Living With Ghosts, The Inside Story From A ‘Troubles’ Mind is published by Merrion Press, £16.99. (Áras Uí Chonghaile will host a conversation with Barney Rowan at 7pm sharp on Monday 19 September to mark the publication of this new title.)

IT was the day after the IRA bombed the Grand Hotel in Brighton when I got the call summonsing me to a street off the Falls Road to take delivery of the statement.

The confirmation of the failed attempt to kill the British Prime Minister came in a small piece of folded notepaper; lavender coloured, if I recall, and with the following paragraph, neatly typed: “Mrs Thatcher will now realise that Britain cannot occupy our country and torture our prisoners and shoot people in their own streets and get away with it. Today we were unlucky, but remember we only have to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always. Give Ireland peace and there will be no more war.”

The note was handed over on behalf of P O’Neill, the anonymous individual who signed off IRA statements, by a man who I met from time to time. It has been a while since we’ve caught up, but when we do, sometimes over coffee, the details and circumstances of that encounter all those years ago are never mentioned. It’s as if it never happened.

I tell this story by way of explanation. My employer, the Press Association, the national news agency for the UK and Ireland, was a convenient post box for the republican leadership back then. It supplied, and continues to supply, all the local daily and national newspapers, and broadcasting organisations with a round-the-clock news service. It guarantees that the output can reach an international audience within seconds of transmission.

It wasn’t hard to imagine the impact those words had on the delegates who survived the carnage inflicted at the October 1984 Tory Party conference.

@BrianPJRowan @molloy1916 @newbelfast reading Barney Rowan's fantastic new book Unfinished Peace. pic.twitter.com/50JBh8gv8A

— Joby Fox (@jobyfox) April 12, 2016

Unlike Brian Rowan I never actually met P O’Neill. He got to know five of them during his time as the BBC’s Northern Ireland security correspondent, maybe pre-arranged at a café in West Belfast or somewhere down the country. I was never invited to the table. The statements I received were usually read out over the office or home telephone. I just had to have a pen and paper handy, a good shorthand note (120 wpm), and even though the caller with the familiar accent was always somewhere this side of the border, he always ended the conversation with the reminder: “Make sure you say this was issued in Dublin.”

So I have a fair idea how Rowan must have felt when he found himself called upon to make editorial judgement calls coming off the back of his meetings. He operated at the cutting edge of our business when Northern Ireland seemed to be without political hope and sliding inexorably towards a level of community conflict not seen since the outbreak of the troubles.

It was a tough, demanding job which drained him, and eventually left him, in his own words, a physical and mental wreck.

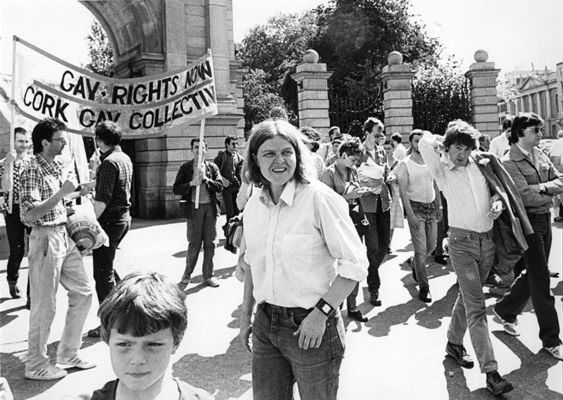

Journalist Brian Rowan

He walked away from Broadcasting House in 2005, and although he wasn’t the first BBC journalist from here to quit on his seat – a colleague declared he had enough in the aftermath of the 1987 Enniskillen Poppy Day bombing – Rowan wanted to regain some degree of normality in his life.

He thought long and hard before deciding to write this book but it gives a remarkable insight into the pressures he faced from all sides in Northern Ireland and the toll it took on his personal wellbeing.

He thrived on the adrenalin rushes, especially around the time of the 1994 IRA and loyalist paramilitary ceasefires, the Good Friday Agreement and the decommissioning process. He had a contacts book which gave him direct lines of communication with the police, military and senior government officials, and few journalists, if any, had access to the UDA and UVF like he did.

But there were stresses and low points as well. It wasn’t always straightforward and uncomplicated. For instance, his refusal to accept the IRA denial of involvement in the raid on the offices of the RUC Special Branch in Belfast on St Patrick’s Day 2002; their activities in Colombia, and involvement in what became known as “Stormontgate” did not endear him to some of those at the top of the republican leadership.

He was nobody’s fool, and he didn’t suffer fools either. MI5 tried to muzzle him and nearing the end of the negotiations which led to the Provisionals decommissioning their weapons – something they claimed they’d never do in a million years – and when the Northern Ireland Office was giving him grief, the demands he faced were enormous as he reported the comings and goings. At one stage he spoke with Martin McGuinness who told him: “If I were in your shoes, I would keep my nerve……and, at the end of this process, you will be vindicated.”

Rowan draws heavily from hundreds of documents and pages of scribbled notes which he kept. He was assiduous.

The hurried exit of Freddie Scappaticci (aka Stakeknife) he claimed, was facilitated by republicans. We still await the outcome of an investigation of what he got up go. But in the meantime Rowan recalls being told that the clinking sound of a spoon on a glass sometimes signalled the start of taped confessions by those accused of being informers before they were taken away and shot.

He was once asked by republicans to attribute one of their briefings to a DUP source in a bid to distance themselves from a story revealing that they were in secret talks with the British. It’s all there on pages 88 to 99.

There were times when he feared for the safety of himself and his family.

As well as the late David Ervine, a good and trusted friend, and a few others with close connections to the loyalist paramilitary groups – Gusty Spence, Hugh Smyth, Gary McMichael and William ‘Plum’ Smith among them – Rowan back then, genuinely believed this was a loyalist leadership which had fully embraced the developing peace process, and confident enough to move on.

He writes well of McGuinness, and the former RUC Chief Constable Ronnie Flanagan. He also remembers a few lesser known individuals who were on the fringes, one of them Roy McShane, Gerry Adams’ affable car driver to and from Stormont, who quickly got off-side after the IRA decoded the files stolen in the Castlereagh Special Branch break-in.

Like myself, Roy loved his golf, and returning home after every Irish Open Championship in places like Killarney or Mount Juliet (Kilkenny), I used to slip him – very quietly when nobody was looking – a sleeve of Titleist balls which carried the sponsor’s logo.

And did dissident republicans definitely kill Denis Donaldson? I get the impression Rowan may have his doubts about who was responsible.

He has written this book from the heart and probably found the process quite cathartic. He got a lot off his chest, but as we approach the 25th anniversary of the biggest story he or I will ever cover, it’s hard not to detect his feeling of exasperation, frustration and anger of where we’re currently at, and where we should be.

Artist Colin Davidson in conversation with Barney Rowan at Glencree Symposium in Belfast this week excellent speakers enlightened debate. really worthwhile attending. pic.twitter.com/kOPXuRpDDV

— Fergus O'Dowd (@Fergusodowd) June 29, 2022

Rowan – he didn’t tell us where his nickname Barney came from – quit his job because he’d had enough. He didn’t want to be seen and heard on television and radio anymore, and there was surprise among many of his colleagues outside Ormeau Ave., myself included, that he left and changed direction. He was a brilliant reporter – extremely diligent; highly competitive, who could be edgey at times – and who preferred to work on his own and stay ahead of the chasing pack. As an athlete who ran in his days with Willowfield Harriers before Jim McDowell offered him a job in the old Sunday News newspaper he frequently led the way.

It is such a shame that he didn’t stay on and find himself a desk in a different part of the newsroom.

But then we didn’t know the extent of his personal battle to try and maintain some sort of sanity amid all the sadness and madness that was this place back then. With a few notable exceptions who are still on the treadmill, the Belfast-based journalists of 2022 are fortunate to be mostly free of it all.

A large section of the media contingent who congregated outside Castle Buildings for the signing of the Good Friday Agreement are mostly off the stage now, living with memories of some terrible times, and in spite of the shocking lack of political advancement, relieved they’ll never happen again. And they won’t.

This is a tough read at times. The tone and content is different from the great many Troubles-related books that have gone before. It is deeply personal. This is an author free of self-pity trying to divest himself, not so much of the ghosts of the past, but those demons which, at times, made his life so miserable, especially when he was at the top of his game.

Rowan writes of himself: “This book is an explanation, not a confession. It is a walk along that thinnest of lines I have often described; those between life and death and on a path where morals, ethics and principles become blurred and our minds become tortured.

“…..the nightmares. Shouting in my sleep, trapped, surrounded. The dilemmas. The decisions. The doubts. Trying to stay strong and losing my nerve for a while; needing to escape. And how I still fall into places and moods of darkness.”

While the rest of us who worked in his era enter our late 60’s and early 70’s, maybe spending more time around the house and with the grandchildren, he continues to pop up on the airwaves now and then to provide expert analysis and comment on the various issues of the day. He’s an important, measured, insightful voice, very much in touch.

This small family to which we still belong – journalists never retire completely – should therefore be grateful he took time out to look back and reflect on the drama, and trauma, he went through; how his hugely supportive wife Val stood by him which can’t have been easy given the type of hours, and company, he kept. Some of us reporters back then made for lousy partners and he rightly, and touchingly, gives Val her place, and space, in a closing chapter.

She has the last word, but I somehow doubt if we’ve heard or seen the last of him.

Deric Henderson is the former Ireland Editor of the Press Association. He is the author of the best selling book, Let This Be Our Secret and co-edited Reporting The Troubles and Reporting The Troubles 2.

Míle buíochas @GerryAdamsSF for the Rowan. Now safely in South Armagh soil. I’ve called it Barney. pic.twitter.com/hRrexndTO1

— Conor Murphy (@conormurphysf) April 28, 2018