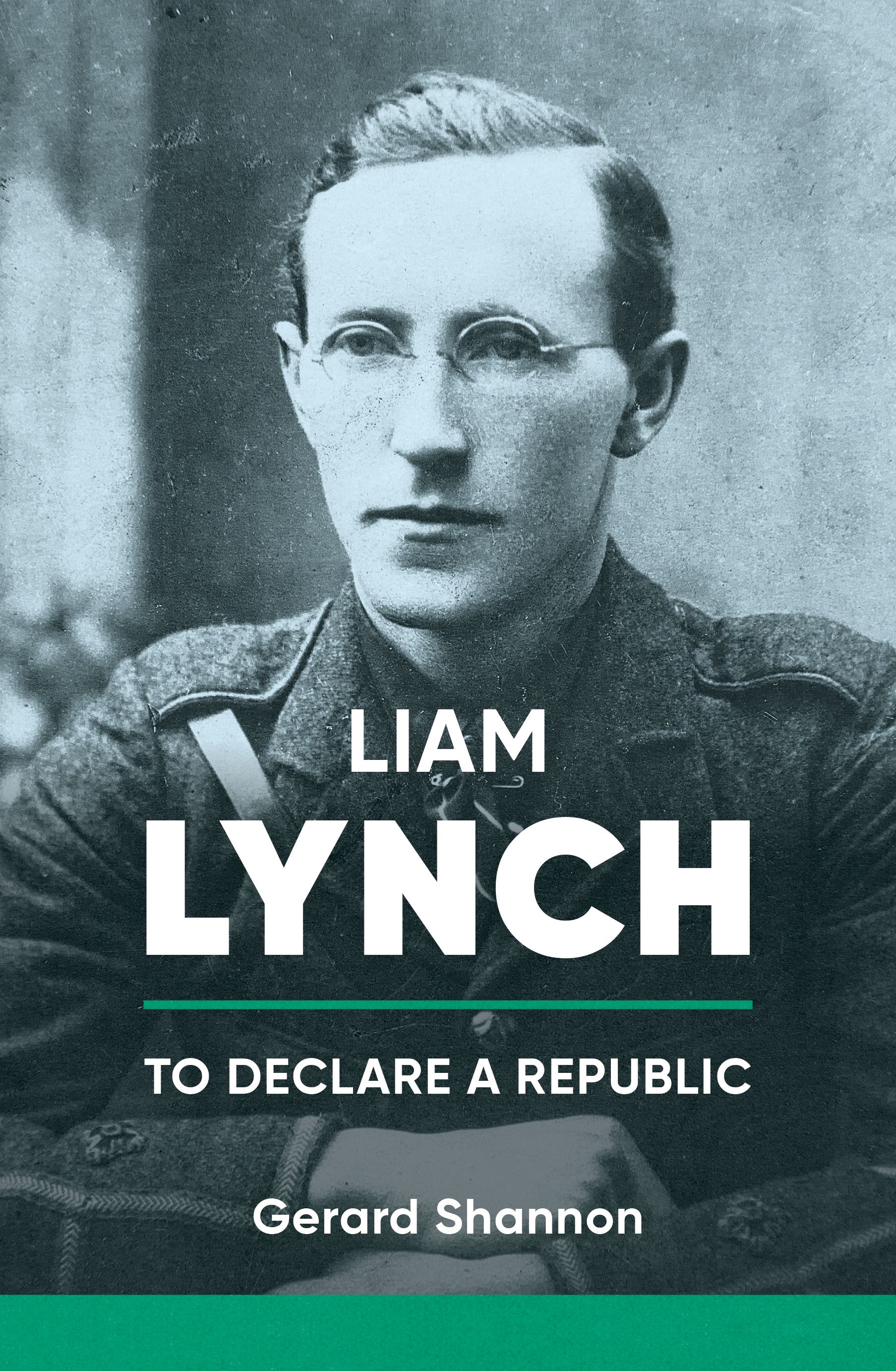

Liam Lynch: To Declare a Republic by Gerald Shannon (Merrion Press, £17.99)

NEXT month marks the centenary of the death of Liam Lynch, who, as chief of staff of the IRA, was the leader of the anti-Treaty forces. During the civil war, which he had sought to prevent happening, he was shot, during a skirmish, by an unknown member of the Free State soldiery.

By that time, the 30-year-old had won a reputation as a courageous guerrilla fighter with a single-minded desire to bring about the creation of a 32-county Irish republic.

Lynch, as with so many republican heroes, has suffered from revisionist historians who have cast him as an intransigent who prolonged the war with the Free Staters.

That myth is destroyed by Gerald Shannon’s long-awaited biography. The nuanced portrait of Lynch that emerges from the author’s meticulous research is of a man struggling to resolve conflict with his former comrades rather than exacerbate it.

Shannon presents us with a serious young man who was anything but as ruthless as the anti-republican nay-sayers have suggested. The tall, bespectacled Lynch was quiet, earnest, polite and, evidently, always smartly dressed.

Born in 1892 in Anglesboro, in the south eastern area of Co Limerick that is close to the border with Co Cork, Lynch was 17 when he took an apprenticeship in a hardware store and joined the Gaelic League. He moved on to work in a timber yard in Fermoy.

It was there, in the aftermath of the Easter Rising, that he witnessed four brothers, two of them barefoot and handcuffed, being paraded through the main street after their arrest by the Royal Irish Constabulary. This humiliating sight turned the nationalist Lynch into a republican. He joined both the Irish Volunteers, in which he was soon elected to First Lieutenant, and the IRB.

By the time of the Tan War, Lynch had been appointed as commandant of the IRA’s Cork No. 2 Brigade. In that role, he organised and led several operations against the British forces, notably an arms raid in Fermoy – during which he was wounded – and the kidnapping of a British army general.

His dedication to the cause was famously expressed in a letter to his brother, Tom, in November 1917: “We have declared for an Irish Republic and we will not live under any other law.” He never deviated from that viewpoint in the following six years of his life.

By the time of the Tan War, Lynch had been appointed as commandant of the IRA’s Cork No. 2 Brigade. In that role, he organised and led several operations against the British forces, notably an arms raid in Fermoy – during which he was wounded – and the kidnapping of a British army general.

In those years, he won the respect of the IRA’s Chief of Staff, Richard Mulcahy, and its Director of Intelligence, Michael Collins. Mulcahy, who would later clash with Lynch when they took opposing sides in the Civil War, regarded him as the most competent, reliable and inspiring of leaders, referring to him as “a lion of resistance". He offered Lynch promotion to general headquarters, but he turned it down because he wished to stay with his troops in Cork.

Some more signed books of 'Liam Lynch: To Declare a Republic' now in @easons on O'Connell Street! All very exciting. pic.twitter.com/wMEEQDpCmY

— Gerard Shannon (@gerry_shannon) March 3, 2023

Instead, he was appointed Commandant of the First Southern Division in April 1921, becoming responsible for leading more than the 30,000 men and women in brigades in Cork, Kerry, Waterford and Limerick, and making him “the most influential IRA leader outside GHQ.”

Throughout the debates over the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Lynch remained consistently opposed to its provisions in the firm belief that it amounted to a betrayal. Initially, he made a valiant effort to forge some kind of compromise with his former comrades.

Once it became clear that a rapprochement was out of the question, most obviously when the Free State army shelled the anti-Treaty forces garrisoned in Dublin’s Four Courts in June 1922, he accepted that he must fight, and fight fiercely, for his republican beliefs.

All this is a pity, it never should have happened. I’m glad now I’m going from it all. Poor Ireland, poor Ireland!

He was the natural choice as the anti-Treaty IRA’s chief of staff, but Shannon argues that, despite his military skills, his leadership was flawed. He lacked a strategic vision; he took no interest whatsoever in politics; and he failed to build alliances, turning his back, for instance, on organised labour. Unsympathetic to trade union activism, he believed it was antagonistic to nationalist demands.

However, Lynch’s considerable responsibilities and the consistent pressure from the Free State army left him little time to consider matters beyond the boundaries of the southern counties. One of the most fascinating passages in the book concerns the shooting of Collins at Béal na mBláth by troops Lynch commanded .

He congratulated the men involved, regarding it as “a most successful operation”. But, in a letter to his close confidant who led the ambush, Liam Deasy, he betrayed his ambivalence about the killing of a man he had long esteemed.

“Nothing,” he wrote, “could bring home more forcibly the awful unfortunate national situation at present than the fact it has become necessary for… former comrades to shoot men such as M. Collins who rendered such splendid service to Republic in the late war against England.”

The other figure who haunts the story is Éamon de Valera, who, as head of the anti-Treaty side, was nominally Lynch’s boss. The pair could not have been more different, and the tension between them crackles as the politically adept de Valera inches towards negotiating some kind of truce in opposition to Lynch.

What will be one of the books of the year from us , just released from @MerrionPress , comes Liam Lynch : To Declare a Republic - the first modern biography from @gerry_shannon . Copies available now at https://t.co/WWS3qFogbI €20 with delivery included pic.twitter.com/XmHAKeWPOE

— TheBookshop.ie (@TheBookshopIE) March 1, 2023

At an IRA executive meeting in March 1923, a motion calling for an end to the war was defeated by six votes to five, with Lynch casting the decisive vote against. As far as Lynch was concerned it was the army’s job “to hew the way to freedom for politics to follow”.

Another meeting was to be held three weeks later, but Lynch died beforehand. He was fatally wounded when he and his comrades were fired on by a Free State search party in the Knockmealdown mountains. For a moment, they thought Lynch was de Valera.

Shannon records the sympathetic treatment shown to Lynch by one of the pro-Treaty soldiers, Lieutenant Laurence Clancy, who was sobbing when he heard Lynch’s final words: “All this is a pity, it never should have happened. I’m glad now I’m going from it all. Poor Ireland, poor Ireland!

A pity indeed. Clancy and Lynch, who had fought on the same side against the British, found themselves as enemies due to their differing responses to that damned treaty imposed by Britain. Yet, as Lynch lay dying, Clancy appreciated he was tending to an Irish hero. Which, rightly, is how he has been remembered ever since.