THE period from around 1800 to 1830 in Ireland and in Britain was the era of the ‘Resurrectionists’, also known as ‘Sackem-ups’ or more familiarly, ‘Body Snatchers’. Graveyards were stalked at the ‘dead of night’ by gangs of body snatchers determined to exhume freshly interred corpses, to be sold on to anatomists and medical schools for dissection and study.

In those years there was a serious shortage of corpses for anatomical study as the source of bodies for dissection were mainly those of executed criminals. The UK Judgment of Death Act of 1823 saw the number of crimes punishable by death in Britain drop dramatically; (Consequently the supply of dead bodies of executed criminals was diminished. In this way the lucrative ‘resurrectionists movement’ emerged and thrived by supplying the short fall in dead bodies, which could fetch as much as ten to twelve guineas per ‘subject’.

The Belfast Telegraph, March 2 1910 suggested there were many highly organised body snatching gangs, often contracted in effect by anatomists, with payment of a ‘retaining fee’ at the opening of the season, ‘finishing money’ at its close and a payment for each body. For small bodies of children – less than three feet, so much per inch was paid. If the person was caught the medical staff provided payments to the families and a gratuity to the body snatcher upon release. The articles states, receipts for the year 1810/11 for one resurrectionist were found to be 1,328 guineas for body-snatching, exclusive of smalls (children) and teeth. Teeth and long hair were often removed from bodies and sold separately to wig makers and dentists to make rudimentary false teeth applications for well to do clients. The trade in teeth and hair from cadavers was a lucrative sideline for the resurrectionists.

Body snatchers would frequently steal away in one night eight -10 corpses, and reports from numerous resurrectionists’ diaries show that in some instances as many as 15 bodies were exhumed in one night in London’s cemeteries.

Anatomy lecturers likely asked little in the way of questions about where the welcome supply of bodies were coming from, other than wanting for convenience to accept that they were down and outs without family or friends, ‘unknowns’ having died of ‘natural causes’, destitution etc. A prevalent feeling within the medical profession was that if anatomy schools and medical science were to advance and medical students properly trained, then body snatching was a necessary evil.

Brendan Muldoon (author) holding Night Watchman's Musket used to ward of Body Snatchers, 1830. With kind permission of Archive & Heritage Coordinator, Clifton House Heritage Centre

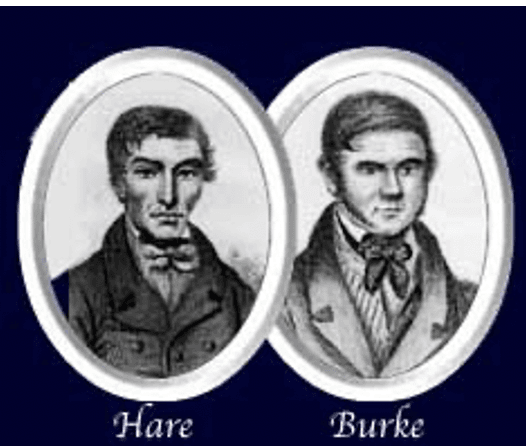

With medical schools the ‘fresher’ the body the more money it was worth, thus it didn’t take long before grave-robbing graduated to ‘anatomy murder’ i.e. murder committed with the sole intention of providing the remains for medical research and attracting a generous monetary reward. The two most infamous partners in crime in anatomy murder were two Irishmen William Burke and William Hare, based in Edinburgh. They met and became close friends when Burke moved with his mistress Helen McDougal to lodgings in Tanner’s Close in Edinburgh, which Hare was running as a boarding house with Margaret Laird, a widower with whom he lived.

Their first dealing in the sale of bodies happened in December 1827 when one of Hare’s tenants, an elderly pensioner named Donald died of natural causes whilst still owing £4.00 in rent. To cover the man’s debt the pair weighted his coffin down prior to his funeral and took his body to the medical school at Edinburgh University. Number 10 Surgeons Square was the infamous address to which Burke and Hare delivered their bodies to the porters for the notorious Dr Knox and were paid seven pounds and ten shillings for the body.

After this the pair decided to entice victims to the lodging house, preying on Edinburgh’s poorest communities who were less likely to be missed or recognized, including downs and outs and prostitutes among others. Helped by their female companions they would ply them with drink until unconscious, then suffocate them – one held the nostrils and mouth closed as the other placed his full body weight across their rib cage to stop their breathing.

Burke and Hare murdered at least 16 people, likely many more. Their method of killing became known as ‘Burking’. Burke and Hare were arrested in 1828 along with their two female associates. Hare turned King’s evidence, he and his wife granted immunity from prosecution. On Christmas Day Burke was sentenced to death for the murder of Mary Docherty. Helen McDougal walked free. The judge stated. “I am disposed to agree that your sentence shall be put into execution in the usual way, that your body should be publicly dissected and anatomised; and I trust that if ever it is customary to preserve skeletons yours will be preserved in order that posterity may keep in remembrance your atrocious crimes.”

After execution Burke’s body was placed on public display and viewed by over 25,000 members of the public, before the private dissection was completed for the medical students. His skeleton still remains on exhibition in the anatomy museum at the Edinburgh University.

Belfast’s Northern Whig said of ‘Burking’ in December 1831: “Murder under any of its guises is horrible, but what name shall we find to characterize the revolting odiousness of this slaughtering of human animals for the market? Only think of a monster, bearing the lineaments of a man, inveigling a fellow being into the recesses of his den, and there deliberately slaying him with a view to the sale of his flesh.”

Glasgow, Edinburgh, and London were notorious centres of activity for the body snatching fraternity but various towns and counties in Ireland were well-known ‘haunts’ for the nocturnal activities of the body snatchers including Belfast and Dublin. Remote County Antrim cemeteries had serious problems with the activities of the resurrectionists and very many graves were plundered. On December 5 1831, The Northern Whig stated of Belfast and its surrounding counties –“Every graveyard in this part of Ireland within the range of the steam-boats is beset, nightly, by a set of savage and determined resurrectionists. We are firmly convinced that a very extensive trade in dead bodies is at present carrying on with Glasgow.

According to the Ballymena Weekly Telegraph, October 1941, the ‘Connor Body Boys’ were said to be one of the most daring and unscrupulous of the body snatching gangs, based around Co Antrim near the villages of Kells and Connor near Ballymena. One of their favoured cemeteries for body snatching was St Saviours and relatives held night vigils in St Saviour’s church graveyard where a stone ‘corpse house’ had been constructed to protect coffins from plundering, and were often armed with pistols should the Connor Body Boys arrive in the dead of night.

In Belfast numerous corpses were taken by the ghoulish body snatchers from the Clifton Street ‘New’ Burying Ground and the Friar’s Bush and Shankhill graveyards. The methods used by body snatchers usually didn’t involve digging up a whole area of ground above a grave until reaching a coffin. The easier way was to dig a straight shaft down behind the coffin to where the head would be facing, smash open the back of the coffin and slip a rope around the neck of the corpse and drag it out and up vertically to the surface in the most gruesome fashion.

Bodies were often exported by ship from Belfast or Dublin to England and Scotland in barrels or in large chests. Body snatching was punishable by stiff fines and or imprisonment, but the bottom line was that it was lucrative business in those days and worth the risk.

Medical students actively engaged in bodying snatching and supplying cadavers to anatomy schools and even used body parts for private dissection and study at their own lodgings. The following article appeared in Belfast’s Northern Whig, November 28 1831: "Some very shameful scenes, connected with the exhumation of dead bodies are now taking place in Belfast. On Friday last, a box, (believed to be the property of a certain medical student who was on his passage to Glasgow) about to be put on a steam boat at our quay, was suspected of containing a corpse: and, on being opened, a dead body was found therein, the student fled; or the incensed crowd would have taken summary vengeance on him.

“On Saturday, a skeleton of a human being, evidently not long from the knife of the anatomist, was discovered in one of the fields south of the White Linen Hall lying quite exposed on the green sward. An action like this is most disgraceful to any member of the medical profession, and such unfeeling exposure of the mangled remains of a human being is of itself sufficient to create the prejudice against raising subjects for dissections. No doubt, some brutal young student, belonging to Belfast, was guilty of this shameful conduct.”

During those years many desperate measures were resorted to ward of the grave-robbers. In most cemeteries families frequently held all night vigils to prevent the graves of their loved ones from being plundered, sometimes armed with pistols or cudgels. Family ‘vaults’ were also used to inter relatives. In Dublin a series of high walls and watch towers were constructed around Glasnevin cemetery in the early 1830s to guard against body snatchers. In rural cemeteries around Ireland heavily fortified stone structures known as ‘corpse-houses’ were constructed to place and protect up to three coffins at a time, allowing sufficient time for decomposition before they were removed and interred with all usual solemnities.

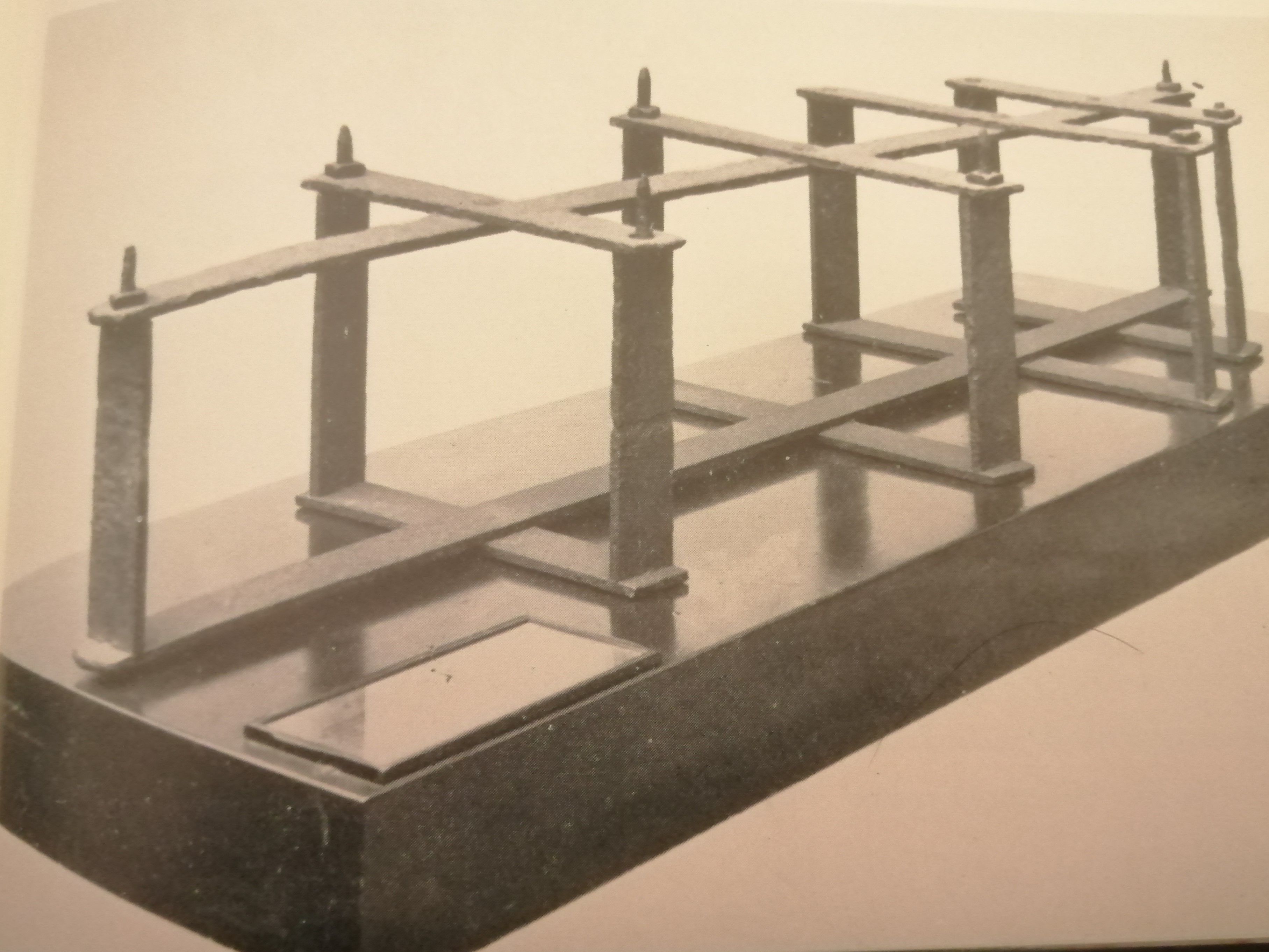

Mort-safe coffin cage used at Clifton St Cemetery

Precautions at Glasnevin were not always sufficient as a deterrent and one account related in the Belfast Evening Telegraph of March, 1910, was of a major confrontation between armed watchmen and a large contingent of body snatchers angry at having had their nefarious activities thwarted the previous Saturday night. Both groups were well armed with at least 60 muskets rounds fired and one man injured in the shoot-out. “The Church-bells were rung – men, almost naked, rushed from their beds, and a wild scene ensued.”

‘Mort-safes’– metal cages were also used to enclose coffins at burial for protection against body snatchers, as were iron coffins. At Clifton Street Graveyard in the early 1800s, families hired their own night-watchmen. Later the Clifton Street Poor House hired its own watchmen who were allowed to be armed for a brief period. The musket used by the night-watchmen is still on display in Clifton House Boardroom to this day. A stone watchtower was built at the Shankill cemetery for use by night-watch men to ward of body snatchers and some crumbling ruins there remain of it.

Even these methods could not foil the most outrageous and audacious raids during wakes and open raids are recorded for the theft of bodies during wakes, The Northern Whig, December 29 1831, reported, ‘Atrocious Outrage by Body Snatchers’.

“About six o’ clock on Friday evening a party of resurrectionists rushed into a house in Digges’s Lane, in which, in an upper apartment lay the corpse of a female in the name of Carrol, in the act of being waked; they immediately proceeded up to the room, where bearing down all opposition, and utterly reckless of the feelings of the friends and relatives of the dead, as to all sense of decency, they tore down the body from the board on which it was stretched, and dragged it perfectly naked downstairs into the lane, from thence to Glover’s Alley and finally succeeded in carrying it off.”

After the Burke and Hare saga times changed and it was to mark the beginning of the end for the ‘resurrectionist movement. The 1832 Anatomy Act ensured a plentiful supply of corpses became available for dissection and put an end to the ‘secret supply’ of bodies of anatomical schools in Britain and Ireland; licences were required for the practice of dissection, relatives could legally sell relatives bodies, whilst people could sell off their own body for dissection after death. Later those who went unclaimed having died in the Workhouse or unknown deceased paupers, or suicides, could all be donated to the Schools of Anatomy.

The Falkirk Herald of May 11 1887 stated that the activities of the resurrectionist movement continued to prevail until, “...the terrible crimes of Burke and Hare, which grew out of and formed the awful crisis of that system, were revealed, sending a thrill of horror through the civilized world.”

Brendan Muldoon © 2021