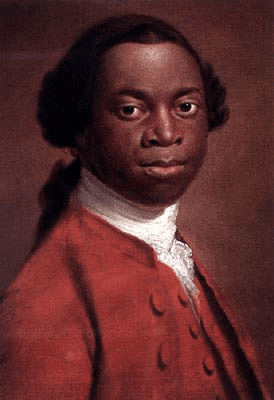

BORN in what is now Nigeria, Olaudah Equiano was sold into slavery in 1756 at the age of 11.

After spells in Barbados and Virginia he spent a decade travelling the world as a slave to a British Royal Navy officer. In turn he was sold to a merchant in Montserrat, a British island in the Carribean. By now he was self-educated and was permitted to buy his freedom for £40 which was then the equivalent of a professional annual salary. He then travelled as an explorer and eventually settled in England in 1760. With encouragement from slavery abolitionists he began writing his memoirs and had them published in 1789.

This was one of the first books published by a black African writer and it was an immediate success. By 1790 a fourth edition was published and Equiano came over to Ireland to promote the book. He spent several months in the south, visiting Dublin and Cork before coming north to Belfast where he spent three months. He visited all the local bookshops and travelled to fairs and markets throughout the north.

He was probably the only black man that most people had ever seen and he was well able to hold the attention of a crowd as he told stories about the treatment of slaves. It's estimated he sold over 1,900 copies in his nine months in Ireland. He wrote that he found “the people extremely hospitable, especially in Belfast’. During his few months in Belfast he was the guest of Samuel Neilson who then lived where the Northern Whig building is situated.

McCabe’s speech is not recorded but the last sentence he is supposed to have uttered has been part of Belfast’s folklore , “May God wither the hand and consign the name to eternal infamy of the men who will sign that document.

Neilson was a close friend of Thomas McCabe who had attended the meeting at which Waddell Cunningham proposed to his fellow townsmen and business owners to become involved and sign up to the formation of the Belfast Slave-Ship Company. In 1786, several Belfast merchants, including Waddell Cunningham, had called a meeting at the Exchange and Assembly Rooms in Waring Street. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss setting up a slave-ship company.

Can't believe I picked this up for £3?!?? Excited to read it and start work on revamping my #AST Atlantic Slave Trade course 📚💻 #history #OlaudahEquiano pic.twitter.com/8A8loNoJMU

— Miss McMillan (@MissMcMillan17) June 14, 2021

Their plan was to ship goods to the Gold Coast, purchase the captured African slaves, deliver them to the West Indian sugar plantations, returning to Belfast with cargoes of sugar and brandy.

YOKED AND CHAINED

When ships anchored off the African coast, boats were launched and sent up the rivers seizing men, women and children. They were escorted to the coast, yoked and chained together like oxen and kept on the move by the heavy rawhide whips of their escort. Slave decks on the ships had a head room of barely half a metre so that these poor people had to lie down for the whole voyage, unable to sit up. What their condition was after a six week journey is better left to the imagination.

It has been said that Cunningham did not know the full implications of the trade.

No-one in Belfast or in Britain or Ireland knew more about the slave trade. He had bought and sold slaves while he lived in New York – Cunningham had served a jail sentence for his involvement – before returning to Belfast with his fortune. He and his brother-in-law owned at least four ships. They saw an opportunity to acquire vast wealth from this trade, similar to that achieved by merchants in Bristol and Liverpool.

The meeting discussed ways and means without a dissenting voice and in a few minutes the required capital was oversubscribed. All that was now to be decided was the choice of a sea captain and crew. What they hadn't taken into account was the attitude of many radical Presbyterians in Belfast. Thomas McCabe, a goldsmith and watchmaker from North Street and a member of the First Presbyterian Church in Rosemary Street, had arrived as the meeting was nearly over. The business was explained to him. He is said to have stood silently for a few minutes before he began to talk. He discussed the aims and objects of the company, ticking off the points one by one. Cunningham’s attempts to answer him were silenced. One by one the businessmen present withdrew their support which meant that the slave-ship company never saw the light of day.

#CamRefWalk site 3, St Andrew's Chesterton and its plaque to Anna Maria, 4yo child of antislavery campaigner Olaudah Equiano. Does one of these worn gravestones mark her resting place? #RefugeeWeek2021 pic.twitter.com/aVCR9uUwHp

— Aidan Baker (@AidanBaker) June 14, 2021

McCabe’s speech is not recorded but the last sentence he is supposed to have uttered has been part of Belfast’s folklore , “May God wither the hand and consign the name to eternal infamy of the men who will sign that document.

Thanks to the intervention of Thomas McCabe, Belfast did not become a major slave trading port and Olaudah Equano had a hero’s welcome just a couple of years after the ill-fated meeting

.

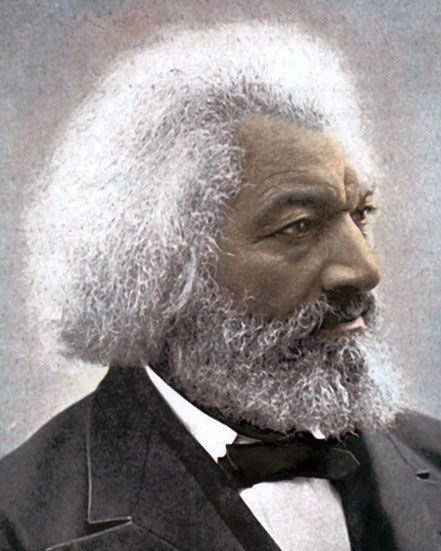

Almost 50 years later Belfast played host to another freed slave. Frederick Douglass was as born into slavery in Maryland in 1818 and, once he had escaped, became one of that century's most prominent abolitionists.

After he escaped, in 1838, he got married, changed his surname, and joined the anti-slavery movement becoming one of the most well known campaigners of his time, with a talent for public speaking, as he travelled around telling people about life as a slave.

GREATER RISK OF RECAPTURE

However, there were some elements who doubted his story. Frederick went on to publish his autobiography entitled ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave’ in 1845 as a means to tell his full story. This put him at an even greater risk of recapture and so he sailed to Ireland and Britain.

He spent three months touring Ireland in 1845, speaking in Dublin, Waterford, Limerick and Belfast. Douglass returned to Belfast in June 1846 and gave further talks in support of the abolition of the slave trade.

Fredrick Douglass’s visits to Belfast left a lasting impression on those who heard him speak.

The Belfast Newsletter of the 29 September 1846 reported that a group of women in Belfast were inspired by his visit to set up an ‘Anti-Slavery Association’ in late 1845. The Association invited people to contribute items to be sent and sold in America at Anti-Slavery bazaars. These bazaars were one way the abolitionist movement could raise much-needed funds.

Congratulations to the winners of the Frederick Douglass Global Fellowship. When you are in Ireland, walking in the footsteps of Frederick Douglass who traveled there 175 years ago, remember that you too have the capacity to be great. pic.twitter.com/CAjlBqZ5yz

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) March 17, 2021

Probably the best known member of this movement was Mary Ann McCracken.

A proposal to erect a statue to Frederick Douglass was passed at Belfast City Council last November. The statue will be in Rosemary Street where he made a famous speech in 1845.

"This statue will not only be a tribute to Douglass, but also to the anti-racism movement in Belfast and across Ireland," said Ciarán Beattie of Sinn Féin.

"From Belfast to the world, this is a clear and unambiguous message – Black Lives Matter," he added.