarine whenever the opportunity arose – either to use it independently or to offer it to any power fighting England.

Finally it was the US government which benefited by taking over the invention when it was almost perfected. The first American submarine, the Holland, was launched in 1898 as a result of Fenian-inspired research. It speaks much of the vision of the Fenian leadership who spent over 60,000 dollars on the submarine programme at a time when few governments saw any value in the research.

Gibraltar is now safe from the types of attack that Senor Blake had envisaged, but leaders such as General Franco must have wished that he had been given support.