Heroes of Ireland’s Great Hunger by Christine Kinealy, Jason King and Gerard Moran (Quinnipiac University Press, £21.95)

It was several years after the Holocaust that we discovered the secret heroes who risked their lives to help Jews avoid capture by the Nazis. Now, 170 years after the Great Hunger, comes a book recording the achievements of people who were willing to sacrifice their lives to help the starving, powerless poor of Ireland.

They are a diverse group, ranging from kindly landlords to pioneering doctors. They include visitors to these shores – among them, Quaker philanthropists, a Polish explorer and an American missionary – and others for whom Ireland was a country far across the ocean, such as native Americans and Canadian nuns. What linked them was their compassionate response to an unspeakable tragedy.

Page upon page, story upon story, this is an uplifting anthology of altruism. The British government may have abandoned millions of people it regarded as its citizens to their fate, but, amid death and disease, here were individuals who refused to turn their backs. No laissez-faire for them. Rejecting the principles of political economy, they chose the principles of humanitarianism.

Although historians of An Gorta Mór have known about some of these good Samaritans for years, their contributions have not been accorded the recognition they undoubtedly deserve. James Hack Tuke is an excellent example. His writings have proved to be valuable source material for academic studies, but his efforts on behalf of the victims of what should be known as the “fake famine” cry out for broader public attention.

The Kindred Spirits Monument acknowledges Ireland's gratitude to the Choctaw Nation for their help during the Great Hunger of 1847. The Choctaw bestowed a blessing not only on the starving men, women & children of Ireland, but on the whole of humanity.#Cork #Choctaw #Ireland pic.twitter.com/zdcMMenE2i

— Mark Loughrey (@mark_loughrey) July 9, 2020

Tuke, an English Quaker, offered practical help by distributing free food in towns in Connaught and Ulster. Aside from arranging such welcome short-term relief, it was his eye-witness testimony of the effects of the potato blight during the winter of 1846 and into the summer of 1847 – Black 47 – and the callous reaction of the authorities that, in the long-term, have proved so eye-opening. He told truth to power. But power, as we know, turned a deaf ear.

WRETCHEDNESS ALMOST BEYOND BELIEF

In Dunfanaghy, Co Donegal, where he visited “a number of the poorest hovels”, he wrote: “Their appearance, and the condition of the inmates, presented scenes of poverty and wretchedness almost beyond belief. One dirty cabin - not more than twelve feet square - contained several persons. Two or three of them were full-grown men - gaunt and hunger-stricken - willing and wishful to obtain work, but unable. The mothers, crouching over a few embers of turf… looked misery itself.” Moving on to the Glenties workhouse, he told of “the living and the dying stretched side by side” on “dirty straw.”

Tuke, just 26 years old on his first visit, returned to Ireland in 1880 at another period of crisis: the so-called “forgotten famine.” This time, he raised money for relief and also addressed the structural problems, advocating emigration as a solution. No wonder he has been accorded the opening chapter, for here was a man who surely merited description as “Ireland’s greatest benefactor” and its “unsung hero.”

'The Great Hunger' from the Quaker tapestry. pic.twitter.com/NFL6qd95HF

— Quaker George Fox (@GeorgeFoxFriend) September 6, 2015

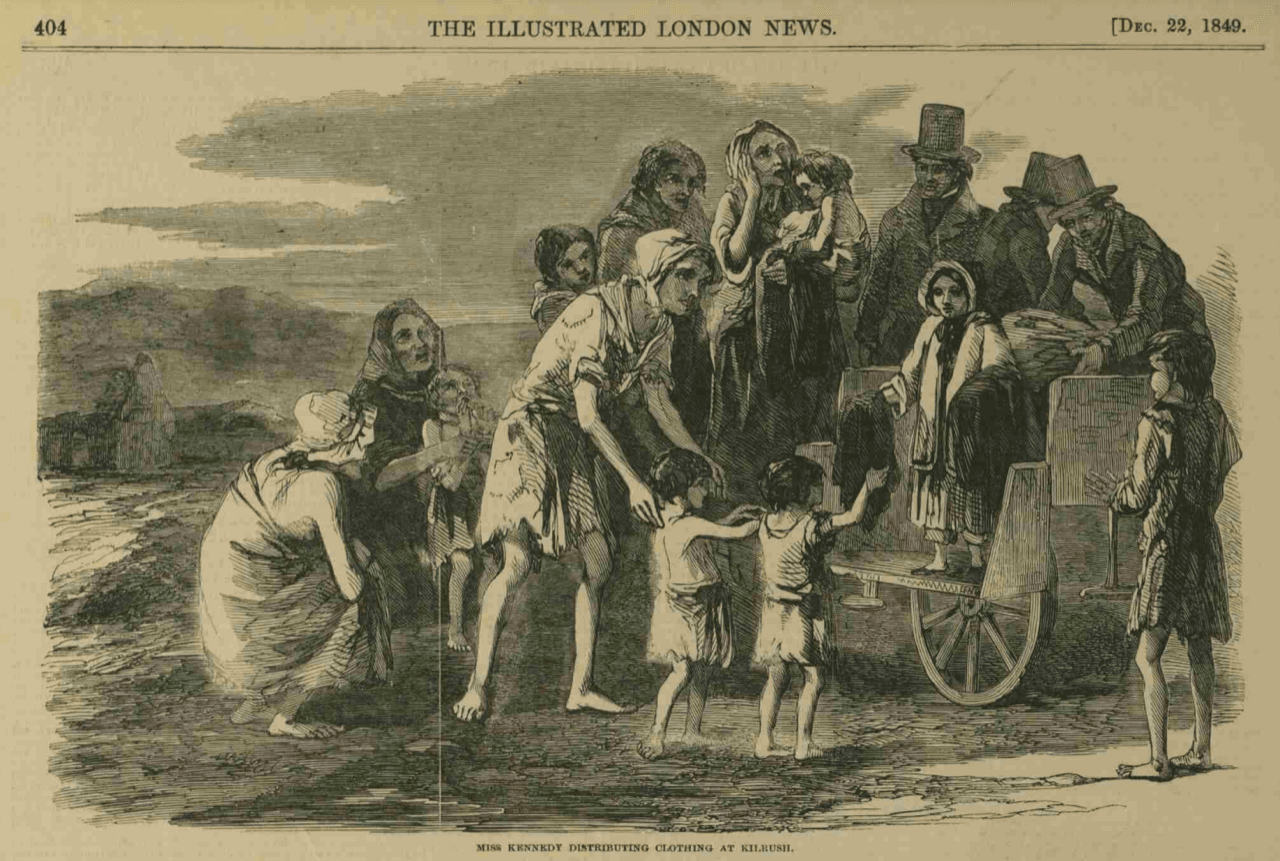

So, in choosing Tuke as one of their heroes, the editors were hardly going out on a limb. His was a straightforward case of philanthropy. By contrast, their selection of Captain Arthur Edward Kennedy, a poor law inspector in Kilrush, Co Clare, is more nuanced because a potential villain turned into a hero. As a product of his class – son of a Co Down landlord and career officer in the British army – he treated his well-remunerated appointment by the Irish poor law commissioners as one might have expected.

His earliest reports, which recorded his bureaucratic re-organisation of the workhouse on more efficient lines, show him to have been insensitive and blind to the human misery around him. He was given to describing the local people in “contemptuous terms” and showed no sympathy for those evicted from their homes. According to the chapter’s author, Ciarán Ó Murchadha, Kennedy’s “apparent failures of discernment… suggested a pre-existing prejudice with a pronounced hostility towards the poor.”

SAVING HUNDREDS OF LIVES

By March 1848, however, some four months after his arrival, there was a marked change of attitude and approach. He was being praised in newspapers for his “exertions” on behalf of “suffering humanity”. He gave money to evicted tenants; he risked his own health by visiting fever hospitals; he rescued homeless families from the roadside; he was credited with saving hundreds of lives.

In the process, Kennedy achieved a measure of fame because of a sketch in the Illustrated London News (above) which showed his seven-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, distributing clothes to the needy in Kilrush. (A section is reproduced on the cover of the book and it was drawn by James Mahony whose images of the Great Hunger rightly earn him a chapter in Heroes too). Behind the scenes, Kennedy was being undermined by the owner of Kilrush, and 20,000 acres, Colonel Crofton Moore Vandeleur. He eventually succeeded in having his troublesome inspector removed from his post.

Many thousands of native Americans died of disease and starvation during their forcible removal from their homelands to an area known as Indian territory. Yet, just 16 years after this journey, known as the Trail of Tears, the tribe collected money for victims of the Great Hunger. The poignant Choctaw gift of $170 is a remarkable tribute to the international solidarity of the dispossessed.

Not all landowners were as heartless as Vandeleur. Many, more than myth has long suggested, behaved well. The authors have lighted upon the second Marchioness of Sligo as their example of landlord beneficence and their choice is warranted by her efforts – and those of her son – on behalf of the poor in Westport. They supplied their tenants with food, clothing, and blankets.

Landlordism was an undoubted scourge in Ireland and, at this end of history’s telescope, we can see how the Great Hunger which killed at least one million Irish people also sounded the death knell to the system of landownership. But individual landlords, especially those who were resident, did what they could to alleviate distress.

ROLE OF ELITES FORGOTTEN

As the authors note, “the role of Irish elites who did come to the aid of their poorer fellow country men and women is sometimes forgotten.” They mention only in passing Sir James Dombrain, English-born inspector general of the coastguard, who would surely have merited a chapter of his own because of his influence on landlords in Donegal, particularly Lord George Hill, who he introduced to the county.

Dombrain, hero of a lacerating Swiftian poem by Seamus Heaney, insisted in the face of hostility from the authorities in Westminster and Dublin on distributing grain for free to “famine” victims in Mayo and Donegal. He and Hill, who owned 23,000 acres of Gweedore, worked in tandem to provide relief. As a result, no-one died from starvation on Hill’s estates.

SOLIDARITY OF THE DISPOSSESSED: Chief Gary Batton of the Choctaw Nation meets Traveller James Collins during a 2017 visit to Ireland to reignite the transatlantic Famine links. (rolfingnews.ie)

One chapter bound to catch the imagination of readers is devoted to the contribution of the Choctaw Nation. In 1831, many thousands of native Americans died of disease and starvation during their forcible removal from their homelands to an area known as Indian territory. Yet, just 16 years after this journey, known as the Trail of Tears, the tribe collected money for victims of the Great Hunger. The poignant Choctaw gift of $170 is a remarkable tribute to the international solidarity of the dispossessed.

Finally, a mention of one of the authors, Christine Kinealy, who must surely deserve to be called the Great Hunger’s academic hero. Her body of work on the subject over the past 35 years has been remarkable for its quantity and quality. As founding director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute, at Quinnipac University in Connecticut, she continues, as this book illustrates, to shine a light on a national tragedy that, for too long, remained in darkness.

Heroes of Ireland's Great Hunger can be ordered online from Cork University Press and is available at An Ceathrú Póilí bookshop in An Chultúrlann.