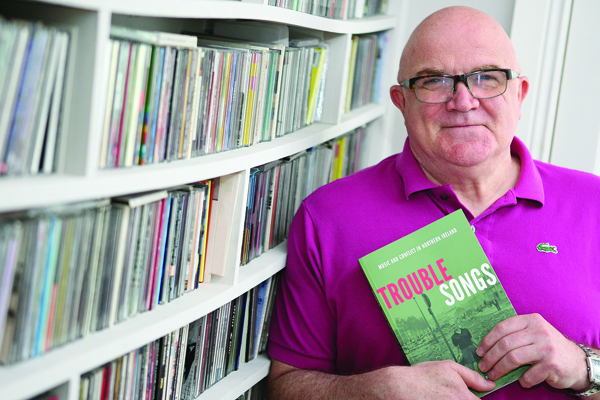

AMONG the reams of vinyl and shelves upon shelves of CDs that fill his home, music journalist and broadcaster Stuart Bailie tells this reporter how his newly published book Trouble Songs Music and Conflict in Northern Ireland reveals many untold histories.

The book charts among others the beginnings of Stiff Little Fingers, The Outcasts, the horror of the Miami Showband Massacre, the music that reverberated during the hunger strikes, The Men behind The Wire and the historic ‘Yes’ gig with Bono, Ash, John Hume and David Trimble.

“I started talking about writing a book about four years ago,” explained Stuart. “I footered about with the idea for a long time and about a year and a half ago thought it was do or die time – I really have to get this done, I can’t be boring friends and family anymore,” he laughed.

“People came forward with financial help, I started working 12-hour days, not going out and slowly it all started coming together and I was cooking on gas.

“I had a target of getting the book out to coincide with the anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement. The response so far has been very positive; people are starting to digest it now.

“A lot of people are saying that they had forgotten how bad it was, about how brave the musicians were that decided to come over and play here, to read about just how many songs that there were, that relate to the conflict, it’s a huge deal,” he said.

Stuart details in the tome how he encountered several fellow “Belfast exiles”, namely Bap Kennedy and Joby Fox across the water during the late 1980’s when the two were in Energy Orchard.

“I remember being in London and in a bar called the New Pegasus, I think it was owned by Chas and Dave. I met Bap, I met Joby, and on and off, over the years with Joby I always figured he had a story to tell that hadn’t been told. So we sat down around six months ago and a lot of what Joby had to say came out, poured out, from him being a recreational rioter, ‘clodding bricks at the army near the bottom of Fruithill Park’ to his relief work.

“The big problem for me was how to finish this book. You can’t be happy clappy, you can’t say that’s it, we’re done, everything is beautiful but I didn’t want to be pessimistic either. I think Joby – and it’s his story that concludes the book – is just an individual example of something beautiful that has happened in terms of personal change.

“What he did in Lesbos in terms of trying to help refugees, setting up the Mo Chara relief boat, if everybody was like Joby then we would be there, we’d be in the promised land.

“As I was talking to him I just thought that his work in later years was the ending to the book and that was a real delight.”

Stuart spoke of how he personally hand delivered the book to Joby’s Riverdale home.

“I arrived around 10pm at night and Joby was like ‘you’re like Fr Christmas arriving,’ and he was very pleased. We did a thing for the Four Corners Festival around post conflict and talked about the evolution of the song Belfast and the extra verse that Joby had put in. We did that, talked about it and Ursula Burns the harpist also performed. There has been vague talk of how we can take that on tour, it was really something special but I don’t know if it will work or not, but that’s the idea.”

I asked Stuart his thoughts on youth culture in 2018, and does music have the same ferocity of message. He replied that Derry “is the angry city at the minute”.

“When I was young you had a new youth culture every three years. There is a band from Derry called Touts and they are really angry, they have a song called Political People which is all about how they are unhappy with the political system, I think it’s the best song about what youth should be thinking about. In terms of LGBT music, you have Susie Blue, again from Derry and her song People Like Us details being exiled in your own area as there is no marriage equality. I grew up with the Clash, the great punk era; young people were given a voice. We’re all waiting for the statements again.”

The former CEO of Cathedral Quarter’s Oh Yeah Centre, Stuart recalled how while writing and teaching journalism at the Belfast Met he was “pulled off the subs bench” to compere the historic 1997 ‘Yes’ gig at the Waterfront Hall.

“I remember bringing 20 students with me to the press conference with David Trimble and Ash, a former student, and former North Belfast News Editor Maria McCourt, walked up to Trimble at the time and nailed him to the wall. Seeing the coverage the next day was phenomenal.”

Stuart said that a sequel to the book could be in the works, as he would like to write and expand more on the dance and rave culture scene in the north.

“I’ve lived most of the my life as a freelancer, I’m used to the uncertainty. It’s hard to make a living as a journalist, there isn’t the respect there used to be, there isn’t the pay, music journalism is considered something the kids do for free. The building the Oh Yeah is housed in used to belong to Billy McBurney, the guy who put out the Men Behind The Wire. His parents Patrick and Bridget had founded the Premier Records shop in Smithfield Market back in 1926. We met him a bunch of times, a lovely man, at the time for the centre we just had this mad idea and he came in and sussed us out in a very instinctive way. The Men Behind The Wire went to the top of the Irish charts in 1972, it fell off when Paul McCartney’s Give Ireland Back To The Irish was number one and then Men Behind The Wire went back to number one following Bloody Sunday.

“People bought a piece of plastic and they played it.

“With the book I thought this could be me signing off or the start of something, it’s definitely a bit of a milestone.”

Trouble Songs Music and Conflict in Northern Ireland is priced at £14.99 and available from Waterstones, Visit Belfast Centre, No Alibis and Eastside Arts Visitors Centre.

Clash of guitars and conflict in the north

Stuart Baille with his new book, Trouble Songs.