THE IRISH King of New Mexico died 170 years ago in Contra Costa County, California, and you’ve probably never heard of him.

The King in question was an Irishman named James Kirker from the tiny village of Killead, near Crumlin, not far from Belfast International Airport.

Kirker’s life was controversial, and he is remembered as much for his bloody deeds as he was for his scouting and trapping feats. In Kirker’s storied life he practised many professions, most of them unseemly, from pirate, trapper, mountain man, mercenary, soldier, outlaw, explorer and scalphunter.

Born into poverty in 1793 in Killead, Kirker remained there until the age of 16 when he fled to New York City to avoid being forced into serving in the British Navy. The Navy would frequently press-gang young men by knocking them unconscious, after which they woke up at sea aboard a ship and were forced to serve for years in poor conditions.

In New York he joined the privateer ship the ‘Black Joke’ and was part of the crew which plundered British vessels up and down the South American coast before being caught by the British vessel ‘Lion’ in 1813 at the age of 20. He was then part of an exchange for British prisoners captured by the Americans aboard the ‘Java’ and returned to the US.

By 1822 he was in the Midwest, making his living as a fur trapper and mountain man under the protection of General Ashley and Major Henry (Major Henry was notably played recently by Irish actor Domhnall Gleeson in the 2015 film ‘The Revenant’ starring Leonardo DiCaprio). Kirker’s comrades at the time were legendary mountain men such as Jim Bridger, John Joel Glanton, Hugh Glass and Kit Carson, who worked for Kirker when he ran his illegal mining and trapping business in Mexico.

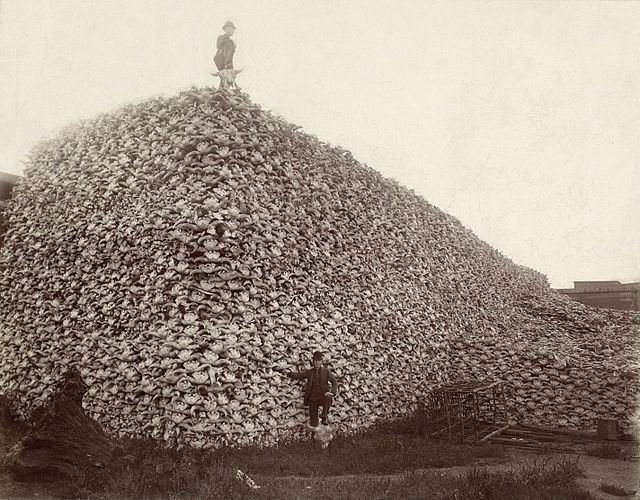

After General Ashley suffered a rout by the Arikara Nation, Kirker left the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and headed to Mexico. There he established himself as a smuggler and illegal fur trapper, particularly in the trade of buffalo pelts, using the Santa Rita mines near Santa Fe as a base. Kirker and his band also mined copper there, as well as using it as a place to store the pelts. It was near Santa Fe, then a Mexican territory, that Kirker had his first dealing with the Apache Nation.

DEVASTATION: After a buffalo hunt. In 1800 there were upwards of 60 million buffalo in the USA, by 1889 there numbered only 541. Kirker, and men like him killed them in their thousands to sell the pelts.

He acted as a fence for goods Apaches had taken in raids in Mexico and ran the booty over the border to sell in Texas and Louisiana. For his role in facilitating trade with the Apache, they named him a war chief, giving him the title ‘Don Santiago Querque’, and he soon became fluent in Spanish and Native American languages.

Kirker soon fell afoul of the Mexican government when the officials he received protection from were removed from their posts and he was declared an outlaw by the government. However the Mexican authorities soon found themselves overwhelmed by raids from Apache warriors, and the bounty on Kirker’s head was rescinded. He was invited back and given leave to raise an force to hunt Apache, owing to his knowledge of their language and trade routes.

Kirker teamed up with a Shawnee chief named Spybuck and raised a company of men around 200 strong including Native Americans from the Pawnee and Delaware Nations. Amongst Kirker’s men were escaped slaves from the American South, Mexicans and a number of Irishmen and Germans who had been prospecting for gold in northern Mexico.

In 1838 he led his band in the slaughter of around 60 Apache, scalping those they killed and selling the grisly bounties to the Governor of Chihuahua state, who paid $100 for the scalps of men, $50 for women and $25 for children.

Kirker’s next engagement took place in the Taos Valley when his men baited Apache warriors and ambushed them, taking over 50 scalps, including some scalps from those still living.

But worse was to come and history has remembered the next actions of Kirker and his band of murderers as being his most vile. After tracking Apache scouts for weeks his band encountered a village of nearly a thousand. Although the chief, the famous Cochise, and much of the village escaped, Kirker’s men slaughtered nearly 200 people. An example of his ruthlessness is shown in how during the encounter, Kirker's Mexican guide was wounded and instead of being treated was scalped and added to the grisly pile of trophies.

Returning to Chihuahua, Kirker was enraged to discover the governor only had $2000 in the treasury, which was less than what he felt his men were owed. Rumours abounded that Kirker and his men had also been massacring Mexican villages and selling the scalps off as those of the Apache. This practice would later be carried out by the notorious scalphunter John Joel Glanton, whose bloody deeds were fictionalised in Cormac McCarthy’s epic novel ‘Blood Meridian’.

After ransacking Chihuahua City and looting what they thought they were owed, Kirker’s gang fought a running battle with Mexican troops sent to pursue them. The Mexicans fell prey to an ambush set by Kirker, after which he continued North to Ciudad Juárez. Along the way his men murdered 160 more Apaches, but when Mexican officials still could not pay and the US declared war on Mexico, Kirker and his band sold military information to the US force and he was again declared an outlaw in Mexico, with a $10,000 reward offered for him.

Serving as a scout under Colonel Doniphan, Kirker continued in his role as an Apache hunter, and in 1846 his band slaughtered 130 Chiricahua Apaches, though Kirker himself boasted the number was far higher. The band initially tricked the tribe by offering them a feast before the killing began.

Due to his infamous reputation around the border lands, Kirker’s men and enemies began referring to him as ‘Rey de Nuevo México’ – ‘King of New Mexico’.

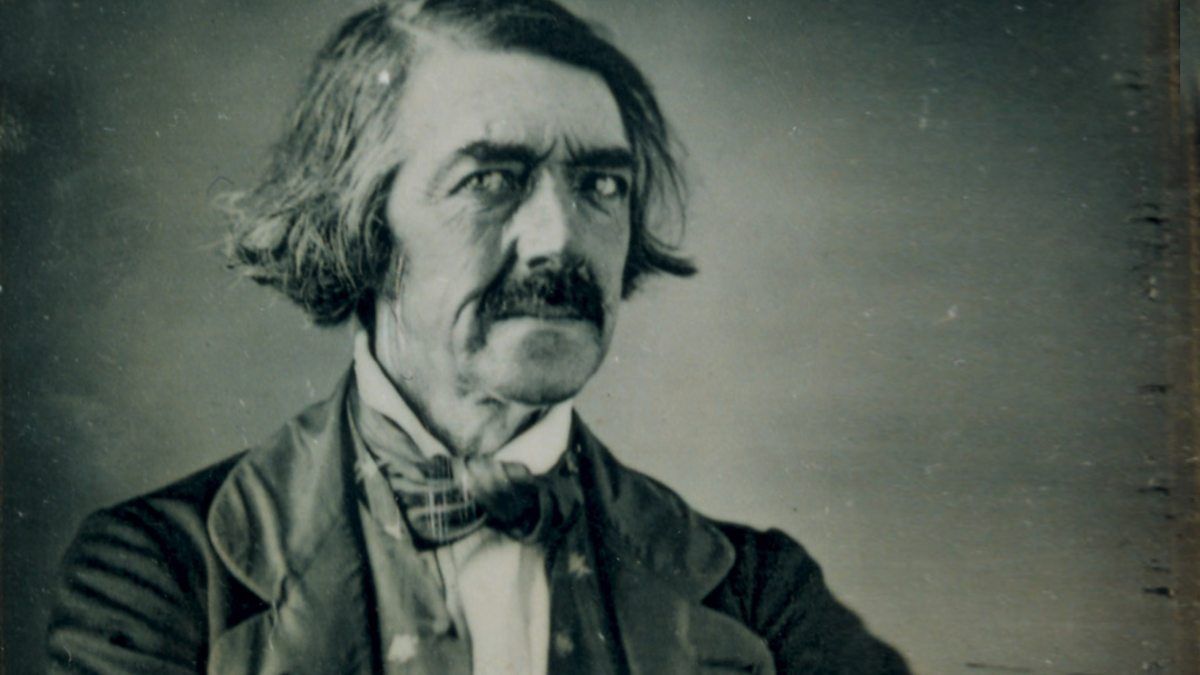

An image of James Kirker from an exhibition in 1883 in Santa Fe

After the Mexican-American war, Kirker took up escorting parties to California in the 1849 Gold Rush, and abandoning his charges in Santa Fe headed to California himself where he settled in Contra Costa County where he lived as a rancher before dying of natural causes in 1852.

Kirker’s life and deeds have been viewed through many lenses. In his day he was praised as a fearless soldier and explorer, however these days history shows him as a ruthless killer and remorseless bandit, and calls have been made in California to change the names of Kirker Pass and Kirker Creek due to his brutal and unforgivable crimes against Native Americans.

Some accounts say James Kirker, the namesake of the major Contra Costa County roadway, was a "scalp hunter" who killed women and children. https://t.co/eyAUdNBYeG

— Danville Patch (@DanvillePatch) February 24, 2022

These days, Kirker is almost completely forgotten in the country of his birth, and you’d be hard pressed to find someone who has heard of him. Perhaps that's for the best, considering his infamy, but next time you’re on your way to the International Airport, you can tell your family and friends the infamous border bandit, the King of New Mexico, once lived there.