After the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1658, the persecution of Catholics and their clergy in Ireland continued unabated. On July 1, 1681, to the amusement of throngs of baying savages, the decapitated and disembowelled corpse of the Catholic Primate of Ireland, Oliver Plunkett, was dragged through the streets of London strapped to a jail door which was dyed scarlet by his congealing blood.

In the Act of Settlement at the end of the Williamite war in 1691, the persecution of Catholics in Ireland became the official policy of the English establishment. Under the Penal Laws they were denied the right to vote, practice law, access higher education, own property or assemble freely. And to qualify for any meagre redress of this tyranny, they were forced to give the Oath of Abjuration, which was a public declaration that their religion was founded on heresy and idolatry. They also shared with Presbyterians the indignity of having to pay a tithe to the Church of England.

But as the persecution of Catholics continued, the policy of persecuting their clergy was being reassessed. Eventually it was realised that if the subjugation of Ireland was ultimately to succeed, the persecution of the Catholic hierarchy would be counterproductive. It was realised also that superstition and ignorance, if encouraged, manipulated and properly managed, would be a powerful asset to this project.

Extravagant

And if Oliver Plunkett had been the leader of Ireland’s Catholics one hundred years later, in 1795, when the British government built Maynooth College to train Catholic clergy, he would not have been hanged, drawn and quartered. Instead, he would more likely have been a feted, revered and courted guest in the extravagant and lavish mansions of the English aristocracy.

From then onwards, the Catholic hierarchy would never again be skulking fugitives, saying Mass in secret before being hunted down and killed like animals. Instead, they would now become the moral authority for English tyranny in Ireland, a pliant and reliable tool in the service of the British government. They would provide the moral sanction for the criminal activities of every thief, murderer and despot that England would send over to Ireland and would become a major and permanent impediment to any campaign for justice, peace, human rights and Irish liberation.

It is no surprise, then, that the massacre of thousands of unarmed United Irishmen in Enniscorthy in 1798 occurred after the Catholic hierarchy had successfully pleaded with the rebels to lay down their weapons. And when Margaret Thatcher travelled to the USA and protested at the endorsement of Fair Employment Legislation for American firms in Ireland, she could rely on support from the then head of the Catholic Church in Ireland, Cardinal Cahal Daly, who also intervened on behalf of the Orange Order – a right wing reactionary group which British agents set up, also in 1795, from the ranks of an 18th century sectarian murder gang – to stop the non-violent and legitimate boycott of their businesses during the Drumcree crisis.

Nor was it surprising that the English Cardinal, Basil Hume, travelled to Ireland in 1981 and pleaded with Catholics not to vote for Bobby Sands in the Westminster election.

Tyranny

But the slavish loyalty of the Catholic hierarchy to the English establishment, and their fawning complicity and subservience to its tyranny in Ireland, was portrayed at its very worst on a rainy August evening in Mayo in 1879.

It was earlier in the 19th century that armies of Irish navvies converged on British cities to find work during the Industrial Revolution. Roads, railroads, bridges and factories were being built and canal systems were being dug and developed, connecting cities to ports, coal mines and market places. The increasing demand for food to feed this workforce provided a great opportunity for the landowners in Ireland who exported grain and livestock and made lucrative profits.

The people who produced this food could only watch as it was shipped out of Ireland from every port under the protection of military guards. Forced to survive on the poorest quality lumper potato, nearly two million people succumbed to starvation when this vegetable was destroyed by blight.

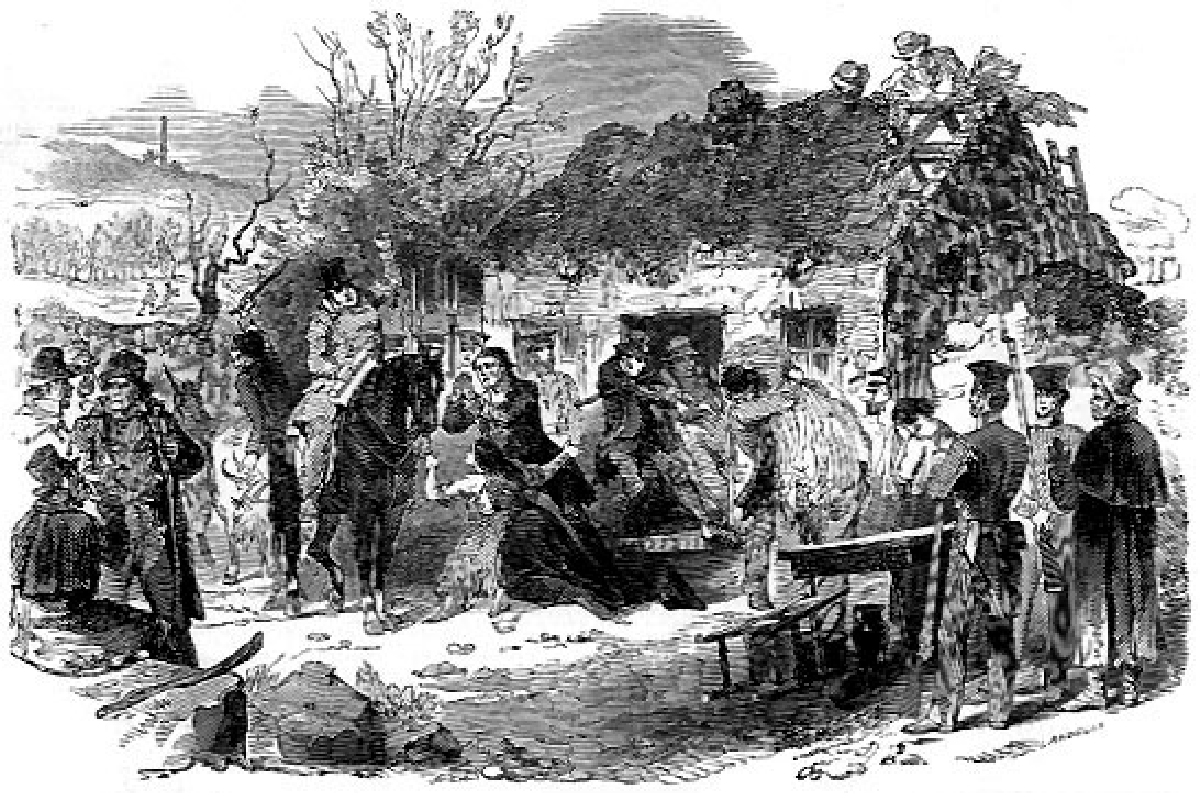

But the ending of the Famine did not end the insatiable avarice of the landlords. With increasing rents came land clearance schemes to make way for the more profitable sheep farming; the threat of a second genocide also loomed. Widespread evictions were carried out of impoverished Irish tenants who could not pay the exorbitant rent increases.

Those who had survived the starvation were now faced with the threat of freezing to death in the icy bogs, lanes and ditches of rural Ireland. And before their last breath would vaporise in the freezing air, they would still be robbed of their last pittance by a Christian church, the Church of England, and its Christian leader, Queen Victoria, who had previously written a letter of protest to the Turkish government because they had sent food to Ireland for Famine relief.

In response to this impending catastrophe, Michael Davitt, whose family had been evicted in 1847, returned to Ireland and organised a campaign of popular resistance. His calls for unity and resistance were answered by massive crowds who came to hear his orations at Castlebar, Claremorris and Straide, where Davitt was born. The focus of this campaign was the Mayo Land League, which he set up following a meeting in Irishtown in April 1879 which was attended by over 15,000 people. The campaign quickly escalated and a Land League was set up in Scotland where tenant farmers were also facing eviction by their landlords. In response, Orange Lodges were sent to Skye to evict the striking crofters and to Achill Island in Mayo to support tyrant landlord, Captain Boycott. But as support for the Land League grew it attracted growing opposition from the Catholic hierarchy and drew withering condemnation from their pulpits. Not that the landlords were all English gentry. One of them was a Catholic priest, Canon Ulick Burke, from Knock village in Mayo, who had increased his rents and threatened his 22 tenant families with eviction. In response, Burke became the target of a rent strike organised by the leaders of the Land league. The leadership of the Land League were immediately condemned by the Archbishop of Tuam, John McHale, a colleague of Burke, who publicly warned the tenant farmers that the leaders of the Land League were strangers who were using them to service their careerist interests. In response, Davitt reminded him that he had been born and evicted in Straide, and that most of his career had been spent in prison, and in all probability that was where most of his future career would be spent.

The leadership was also condemned by another colleague of Burke and supporter of the landlords, Archdeacon Bartholomew Cavanagh, Parish Priest of Knock and a vociferous enemy and critic of Davitt and the Fenian revolutionaries. But when Cavanagh condemned the Mayo Land League from the pulpit in Knock in August 1879, his language was so inflammatory that it infuriated many people and led to a massive protest outside his church. According to the Connaught Telegraph, the crowd was estimated to be between 20,000 and 30,000 people – an event which would be unprecedented even in 21st century Belfast, let alone 19th century rural Ireland. Burke was so alarmed by the size and mood of this crowd that he immediately reduced his rents by 25 per cent. But Cavanagh was unwavering in his opposition to the campaign of agitation.

On the evening of August 21, just three days after the protest, news spread throughout the village of the presence of three heavenly figures that stood at the gable wall at the south end of the church. Many accounts of the incident have since been written by Catholic clergy, including one by Monsignor Michael Walsh in 1958, published in a further eight editions since then.

According to Walsh, the first witnesses were Mary Beirne, whose job it was to lock up the church, and Mary McLoughlin, who was Cavanagh’s housekeeper. They both saw lights above the church and what they first thought were statues at the gable wall. Other people from outside the village saw the sky lit above the church. The news quickly spread beyond the village and soon a crowd had gathered outside the church to witness the event. It also drew the curiosity of a dying woman who got out of bed and tried to walk to the scene before she collapsed at her front door.

Mary McLoughlin left the scene and returned to the house, which was one hundred and fifty yards south of the church, where she informed Cavanagh, who was at home at the time. He told her that she was probably confused by a reflection in the window, but he didn’t go out to investigate what had attracted the crowd outside his church.

The figures they saw were said to move off the ground when approached by other curious spectators. And when someone tried to touch the feet of one of the figures, she found that she was touching the gable wall.

In a follow-up enquiry set up by the church and headed by Cavanagh, over 15 witnesses were interviewed, all of whom claimed to have seen an apparition of three heavenly figures accompanied by an altar and some angels. The event happened at the gable wall at the south end of the church, and lasted two hours, from early dusk until darkness.

There is no known record of any proper and independent inquiry into what happened that evening, and we may never know the identity of those who orchestrated and carried out this mischief. But the eyewitness accounts are unquestionably the most accurate indicators that we still have.

The church itself sits on flat ground which remains flat for about another thirty yards where now exist rows of water taps. From here the underlying geology begins to dip southwards quite steeply for about another hundred yards, to where Cavanagh’s house would have then stood, before rising sharply again. And somewhere between the church and this house a lane ran eastwards from the road.

Detection

We can only speculate on where the perpetrators of this stunt were located. They would have had to be close enough to the gable wall of the church to accommodate the range of their light source and far enough away to avoid detection, and somewhere between the church and Cavanagh’s house they were cunningly concealed. The ‘apparition’ could not have happened anywhere else since only the flat gable at the south end of the church could function as a screen.

Nevertheless, to focus a transparent image from beyond the slope of the hill, and to shift it when curious spectators came too close required trial and error, considerable dexterity and almost certainly more than one operator. It is not surprising, then, that people saw light beams in the sky from beyond the village, and images moving about the gable wall.

At the time of the incident, apparition hoaxes were already popular throughout Europe after the Church had discovered their potential. And they all had two things in common. Firstly, they always happened when the Church was facing major difficulties. And secondly, no apparition has ever been witnessed by any member of the Catholic clergy.

The second statistic is unremarkable in the most famous apparition of all in Lourdes, since this hoax was not based upon eyewitness accounts, but upon the testament of a teenage girl whose imagination was driven into chaos by manic depression. But at Knock this event occurred in the grounds of a Catholic church, illuminated by lights which were seen from outside the village, at the gable wall of the church which was in full view from the residence of the parish priest, which lasted for two hours and drew crowds from far and wide.

If the clergy were not party to this deceit, then it is remarkably strange indeed that not even one of them came out to see what was attracting large crowds to an event within the grounds of their church. Given the timing of this incident, the immense difficulties facing the Church, the unpopularity of its hierarchy and the eyewitness accounts, it is clear that this skulduggery was at least orchestrated and approved by Cavanagh and his clergy, if not directly carried out by them.

So pathetic in its design and so amateurish and crude in its execution, this infamous event still dupes people from throughout the world, and perhaps this is the real miracle in this depressing story.

Today, schoolchildren would be very familiar with the use of light reflections to project transparent images on to screens in their classrooms. And in 1879, the science of optics was well advanced, given that photography had been used extensively by soldiers in the American Civil War more than a decade earlier.

Nevertheless, occurring as it did in rural Ireland at that time, this trickery must be seen as a masterpiece of deception and manipulation. In an intriguing contest to win the hearts and minds of the population, its perpetrators managed to rescue the Church from terminal decline, but failed to defeat the Land League, its objectives or its leaders, whose endeavour eventually overcame the greed of the grasping landlords and saved Ireland from another impending genocide.

Davitt died in Dublin in 1906 aged sixty. His grave is in Straide village near where he was born and adjacent to the ruins of a tenth century abbey that was destroyed by Oliver Cromwell. Nearby, a small building houses a museum dedicated to his memory. A plaque above the door bears the following inscription which he penned before his death.

“To all my friends I leave kind thoughts, to my enemies the fullest possible forgiveness. And to Ireland the undying prayer for the absolute freedom and independence, which it was my life’s ambition to try and obtain for her.”

n The story of the Famine, the Land League and the Fenian revolutionaries in Connaght will be told on a weekend tour presented by Irish Historical Tours. The venue will be the Great Western Hotel in Sligo and the tour will be hosted by the eminent historian, Bernard O’Hara. The event will take place from Friday May 25 to Sunday May 27 with a coach laid on. Details of cost, bookings and arrangements can be had from Irish historical Tours. Telephone Jack on 02890 596217, or by mobile on 07598946162.