Schoolchildren protesting at the multi-million pound transit hub in West Belfast this week to demand recognition for the Irish language could well brand government bodies denying them parity of esteem as slow-learners.

For since the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, long before the young demonstrators were born, government here has been under an obligation to take "resolute action" to promote the Irish language.

And while there has been much foot-dragging by certain departments and agencies, others have implemented — without controversy — the type of measures being demanded by campaign group An Dream Dearg, most notably at the NISRA offices on the Stranmillis Road which opened seven years ago.

WRITING ON THE WALL: Normalisation of Irish at the NISRA hq

According to the peace accord, "the British Government will in particular in relation to the Irish language, where appropriate and where people so desire it:

• take resolute action to promote the language;

• facilitate and encourage the use of the language in speech and writing in public and private life where there is appropriate demand."

That pledge was given in the context of the UK considering signing the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages - which it eventually ratified in 2005.

However, despite commitments under the Good Friday Agreement and the Charter, many government departments, councils and arms-length bodies across the North have provided only minimal recognition of the Irish language - in the case of the new Transport Hub, virtually zero recognition.

According to a report commissioned by the Department of Finance here in 2016, "only a few departments had opted to take 'resolute action' for the promotion and development of the Irish language (including) routine translation of documentation, bilingual advertising, press releases in Irish, employment of Irish language officers."

The same report says that if departments were to adopt plans to deliver on the "resolute action" commitment, they could "create Irish signage and corporate identity (and) make Irish more visible in public areas" - the very omissions which have sparked this week's stand-off over the English-only transport hub.

CARR-CHLÓS: Bilingual signage at NISRA offices in Belfast

Armed with that report, the Department of Finance went on to commission bilingual signage throughout the new Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency building on the Stranmillis Road.

Established in 2000 and with wider application than the EU states, the Charter was designed to "protect and promote regional or minority languages as a threatened aspect of Europe's cultural heritage".

Under the Charter, "departments and associated bodies should take account of the wishes of the language speakers as they plan their activity"

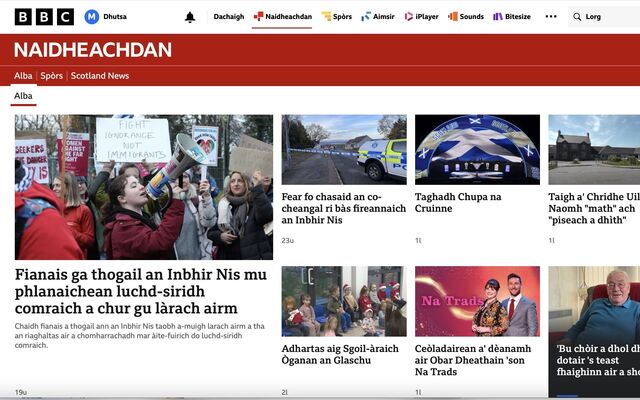

Conversely in Scotland, where Gaelic is also protected under the Charter and the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005, actions have been taken to 'normalise' the use of Gaelic through a proactive strategy involving the Government, the public sector, the private sector, community bodies and the individual speakers of the language.

Ciarán Mac Giolla Bhéin of rights group A Dream Dearg said the latest row over the transport hub showed that past promises of action on Irish were "worthless".

"The Translink decision on the Transport Hub shows that we still have a long road to travel before the Irish language has parity, equality and justice — despite significant developments for the language in recent years," he said, in Irish. "Nevertheless, our community is organised and we are not going to accept despicable decisions like this anymore."