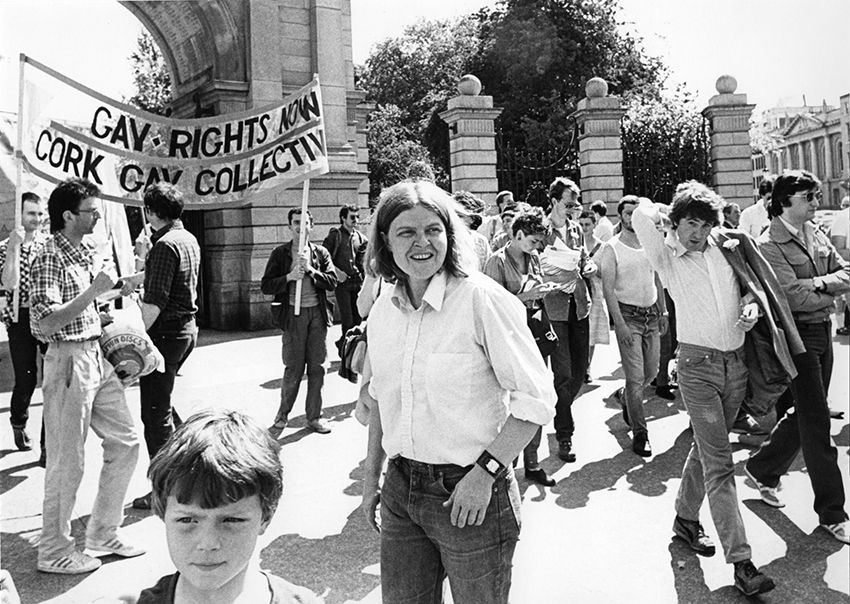

The Woman who Stole Vermeer: The True Story of Rose Dugdale and the Russborough House Art Heist by Anthony M. Amore. Pegasus €27.95. pp272

I NEVER met Rose Dugdale, but I’ll never forget how one of the men in her life kept me waiting for a fortnight.

It was October 1975 in Monasterevin, County Kildare, where Eddie Gallagher, a maverick republican from Donegal, was holding Dr Tiede Herrema, a Dutch industrialist, captive in the upstairs bedroom of a house in a council estate at St Evin’s Park.

With him was a woman from Derry, Marian Coyle. The couple headed up a gang which kidnapped Herrema near a factory he owned and then held him hostage in a hopeless effort to secure the release of Dugdale, who was serving a sentence for the theft of rare artwork.

The dull and uncommunicative Larry Wren – as he was then – who went on to become the Garda Commissioner, was the Chief Superintendent in charge of the police and military operation mounted to negotiate a peaceful end to a siege which dragged on, and on and on, and on.

Watching and waiting was hard work, and many idle hours were spent on an adjoining GAA pitch practising golf shots with lob wedges, and playing soccer against the lads from the Evening Herald. It was a 24/7 vigil, although some nights, when others deputised, usually meant giving it a lash in a hotel bar not too far away where the manager, an alcoholic, hit the drink after being overwhelmed by teams of noisy reporters from the London tabloids demanding room service and telephone lines. That’s when expense accounts really counted.

It was all fairly civilised. The late Frank Delaney, then of BBC Northern Ireland, kept us entertained with his antics chasing Garda Special Branch cars entering and leaving the estate. Jim Fahy was there for RTÉ. Mickey Sharkey (brother of the singer Fergal) and the Irish Press team pulled off a brilliant scoop when they managed to install a listening device to eavesdrop on Gallagher.

A SENSE OF OLD DECENCY

There was the occasional poker school hosted inside the Irish Independent’s caravan – the Belfast Telegraph and the Irish Times shared their own – and even amidst this fairly competitive journalistic environment there existed a sense of old decency as we looked out for each other.

Until late one afternoon after a detective was shot in the hand as he climbed a ladder at the back of the house to try and sneak a glimpse of Gallagher, Coyle and the man they bound and gagged and held captive. I’ll always remember the frantic race to reach the only public telephone to file for that evening’s final editions. Back then there were no mobiles, or high tech equipment to transmit.

The green telephone kiosk was at the entrance to the estate and the Belfast Telegraph correspondent was first to it pick up and then shout loudly into the receiver to a copy taker back in the Royal Avenue as angry rivals screamed abuse and hammered the windows and door. It was a great story to be on.

But like a few standout episodes in Dugdale’s strange career as a self-styled revolutionary, this was another doomed to failure, and by the time Gallagher and Coyle emerged with their hands in the air after 19 days inside No.1410, this was a hostage story already relegated to the inside pages as those of us on duty at the media encampment struggled to fill the notebooks.

Wren and his team, who kept us well clear of the house, had an aversion to sharing any sort of information at the daily briefing sessions close to where the journalists had set up temporary accommodation. We were starved of even the most meaningless of details. Occasionally he faced the cameras, but generally left the questions to his press officer, the hapless Tom Kelly. “What did they have for breakfast, Tom?” someone might ask to kick off the proceedings. “Sandwiches were sent in,” came the reply. “And what were the fillings? Salad? Tuna?”

“Sorry,” said Tom, catching the eye of his boss. “We can’t comment.”

Unlike Dugdale, Wren was obviously destined to go far.

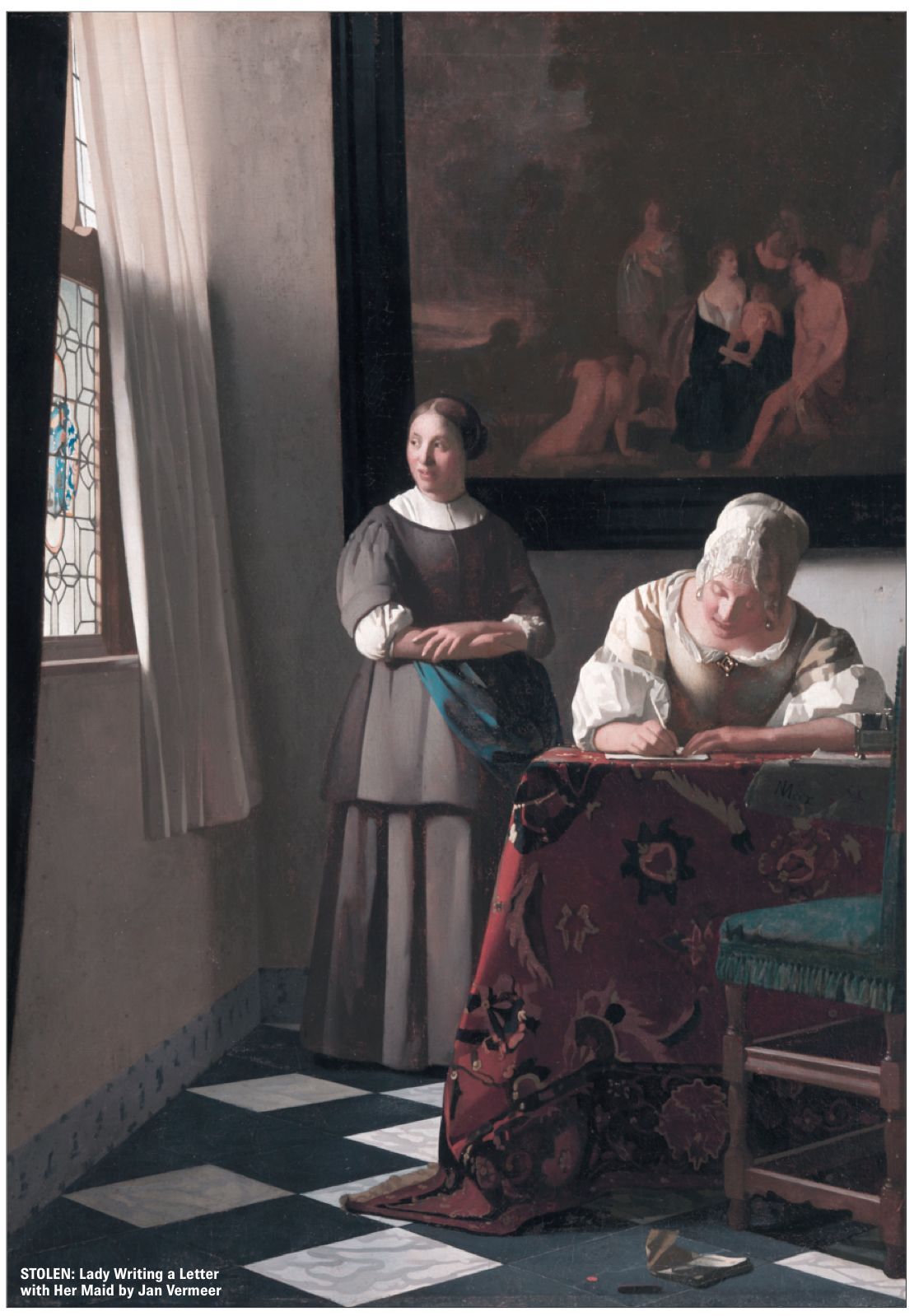

She remained in a Limerick cell for another five years, completing two thirds of a nine-year term for her role in masterminding a raid on Russborough House, County Wicklow, in 1974 to steal paintings worth an estimated £8.5m, including works by Goya, Gainsborough and Rubens, as well as Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid by the mysterious master, Johannes Vermeer.

EXTREME WEALTH AND PRIVILEGE

This was an attempt to force the British government to send back the Price sisters, Dolours and Marian, who had been jailed for their part in the bombings of the Old Bailey in London in March 1973.

In his book, The Woman Who Stole Vermeer, Anthony M. Amore, director of security and chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, details – or at least tries to detail – the career of a woman born into extreme wealth and privilege; an Oxford-trained PhD, who fell in love with Ireland, ending up flirting with some seriously hard men belonging to a movement which never really accepted her as one of their own or took her to their heart. Except for Gallagher.

The book is supposed to focus on the art heist at the home of Sir Alfred and Lady Clementine Beit, and, as someone who had been charged with ongoing efforts to recover valuable works stolen from the Boston Museum in 1990, Amore clearly knows the art business. But this is more a biography of Dugdale. And, even though the author’s grasp of the chaotic times isn’t particularly evident, he’s understandably fascinated by Dugdale, and especially her escapades.

Take the attempt to bomb a police station in January 1974 when she and Gallagher and couple of other desperadoes ordered a helicopter pilot to fly them to Strabane so that a couple of other IRA men could light the fuses and toss two milk churns filled with explosives unto the town’s RUC barracks. One fell hopelessly off-target into the River Mourne, and the second landed harmlessly in the garden of a nearby house.

Then there was the raid on Russborough House, a majestic Palladian stately pile near Blessington, County Wicklow, which happened two months later, and which ended in another failure. This time, according to the book, she was accompanied by two men from “Gallagher’s own makeshift active service unit” and within 10 minutes of overpowering Sir Alfred, his wife and their staff, they stole 19 paintings, 11 of which had been returned just days earlier from the National Gallery in Dublin where they were held for safekeeping.

The demand for £500,000 and release of the Price sisters, then on hunger strike in Brixton Prison, as well as their comrades Gerry Kelly and Hugh Feeney who were also in jail, soon followed, as did the arrest of Dugdale. She was alone at a cottage hideaway in west Cork when the police came calling. Ten days after they disappeared, all the paintings were recovered and Dugdale was in custody, pregnant with Gallagher’s child.

Dugdale had previous history for thieving art – including a raid on her parents’ home – but this was an operation by a renegade group headed by Gallagher who had become disillusioned with the IRA’s campaign at the time. How the republican leadership must have raged and cringed with embarrassment. And you can imagine their consternation when Gallagher’s go-it-alone gang seized the unsuspecting Dr Herrema, which again attracted the sort of attention which did little to enhance their cause.

MASTERMINDING RAID

Anthony M. Amore has drawn heavily from newspaper and magazine clippings, as well as TV and radio broadcasts, to write this book and I’ll leave it to him (on page 235) to explain why Dugdale, via a trusted (his words) intermediary, refused to cooperate in the preparation of it. That’s a pity because I doubt if there is much on the pages that hasn’t already appeared elsewhere. She will go down in history for masterminding the raid at Russborough House, and in Strabane and over the Lifford Bridge in Donegal they still recall that wild assault on the police station as if it happened yesterday.

But there is much more to the life and times of this individual, and her relationship with Gallagher cries out for more answers. Simple things. Was it London or Edinburgh where they first met, and was she ever sworn in as a member of the IRA? And whatever happened to their 1978 marriage while she was in Limerick four years after her son Ruairí was born? She was released two years later and Gallagher was freed in 1990.

The author writes: “They both possessed the unique sort of passion that burns in those who have, after years of searching, latched on to the perfect cause to match their zeal. They complemented each other perfectly.”

They probably did as fugitives while on the run. But did the woman who stole a Vermeer also steal his heart? How and why? It’s not the story of the art heist that intrigues me. It’s their relationship that I find so fascinating and maybe there is another book waiting to be written about Rose Dugdale and Eddie Gallagher

• Deric Henderson is the former Ireland editor of the Press Association and was a reporter with the Belfast Telegraph at the time of the siege. He spent just over a fortnight in Monastervin waiting for Herrema to be released. It was the Friday afternoon near the end of the second full week, and he felt he needed a breather. But just as he arrived back to his flat in south Belfast to switch on the teatime news, guess who also decided they’d had enough?