IT happens every time. You watch the build-up to the US Presidential election and you wish you knew exactly what was going on. You tune in to the election night specials and you wonder why after all these years the whole thing remains a mystery to you.

Well, the confusion stops here. In this handy explainer to US Presidential elections, you'll learn everything you need to know about what's happening now across the United States – and what's going to happen on November 5.

About time too.

FOUR MORE YEARS

THE governing term of a US President is relatively short at four years (it’s five in Ireland and Britain), but it’s effectively even shorter than that.

BACK IN BLACK: Donald Trump is seeking to win after refusing to acknowledge he lost

The term begins to seem positively fleeting when we consider that the complex and hugely time-consuming and resource-demanding process of selecting Presidential candidates takes place in the year leading up to the Presidential election in November.

HERE WE GO AGAIN

Across the final year of a Presidential term, a raft of Presidential candidates is nominated by mean of ‘primaries’ and ‘caucuses’ – terms you’ll have heard of but perhaps never really understood. That’s not surprising because the system is a distinctly random and eccentric process that is not codified in election law.

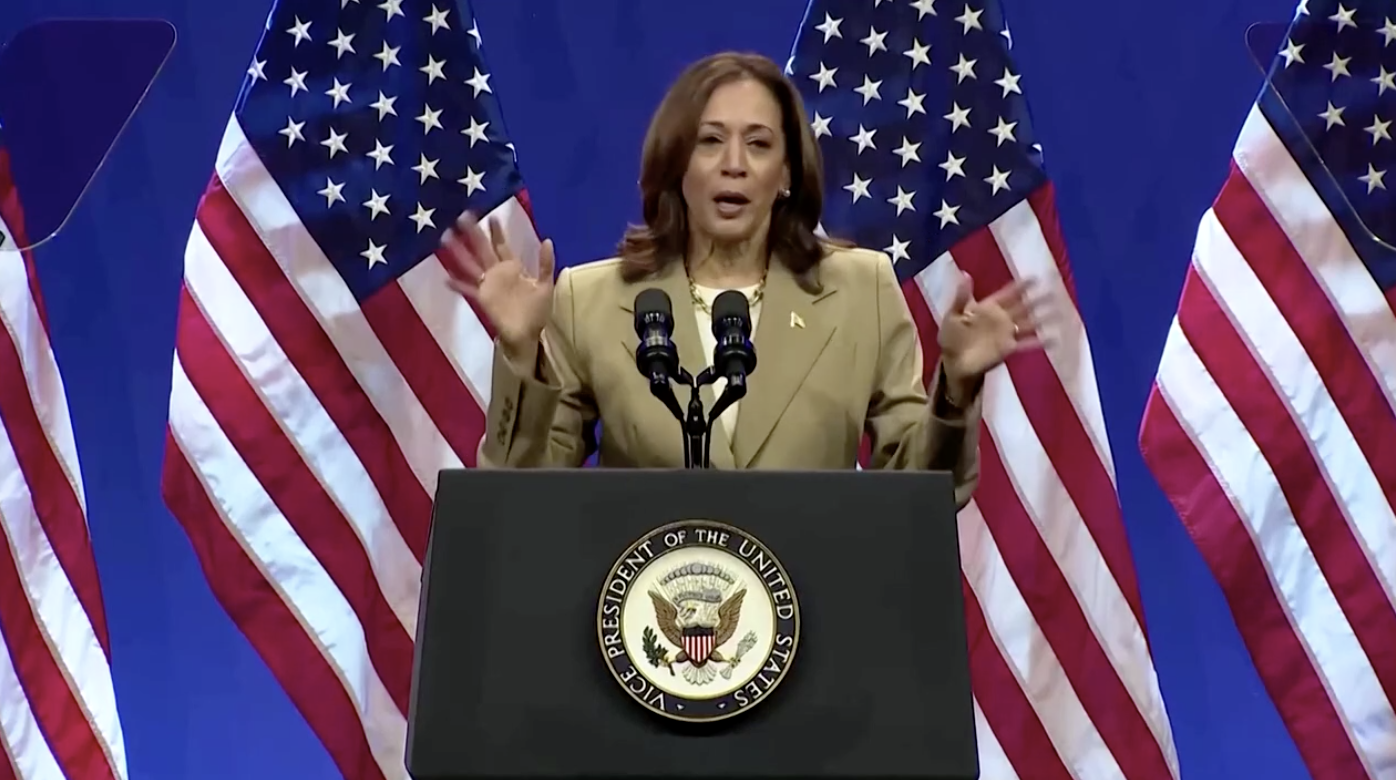

DECISION TIME: A caucus is a very public and often noisy affair

Most states hold primaries; an ever-dwindling number hold caucuses; some states hold both; some states hold a hybrid of both.

Whatever the process, no vote is held for a named candidate. Rather, the primaries and caucuses determine the number of delegates (or supporters) each candidate will be represented by when the time comes for a single candidate to emerge from the final selection process. It’s a complex system, but for the purposes of this explainer we'll keep it simple.

PRIMARIES

Primaries are run by state and local governments, with delegates selected by the kind of standard secret ballot we would recognise. But within that more traditional system, practice varies from state to state. Some states require attendees to be registered members of the party holding the primary; other states allow anyone to attend, whether they’re registered to a party or not.

CAUCUSES

Caucuses, meanwhile, are organised by political parties, with supporters of candidates dividing themselves openly and often noisily into groups, the biggest and strongest of which go forward to the final phase – the summer National Conventions. There might no longer be the brass bands, cigars and hats being thrown in the air like you’ve seen in the movies, but the caucuses are still pretty lively events.

NATIONAL CONVENTIONS

Right. So the delegates have been selected from the primaries and caucuses with a brief to represent their Presidential candidate. They then head off in the summer to press the case for their guy or gal in the showpiece National Conventions.

UNCHANGED: The 1884 Republican National Convention in Chicago – the basic system remains the same

This is the final step in the selection of the person each party is going to put forward as their candidate to stand for election for President of the United States.

After an intense four days of endorsing, lobbying and tallying, each party will – with huge fanfare and fuss – announce the candidate who will run for President in November (and of course their running mate).

HERE COMES NOVEMBER

Get this: Americans don’t vote for their President.

Well... not directly anyway.

On the day of the election in November, they vote to appoint 538 ‘electors’ – members of the ‘Electoral College’. That’s another term you’ll have heard, but might not have fully understood. It's another of the strange ways that the US electoral system has of separating a vote from a candidate.

EXERCISING THE FRANCHISE: A queue – sorry, line – of Americans waiting to vote

Each state is allocated a number of Electoral College members roughly corresponding to the state’s size and its number of members of Congress. The aim of a Presidential candidate on election day is to obtain a simple majority of 270 of the 538 Electoral College votes.

Electors are generally prominent figures in state politics but little-known nationally. In the weeks after the November election (mostly in December), the electors will return to their states and go through the entirely mechanical and predictable act of casting their votes for their party’s candidate for President. It's why there's quite a lengthy gap between the early-November election and the late-January inauguration of the winner.

THE WINNING LOSER

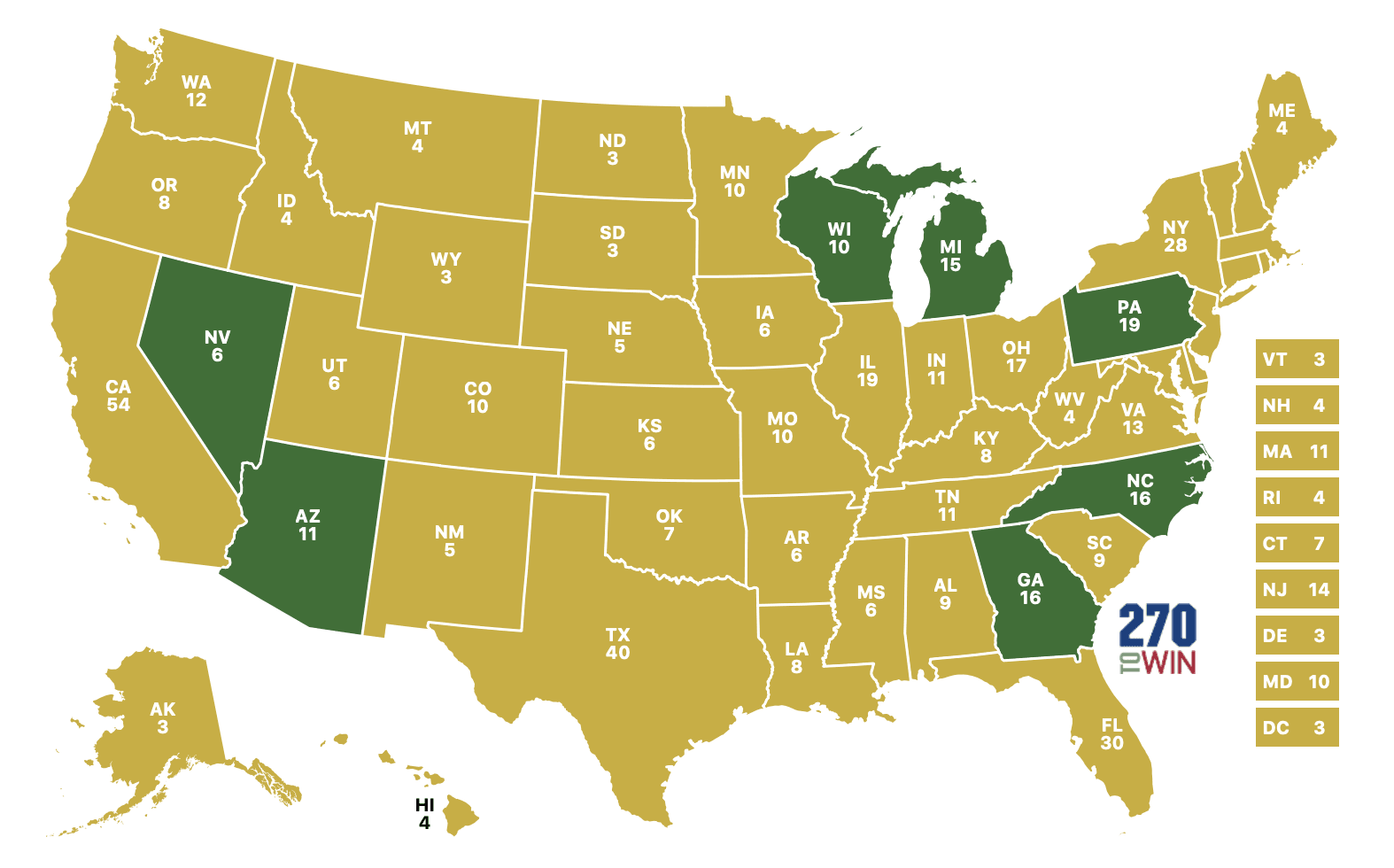

Perhaps the single most eccentric aspect of the United States’ odd and unique electoral system is that in what's essentially a first past the post contest the winner can lose. That is to say, the candidate who has the most votes cast in their favour (the ‘popular vote’) can be beaten by the candidate who secures the magic number of 270 Electoral College votes. (The number of Electoral College votes per state can be seen below.)

STATE OF PLAY: The 2024 Electoral College elector count map

This quirk of the winner 'losing' is explained by the ‘winner takes all’ nature of the election, which rules that the candidate who comes out top in any single state takes ALL of that state’s Electoral College votes. Take Florida, for example, with 30 electors. If a candidate claims 20 of those 30 Electoral College electors, all 30 go to that candidate's election tally.

The Electoral College triumphing over the popular vote is rare – it has happened only five times in US history. But it did take place as recently as 2016 when Hillary Clinton secured around three million votes more than Donald Trump.

BATTLING IT OUT

‘Battleground’ or ‘swing’ states are the beating heart of the US Presidential election and claim an extraordinary degree of attention from candidates. These are the relatively small number of states which are too close to call. In fact, it can reasonably be argued that swing states ARE the election.

With the other states more or less in the bag (with EVERY Electoral College vote, remember), parties pour an immense amount of resources into the battleground states because they are at the very tipping end of the electoral see-saw. Fully 75 per cent of the candidates’ time has been historically spent in battleground states.

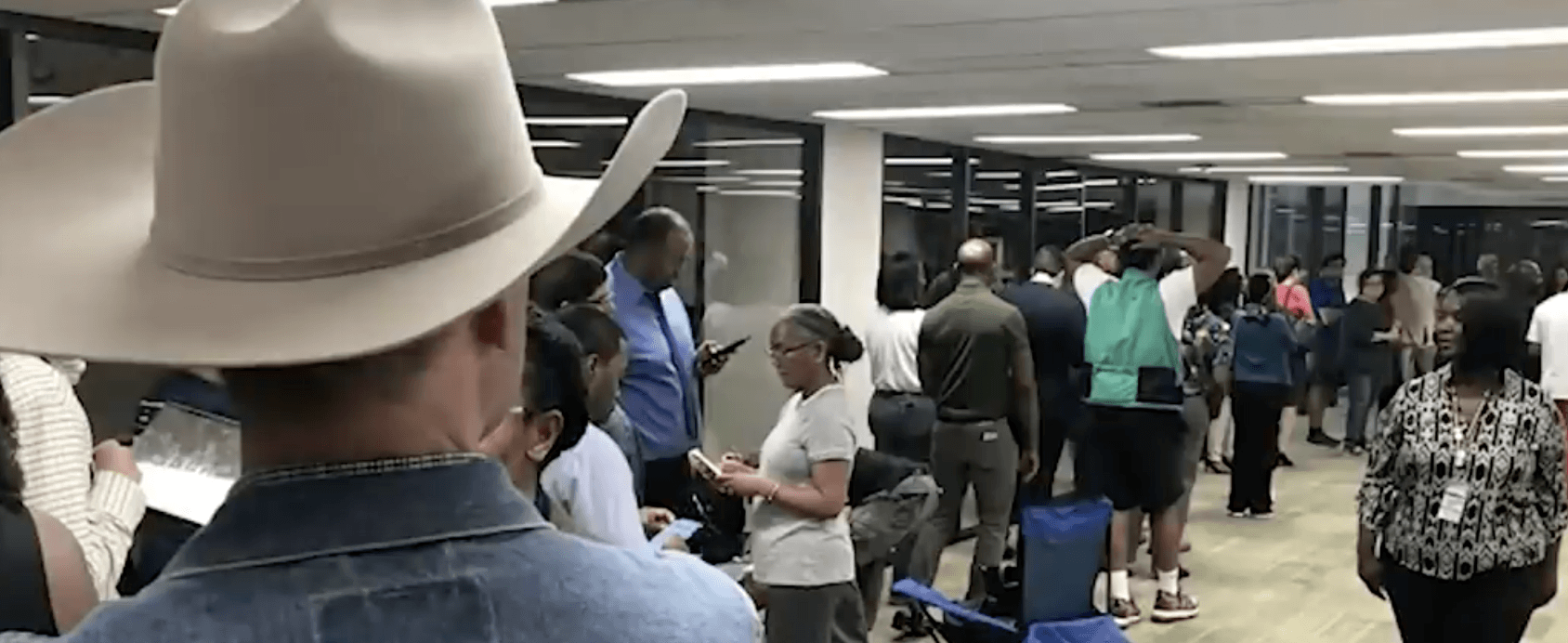

GEORGIA ON MY MIND: The Peach State is one of six battleground election contests

Of course, traditional Republican or Democrat states can change allegiance over time and so states can either become swing states or stop being swing states. To take Florida again as an example, it was for a long time the ultimate swing state, but is now considered reliably Republican. Despite the changes, the number of battleground states is always small and the focus on them always intense.

There are seven states which will this year effectively elect the President of the United States: Arizona; Georgia; Michigan; Nevada; North Carolina; Pennsylvania; Wisconsin. And just as the campaign teams fixate on these states right up to the final day of campaigning, so will the media covering the election on Tuesday, November 5.

CALLING IT OUT

There is no centralised official tallying system in the US and none of the traditional winner announcements that we're used to. And so the large media outlets have become the means by which Americans – and the world – learn how the states, and thus the country, have voted.

The intense focus of the campaigns on the swing states will on election night switch to an intense focus on how the big news networks and news agencies ‘call’ the results in swing states – and eventually call the President of the United States.

MUST-WATCH: The networks take their election night result calls very seriously

The calling of states – and the election – by the likes of the Press Association (PA), CNN, CBS, MSNBC and Fox is a major test of prestige and credibility for the networks and press agencies. Think of it as a journalistic Super Bowl.

They pour massive resources into putting staff on the ground to analyse local results from which they project wider state and national outcomes. For instance, PA – considered the gold standard in Presidential election calls – will this November 5 have an incredible 4,000 local stringers on duty, supplying a constant stream of data from around the US from which analysts at HQ determine their calls.

OLD SCHOOL

As we’ve seen, the US electoral system is extremely convoluted – many of its central processes have remained unchanged since the 19th century.

The incredibly disruptive entrance of Donald Trump into US electoral politics in 2016 has sent shockwaves through that system, particularly his refusal to accept the 2020 result, which resulted in a deadly attempted coup at the very seat of government. The hugely complex nature of the voting system means that an orderly handover of power is entirely dependent on the losing candidate's goodwill – something that wasn't forthcoming in 2020, triggering a national crisis from which the United States is still reeling.

DEADLY: The post-election violence of January 6, 2021, may be a catalyst for change

A long-overdue overhaul of this creaking old system is coming. Whether those changes will be democratically enacted in a post-Trump United States, or whether they’ll be ruthlessly imposed in the second-term dictatorship that Trump has promised, only November will tell.