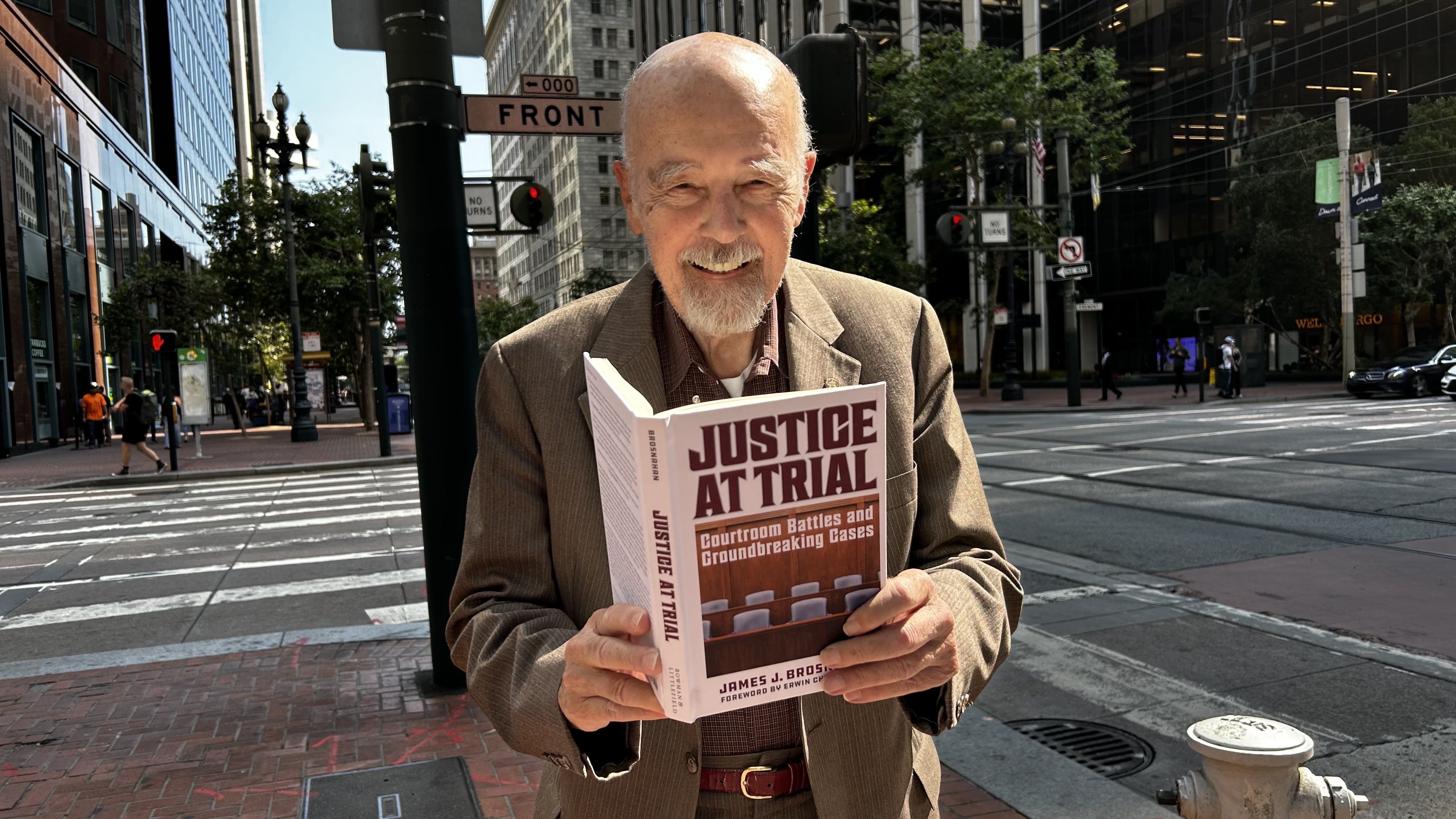

Above all else, legendary San Francisco lawyer Jim Brosnhan is a scrapper.

For sure, he represents a white-shoe law firm with skyscraper offices in the City by the Bay, but he lives for the courtroom battle.

Unlike his Brosnahan ancestors from Ireland's midlands, though, he's more likely to deploy the finer points of Tort law than fast fists to best his adversaries.

Either way, he's not one for giving up easy. Even when confined to bed as an infant for two whole years, on the advice of a quack posing as the family GP, he came back swinging and quickly reined in the head start afforded his junior school peers.

His legal journey saw him ping-ponging across the USA, from his native Boston to Houston and then to San Francisco where he has forged a stellar career as a trial lawyer. Throughout, he has remained unshaken in his fervent belief in the power of the law to right injustices — as he so compellingly spells out in his new memoir 'Justice at Trial'.

Listening to "Episode 205 Justice at Trial with Trial Lawyer & Author Jim Brosnahan" at https://t.co/eBRVx5mkuD #jury #trial #law #triallawyer #author #newbook #justice #criminaljustice #podcastshow #alittlelessfearpodcast

— Lino Martinez, Psy.D (@alittlelessfear) August 29, 2023

Along with that love of the law, the other constant in his long life — 89 years and counting — has been his Irish identity. Indeed, the number of times he references his Irish heritage in his newly-published tome will come as a surprise to those unfamiliar with the phenomenon which is Irish America.

"I grew up in Boston," he says which is, in its own way, is as much an explanation as it is a mission statement.

And yet, his branch of the Brosnahans were far from wetbacks by 1934 when Jim came along. The Brosnahans, hailing, of course, from Brusna in Co Roscommon, fled to America amidst the anguish of An Gorta Mór.

"I returned to the old family homestead in the seventies and came away incensed at the fact that my ancestors had been driven from their homeland," he told me in the offices of Morrison & Foerster 33 floors above Market Street in San Francisco.

"I had 22 aunts and uncles, 21 were of Irish extraction," Brosnahan adds. "Six of my eight grand parents came over on the death boats. Growing up, I became fascinated by Irish history and used some of the great trials of Irish patriots, basically for terrorism, in my early law classes."

Which explains in part why he wasn't deterred by British efforts to dismiss Northern Irish nationalists protesting repressive laws during the 'Troubles' as "terrorist sympathisers".

In fact, when the 1999 phone call came from a Brehon Law Society colleague asking him to help beleaguered civil rights lawyers in the North of Ireland - two of whom had been assassinated with the fulsome assistance of state forces - Brosnahan was committed even before his receiver hit the cradle.

RFJ was pleased to participate in the research for this comprehensive and important piece on the legacy legislation and the murder of human rights solicitor Pat Finucane https://t.co/ZRh7CvoqZj

— Relatives 4 Justice #NeverGivingUp (@RelsForJustice) August 31, 2023

British attempts to stonewall the investigation of the murders of trailblazing attorneys Pat Finucane and Rosemary Nelson, by his own admission, got Brosnahan's "Irish up".

Thus did he find himself an enthusiastic participant in Brehon Law Society delegations to the North of Ireland which trod where local lawyers dared not venture. He was in the room when American jurists famously hauled RUC boss Ronnie Flanagan over the coals for this failure to prevent the killings of lawyers — a fresh experience for the Chief Constable.

Brosnahan, as he recalls in 'Justice at Trial', later fumed at a prison warder who branded "people around here" as "animals" when showing the American jurists around the notorious H-Block complex. "'I did not hesitate,'" he writes, 'My people are from around here.' I waved my arm in the air. 'They left during the Hunger. They went to the United States. I went to Harvard Law School and now I'm back.' Terribly showy, but it felt good. Even if he had no inkling about Harvard Law School."

Remembering Rosemary Nelson, human rights defender, activist lawyer pro bono publico, trusted mentor, beloved wife and mother, murdered on this day in 1999.

— Patricia MacBride (@IRLPatricia) March 15, 2022

❤️ pic.twitter.com/KRzgwR4mex

Later, Brosnahan joined a picket of the UK Consulate in San Francisco (it helped that the firm's CFO, a Twomey, was there right alongside him brandishing his placard) and launched the 'Northern Ireland Alert' which ranked each member of the American Congress on their work for peace in the North.

Today he views hunger striker Bobby Sands, who died in the H-Blocks in 1981, as the ultimate "symbol of self-sacrifice for a principle".

Sinn Féin’s John Finucane is now officially Lord Mayor of Belfast.

— Mark Simpson (@BBCMarkSimpson) May 21, 2019

He’s been speaking about having a Protestant mother & a Catholic father. pic.twitter.com/0wSDtrlrIY

Undoubtedly there is a thread that leads from Bobby Sands' H-Block cell to the peace process that Irish American helped mould. Indeed, there is a delightfully vindicative moment in 'Justice' — for all those Irish Americans who stood up for due process and the rule of law in the North — when Brosnahan returns to Belfast in 2019 and meets up with John Finucane, son of slain solicitor Pat, who was then serving as Lord Mayor of Belfast.

Still practicing, Brosnahan's love of the law remains undiminished. As 'Justice on Trial' recalls, the young Brosnahan was sold on the law as a career after the first murder case he prosecuted, successfully, in Phoenix, AZ, back in 1961. "In that first trial, I learned an important lesson," he writes. "I loved the action, the contest, and the instantaneous need for decisions on my part. I wanted to try a lot more cases."

His belief in the law as a tool of social justice was shaken only once — when Presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy was shot dead in 1968. "I was head of the California Lawyers for Robert Kennedy and was heading home after celebrating his primary win when news came on the radio that he had been shot in Los Angeles. That weekend, I thought a lot about my chosen path but I remembered an Irish saying — 'You shoot one Irishman, and a hundred will come' — and decided that I wasn't giving up. It was a bit intense but that's how I decided to stay in the law and make the biggest impact I could. And, in very modest ways, that is what I am continuing to do today at 89."

There is no such Irish saying, as far as this writer can tell, but there surely should be.

The delightful 'Justice at Trial' chronicles the highlights of seven decades in the legal trenches (his firm's website more modestly describes his legal adventure as lasting over fifty years), ranging from defending the First Amendment right of the San Francisco Chronicle to publish to exposing an FBI stitch-up of a Filipino dissident opposing the Marcos dictatorship.

Brosnahan is at his very best when pitting himself against unjust laws which target the marginalised. He delivers a standout chapter on his bid to defend Catholic social activists in the Mexican border town of Nogales who were providing sanctuary to immigrants crossing the US border.

Despite Brosnahan's best efforts, the Bible and the American judge in the case didn't see eye-to-eye and his clients were convicted. Among them was 60-year old widow Socorro Aguilar who ended up behind bars (briefly) for following Christ's instruction to love your neighbour. Ironically, she had earlier brought the American attorney to a Mexican jail during his visit to Nogales to meet prisoners from across Latin America who had been jailed by the authorities for entering the country illegally. "I had a growing awareness that people only leave their home if they must," he writes in 'Justice'. "The road is dangerous and lonely. These pilgrims decided to head into the unknown...Historically, that flow of oppressed people has been the story of the United States, the Irish fleeing hunger and British colonialism, the Jews fleeing pogroms and the Puritans fleeing religious persecution. These men and women, as others before them, made the difficult choice to leave their homes. Many times throughout my law practice I have wished our government officials could witness what really happened in a case of mine. Standing with Socorro in that Mexican jail was one of those times."

Meanwhile, the wheeling and dealing between prosecution and defence outside the courtroom — on which the lives of many hang — also comes under the spotlight in an account of his advocacy for an innocent man who spent 17 years in jail for a fatal arson in which he played no part. Across 150 trials before a jury, and two luckless cases argued before the Supreme Court, Brosnahan scored many victories but he also witnessed the shortcomings of the courts. "When I became a lawyer," he writes, "I was startled by the difference between law and justice. An imaginary character came closer to the truth. Sherlock Holmes...tells Watson casually, 'Justice is what we attempt. Law is what we have to live with.'"

Slowing down but not stopping, Brosnahan has adequate time to indulge his passion as a writer by penning occasional pieces for the Irish Echo. And even if not entering the ring, his eye remains on the arena. He may not be in the maw of the scrap but he can still urge on the justice fighters. And when skies darken, his faith in the law, in lawyers and, indeed, in judges, is absolute. "My belief in trial lawyers serves me as an antidote to the suggestion that our country may have a dictator in the future," he concludes in 'Justice at Trial'. "I believe lawyers will stand against such a threat to our democracy. There are a lot of us."

Thankfully, Jim Brosnahan is not the only one up for the scrap.