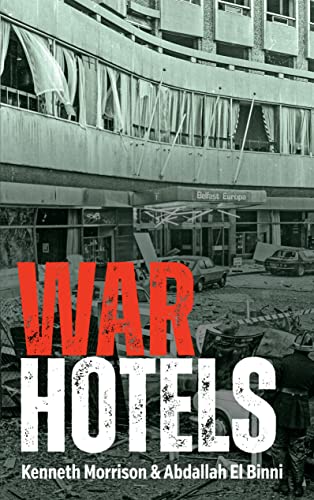

A new book, War Hotels by Kenneth Morrison & Abdallah El Binni, examines the role of landmark hotels in war-torn cities. In this extract the authors focus on IRA bombings of the Europa Hotel in Belfast during the 1970s

WHEN there were events to report on, the Europa would be packed – but there would be occasions on which the press corps would be smaller in number. They would, of course, return when events on the ground required their presence.

9 December 1973, the Sunningdale Agreement (so-called because negotiations commenced at Sunningdale Park Hotel in Berkshire) was signed. It envisaged both a power-sharing executive in Northern Ireland and a cross-border ‘Council of Ireland’. The unionist response was overwhelmingly negative and, in an effort to overturn the agreement, a general strike was called by the Ulster Workers’ Council (UWC) in protest at the agreement brokered by the British government. Roadblocks established by the UWC essentially brought Belfast to a halt. The Europa was full once again, though supplies were short. Dinner and drinks had to be served by candlelight and, in order to provide hot food for the guests, a barbecue was set up at the side of the hotel.

The Europa had not been subject to attack for some time, but on 3 May 1974 an armed IRA gang entered the hotel and planted two bombs – one in the lift shaft and one in the top-floor water tower. Both were defused. One and a half months later, on 18 June, a bomb detonated next to the nearby Grand Opera House, and the following day another IRA bomb was detonated on Great Victoria Street, causing significant damage to the hotel. The attacks continued throughout July and August 1974, with two large car bombs destroying almost every window in the hotel.

Remarkably, however, no one was killed in the grounds of the Europa as a result of IRA bombs – a fact that the hotel management did their best to emphasise.

The 25 July bombing of the Europa, part of an IRA plan to breach British Army security and to bring traffic and trade in Belfast city centre to a standstill, was particularly destructive. A bomb was transported in a glazier’s van that had been hijacked by IRA operatives. The elderly driver was instructed that his passenger would be held hostage until the device had been driven to the security entrance to the hotel, which it duly was. Thereafter, a British Army bomb-disposal unit attempted to detonate it in a controlled explosion but were, on this occasion, unsuccessful. The bomb detonated, shattering most of the windows on the lower floors of the hotel.

50 YEARS OF THE EUROPA HOTELJames McGinn, General Manager of the Europa Hotel is joined by colleagues Callum Dickson, Martin Mulholland, Lynsey Monaghan, Kyle Greer and Aine Finnegan as the world-famous hotel unveils a permanent lobby installation to celebrate its 50th birthday! pic.twitter.com/75svacs0ej

— Europa Hotel Belfast (@europahotel) October 28, 2021

Remarkably, however, no one was killed in the grounds of the Europa as a result of IRA bombs – a fact that the hotel management did their best to emphasise. In an interview with the Irish magazine The People (their correspondent claiming that [Harper] Brown ‘runs the Europa more like a command post than a hotel’) in the wake of the July attacks, Brown defiantly stated, ‘We haven’t lost a guest yet ... we’re proud of that.’ But being a central figure in the drama of the Europa was not without risks. Brown’s endeavours, while undoubtedly well received by his guests and the Belfast business community, led, allegedly, to his name being placed on an IRA death list, and some of his closest associates had to leave the Europa and Belfast – such as the head hall porter, Tommy Dunne, when, on the basis that he had given too much information to a journalist, he was threatened by the UDA.

According to an RUC report, armed IRA operatives carried a suitcase ‘containing an estimated 25–30lb bomb into the hotel and left it in the lift shaft in the foyer’ before escaping in a car that was waiting outside.

Matters worsened throughout 1975, with the first major attack on the hotel taking place on 23 January. According to an RUC report, armed IRA operatives carried a suitcase ‘containing an estimated 25–30lb bomb into the hotel and left it in the lift shaft in the foyer’ before escaping in a car that was waiting outside. The hotel was immediately evacuated but just after noon the bomb detonated, ‘causing extensive structural damage to the ground floor area of the hotel’. The lift shaft, the foyer and the ground-floor Whip and Saddle bar were severely damaged and the windows on the first two floors were blown out.

Yet the hotel remained operational, with staff and management endeavouring to continue as if the situation was normal. The glaziers, possibly the most successful tradesmen in Belfast, were once again brought in to replace the shattered window panes and warped window frames. Another large bomb, detonated on Great Victoria Street on 1 December 1975, did more serious damage, however. The front entrance of the Europa was badly damaged, the lift shaft buckled and the second and third floors were almost completely destroyed. As a consequence, the hotel was forced to close for more than a year.

Security was subsequently the order of the day, and by the time the hotel had reopened ‘Fortress Europa’ was surrounded by barricades and barbed wire to stop unidentified cars driving up to the front entrance. Security inside the building was also tightened, with guests frequently being subject to body searches upon entering the hotel.

The British Army would, from time to time (particularly when there was intelligence about a possible attack on the hotel), place armed covert teams within the premises. They set up an observation post with darkened glass above the hotel reception, which overlooked the lobby and the front door. Other members sat about the lobby and bars looking like businessmen, with weapons concealed in briefcases; their presence was particularly noticeable (to the educated eye) when VIPs were visiting the Europa.

War Hotels is published by Merrion Press, priced £14.99.