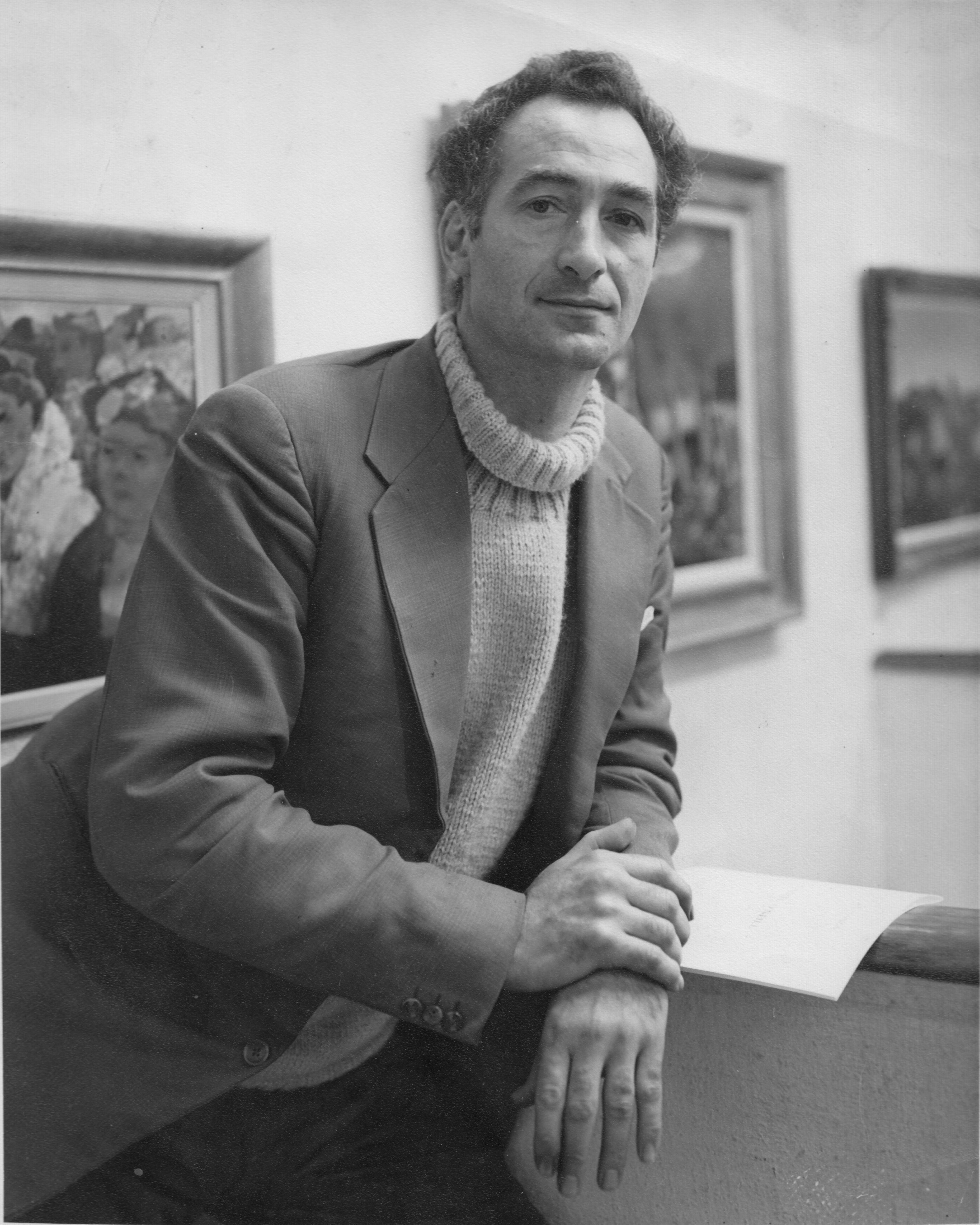

Daniel O'Neill: Romanticism & Friendships is a newly-published book by Karen Reihill on West Belfast artist Daniel O'Neill who, with fellow-Belfast boy Gerard Dillon, is among the shining lights of 20th Century Ulster artists. The book is available from the publisher direct or from An Chultúrlann bookshop. This excerpt is from the opening chapter of the new publication.

Daniel O'Neill was born into a working-class Catholic family in Belfast. During the 1880s, working-class Catholics from rural Ulster flocked to industrial Belfast for jobs.

During the 1920–1922 War of Independence, sectarian violence and intimidation led to increased segregation of working-class Catholic and Protestant communities in Belfast, which caused the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland to struggle to gain employment in the new Civil Service, to stand in parliamentary elections, or to serve in the security forces. Over time a continuous tribal war between the two communities resulted in a heavily polarised city, with communities that identified as East (loyalist) or West (nationalist).

After the War of Independence, the Northern Ireland Parliament was set up by the majority Unionist-led government under James Craig, which continued to have strong ties to Britain.

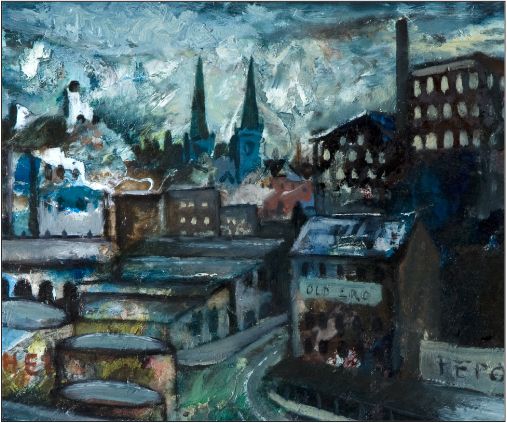

Cityscape (1947) Signed, Oil on board, 35.5 x 45.7cm © The Collection of Queens University Belfast.

Growing up in Belfast during the 1920s pogrom and the 1930s Great Depression would have been challenging for O’Neill’s family. In the 1940s, the linen industry declined and unemployment rose due to a drop in the level of emigration. As tensions in Europe increased, the aircraft factory, Short and Harland increased its productive capacity, but only Protestant factory workers benefited from this.

ICONIC IMAGES: Dan O'Neill

O’Neill’s family belonged to the minority population living in a Catholic enclave in West Belfast. They lived in a Victorian redbrick terrace at 4 Dimsdale Street, overshadowed by Mackie’s iron factory. O’Neill’s Grandmother, Ellen O’Neill was a widow in 1911 and with three children, Bernard,(24) Francis(19) and Minnie,(14) to look after she took boarders in to make ends meet.

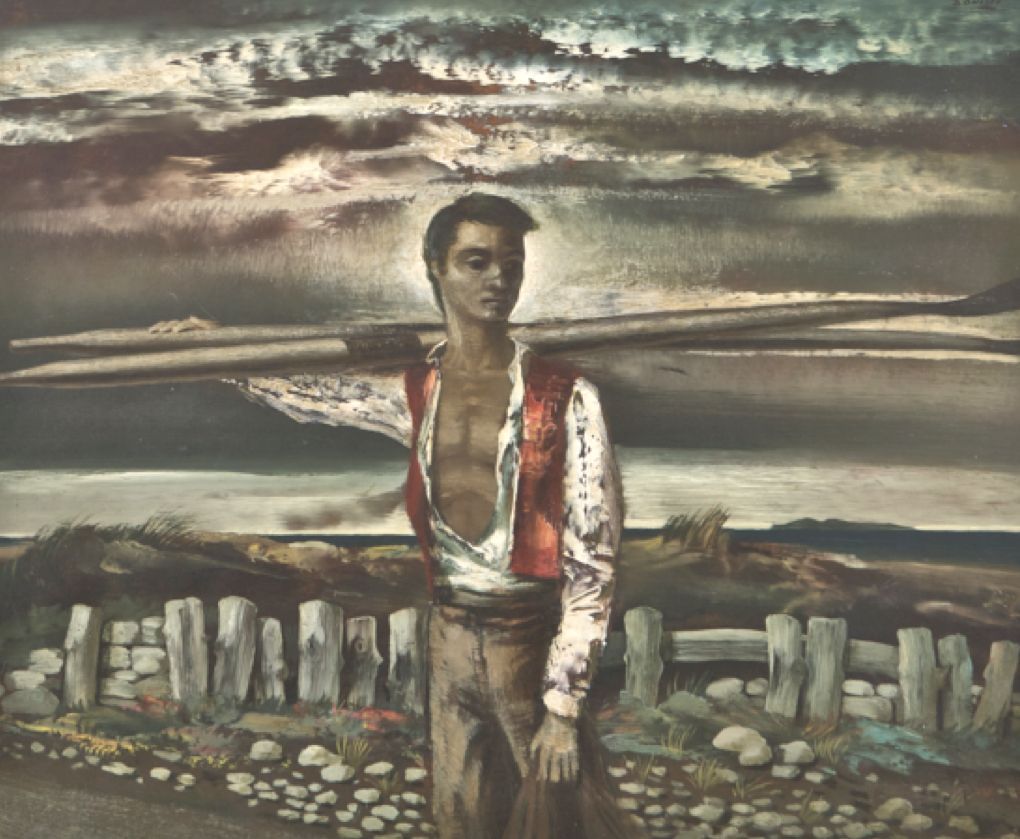

One of the boarders was Belfast-born, Mary Cash. She married Francis O’Neill on 27 July, 1917 and their son, Daniel was born on 21 January 1920, during the War of Independence. He had two sisters, Mary Brigid (b. 1921–?) and Brigid (1922–1993), known as Bridie, who remained close to her brother throughout his life. Mary Brigid is thought to have died in childhood. O’Neill returned to the subject of sisters regularly in his painting, which would suggest the death of his older sister had left its mark. Following his education at St John’s school on Colinward street (off Springfield Road), O’Neill left school to become an apprentice electrician. In later years he told friends he often felt self-conscious because of his limited education and that he felt socially inadequate at exhibition openings, where he would be surrounded by Dublin’s social elite in Victor Waddington’s gallery.

Little is known about O’Neill’s father, Francis [Frank] O’Neill. An electrician by trade, he worked in a telephone company in Philadelphia and most likely encouraged his son to follow his trade during the 1930s economic depression years. We do not know anything about their relationship, but an early work of a death scene Death, in response to the loss of his father from cancer, does suggest that his father’s suffering from the wasting disease in the early 1940s was a significant family event. Interestingly, around the same time, Gerard Dillon executed another vigil scene, The Widow Woman. While both paintings are stylistically similar, they reveal how different their approach was to life events. The flattened linear perspective in both paintings shows the influence of the Italian primitives.

But unlike Dillon’s painting, there are no Catholic symbols included in O’Neill’s Death. The focus of Death centres on the expressions of grief from family members supporting one another around the death bed. Dillon, however, chooses humour to deflect from the subdued scene in The Widow Women. The widow’s exaggerated size and expression evokes humour, as does the location of the widow’s husband, who is depicted at the top of the canvas. Both artists were adored by their mothers, who were devout Catholics, but as the eldest and only male child in the family, O’Neill would have had to carry a heavy burden of responsibility after his father died.

Mary O’Neill (nee Cash) adored her only son and ‘lovingly’ called him ‘Danny Boy.’ She indulged him with gifts throughout his adult life and only wished to see him in fine-cut clothes. Meeting the painter in the 1940s, one writer remarked on his dapper appearance, ‘He [Daniel O’Neill] wears well-cut Irish tweeds of subdued colour, and speaks in a voice so softly modulated that it is almost impossible to believe that he is a native of Belfast.’ Mary was the first to notice her son’s early talent for drawing, and O'Neill remarked later that his drawing talent was ‘possibly inherited from his mother, who had won a drawing prize at school.’ It is possible that, acknowledging her son’s talent, she decided to support him in whatever way she could, despite the lack of opportunities in the visual arts in Belfast at that time. From the age of twelve, O’Neill was painting with watercolours and studying the Italian Renaissance painters from art books. Mary continually encouraged her son to draw by supplying him with paper and watercolour paints; she soon became aware that her son’s perception of the world was different from that of other boys and that her son had a vivid romantic imagination.

While other children light-heartedly drew cowboys and Indians, he [O’Neill] was intensely serious and painted lofty castles defended by knights in shining armour and always instead of drawing inanimate objects, he always wanted to draw from life.

When war broke out in 1939, O’Neill was working as an electrician in Belfast. It was announced that the South was not going to engage in the war effort. Recovering from years of conflict, the Free State under Éamonn de Valera’s Fianna Fáil government wished Ireland to remain neutral and so throughout the war people lived in what became known as the Emergency, when the government introduced sweeping powers affecting censorship and the economy. However, despite rationing and censorship, Dublin was an idyllic place to live for refugees fleeing Nazi Europe or artists wishing to live in a country unaffected by war. One account indicates that Dubliners adjusted to restrictions with little difficulty:

Dubliners still danced at the Shelbourne, Metropole, Gresham and Clerys, arriving on two wheels instead of four. Formal dress was de rigueur. Gentleman in white ties tucked their tails up beneath them on the saddle and wore bicycle clips and their partners perched on the crossbar holding the long skirts of their evening dresses up out of the mud... the city seems safe and cheerful, far from the uncertainties of the Blitz.

In Belfast, the Unionist-led government viewed Catholics in the Free State as anti-British after they refused to allow British and allied forces access to their ports.

During the war some Catholics living in Belfast viewed the Free State as richer than the North. The Belfast writer, Gerard Keenan (1927–2015) later remarked, ‘The war years in Dublin must have been terrific fun; virtually no rationing; virtually no black-out; no fear of air-raids; lots and lots of wartime money floating around’. War did, however, change people’s lives in Belfast. Groups of writers, poets and artists came together in unusual circumstances. Conflict and religious division in Ulster cooled as German bombers appeared in their skies, threatening their very existence. The bombing of London in 1940, so soon after the Spanish Civil War, might have been an impetus to trigger O’Neill’s creative consciousness. His distinctive romantic style indicates he was deeply concerned about life and those around him and this emotion would remain a constant element in his work until his death.

Against this backdrop of impending war and political unrest, O’Neill was drawn to the Belfast Reference Library to learn more about art. Anne Marie Keaveney remarked that the head librarian, Mr Jenkinson, ‘would, contrary to library rules, allow O’Neill and his fellow painters to borrow illustrated texts for the weekends, thereby enabling them to study colour reproductions of the European Moderns’. At that time contemporary Ulster painting consisted of traditional pen and ink drawings, watercolours and oil paintings that seemed to suit the public’s conservative tastes. Mural paintings of a bewigged King William III on his white horse at the Battle of the Boyne adorned gable ends at street corners, and traditional portraits and landscapes of Ulster would have hung at the annual academy shows. O’Neill would most likely have been aware of Ulster’s established painters, William Conor (1881–1968), Frank McKelvey (1895–1974), Paul Henry (1876–1958) and James Humbert Craig (1877–1944), but their conventional style would not have resonated with his more romantic imagination.

In Dublin in 1940, the arrival of refugee artists from London and returning Irish painters working abroad resulted in the development of a bohemian and distinctly avant-garde art scene during the Emergency. A gay couple from London, Basil Rákóczi (1908-1979) and Kenneth Hall (1913-1946) held their first exhibition of The White Stag group in April 1940. Their subject matter from the West of Ireland initially appeared fresh and was largely representational with a fresh child-like quality which appealed to the critics in a time of uncertainty, fear and a Europe dominated by fascism. Referring to the time, James White commented, ‘The coming of the Second World War had a surprising spin-off for the artistic life of Dublin. The restrictions to travel, both in and out of Ireland, forced organisers in various disciplines to rely on native artists.’ In this atmosphere, critics seemed to be negative in their attitudes towards traditional painters and academic art shown at the annual Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA). In the city’s political neutrality and resulting isolation, a surge of interest in local artists would lead to an important development of O’Neill’s career.

You can buy this book in local bookshops, including An Ceathrú Póilí in An Chultúrlann, or on-line from Frederick Gallery Bookshop.