FÉILE an Phobail was formed in 1988, following the harrowing events of March that year when the killing of corporals Derek Wood and David Howes – at the funeral of IRA Volunteer Caoimhín Mac Brádaigh – led to West Belfast being branded a “terrorist community”.

To combat that narrative, a group of people including Gerry Adams, Danny Morrison and Siobhán O’Hanlon set out to establish a community festival that would combat this negative portrayal of the area.

Danny Morrison at Féile launch

Today, that festival has grown to become Ireland’s largest community festival. Discussing the formation of the festival this week, Danny Morrison began by congratulating the Andersonstown News on reaching the 50-year milestone.

“I remember when it first came out in 1972 and I was interned. When we received that Christmas edition of the Andersonstown News and all of our names were printed in it – I have to say it was a morale booster for the people, to have a community paper, which was probably one of the first community papers in Ireland.

Kneecap sing Guilty Conscience to 10,000 fans at the Falls Park in West Belfast.

— Féile an Phobail (@FeileBelfast) August 12, 2022

What a group! What a Féile! pic.twitter.com/tKeCXguuUB

“You had the established papers like the Ulster Herald, the Mourne Observer, the mainstream Irish News, but to have a community paper like the Andersonstown News was a forerunner of Féile an Phobail.”

Discussing how the people of West Belfast responded to comments such as being described as a “terrorist community”, Danny described West Belfast a half-century ago as a “vanquished community”.

“If you go back to the early 60s, we were a vanquished community. We were defeated. The Orange Order marched on the Falls Road right up until 1964. Even in 1969 when I worked as a barman in the Whitefort Inn, Orangemen coming from the Field crossed over the Andersonstown Road, came into the Whitefort for a pint before heading back to the Shankill.

“All of that changed with the rise of the Civil Rights Movement, People’s Democracy and the response of the unionist government to that. “The pogroms of 1969 was the root cause of the conflict.

The community then fought back against the state oppression. Things had been changing and while Féile an Phobail had been formally established in 1988, there had been small festivals in the like of Lenadoon and Andersonstown but these never lasted more than a few years then burnt out.

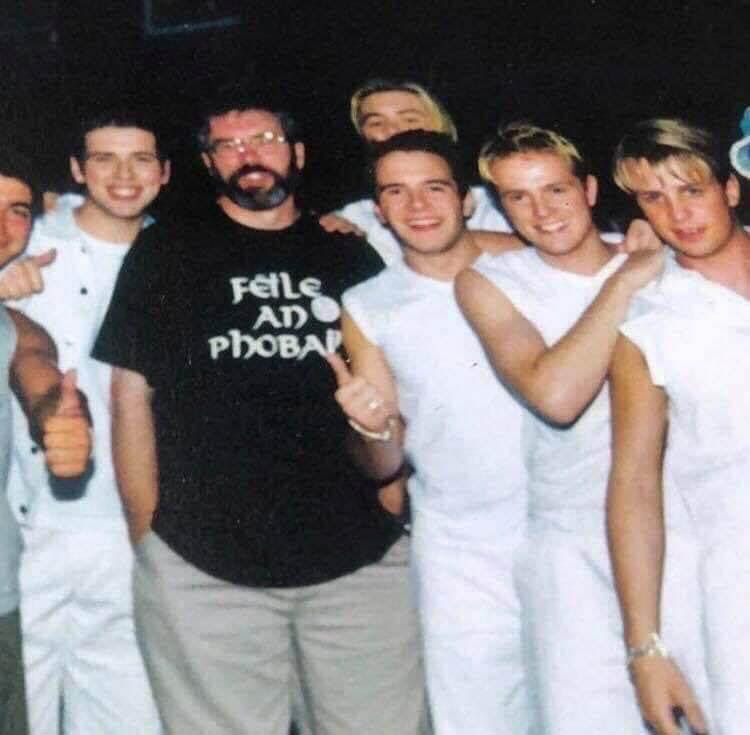

Gerry Adams with Westlife when they appeared at their first Féile

Of course, Ardoyne had its fleadh going for years throughout the Troubles.” Danny said that as a result of the attack on the two British soldiers, the British government, the DUP and the media described the people of West Belfast as “savages”.

“It wasn’t just the BBC who had described us as a terrorist community, it was actually the Secretary of State Peter Brook and the DUP called for a wall to be built around West Belfast to seal it off from the rest of civilisation, which is quite reminiscent of the call from Edwin Poots’ father when he was a councillor and called for water and electricity to be cut off in nationalist areas.

“It was quite a tough time and the idea was raised to have a festival which would showcase the creative, positive side of West Belfast which has lots of talent. It would show the side of our community which others didn’t want to show and demonstrate our commitment to peace, dialogue and democracy.

Caitlín Wilson and Sinéad Donaghy enjoying Human League

“It was decided to hold it around the ninth of August which was quite deliberate as it was the anniversary of the introduction of internment and every year subsequent to that, there were bonfires which used to be on Our Lady’s Day on 15 August and related to a religious holiday.

“The 9 August bonfires replaced that and became a political demonstration to show that internment hadn’t defeated us. “The problem with bonfires was that they became the occasion for the RUC and British Army to go wild attacking people, firing plastic and rubber bullets, to drive Saracen armoured cars through the bonfires and scatter the people.

“A lot of people lost their lives around the 9 August so we deliberately chose this date as an alternative to displace the bonfires with a positive by giving young people concerts and such to go to.” Danny told us that he had filmed the first Féile parade which consisted of a handful of GAA teams walking behind a horse and cart which made its way to Dunville Park and was followed by a bouncy castle and a band playing on the back of a coal lorry.

“What was really interesting was that in other areas we had street parties in the likes of Ballymurphy, we had pensioners being taken away for the weekend which was sponsored by some of the local clubs and there was a marquee erected at the side of the Andersonstown Social Club.

The roof of it almost toppled in because we had a heavy downpour yet people still carried on singing and dancing. “In the early days Springhill hadn’t been developed into a housing area yet and we had an open-air concert there for two or three nights which were unbelievable experience.

First proper show in 18 months - what a buzz 🙌🏻 Such an honour to headline a comedy night at a festival that has given me so many memorable experiences growing up in west Belfast. Community festivals like Féile an Phobail & others across Belfast & beyond are what we do best ❤️ pic.twitter.com/CqNM9Eek9k

— Paddy Raff (@paddyraffcomedy) August 13, 2021

“It was like Glastonbury in the heart of West Belfast only with rebel music and rock music.” Danny said that despite the positive atmosphere, the demonisation continued and in the early years they didn’t receive funding.

“In the 1990s we managed to secure £1,000 to rent an office in the Cultúrlann. In later years, we were able to get two or three full-time staff. In the mid-90s, 75 per cent of our funding came from European money.

“Belfast City Council and the Arts Council refused to fund Féile, even at that stage there was an attempt to bring it under control to make it reflect establishment values. “There were times where we had to take the City Council to court for discrimination and we also had to raise our own money for the St Patrick’s Day parade.

“In the 60s, whilst the Orange Order were allowed to march on the Falls Road, we weren’t allowed to march into the City Centre on a St Patrick’s Day parade. “That wouldn’t change until the peace process in 1994.” Danny was released from prison in 1995 and rejoined the festival management team which was on a semi-professional footing.

“We had world premieres of plays like Stones In His Pockets and A Night in November which are still playing today. Along the way we also had a pirate radio station which was run by Jimmy Teapot, Hector McNeil and Mark Holland and broadcast out of Conway Mill.

“Later on that was professionalised and we got an Ofcom licence. We trained a lot of people in broadcasting skills but was unsustainable in the long term.” According to Danny, the festival took off post-Good Friday Agreement when it took on a role of building and supporting the peace process.

“Later on I was chair of the debate and discussion group and we saw our role as building bridges with the unionist community. “We had the Orange Order come in to give lectures. It was quite difficult because a lot of people from the nationalist community had been killed by the UVF and on one occasion we had former UVF prisoners come for an entire afternoon in St Mary’s to give an explanation of what life was like for them during the conflict.”

The Féile arena is set. Come rain or shine West Belfast will celebrate! @mickconlan11 @JamieConlan11 @FeileBelfast @FailteFeirste @Kevgamblefeile @HarryBeag @BonesMacD pic.twitter.com/F1yKiq9IZb

— Bayview Media (@BayviewMedia) August 6, 2021

Danny reflected on the role of major politicans attending the festival including Albert Reynolds, former Presidents Mary McAleese and Mary Robinson, along with the like of Leo Varadkar.

“Some young people probably don’t know this but Westlife also had their first ever gig at Féile. We have also had groups like Girls Aloud performing. “It is extremely positive and has replaced the conflict and turmoil of the past.

“It has grown from strength to strength and I have no doubt that if the Falls Park was bigger, Féile and Phobail could easily put on a concert for 50,000 people.” Danny said that Féile was unlike any other festival because of its roots.

“We have had British soldiers on our panels, Gergory Campbell was one of our first panellists on West Belfast Talks Back, Jeffrey Donaldson, Arlene Foster and Ian Paisley Jr have been in.

“Féile has grown exponentially but it is not without its critics,” he continued. “Every year on the Nolan Show and in the News Letter you will have attacks on the festival because it reflects the values and political sentiments of the republican community in West Belfast.

“Four out of Five MLAs in West Belfast are from Sinn Féin, therefore by and large it is a repubican area. Yet, when the Wolfe Tones come on in the Falls Park to play republican songs, this is attacked and they want us to sensor what they play.

“If that logic was to apply, then we would have to say to Ian Paisely Jr, when you are coming on to West Belfast Talks Back, you’re not allowed to say this or that because it is offensive to people in this area. “Our opponents and critics want us to apply that criteria to the music by the likes of the Wolfe Tones.

“The Falls Park is a great venue. We have dance nights with tickets being given out in unionist areas to encourage their young people to come in, the boxing night is firmly established and we have the like of the 80s night which is always great.

“The festival attracts a lot of people and I have friends who travel from the US, England and even Poland to get a taste of a remarkable, unique community and Féile has never walked away from its roots,” he finished.