THIS could have been the year the British state came to an end.

But it won’t be. A second independence referendum for Scotland – scheduled for October of 2023 – has been kyboshed by the UK’s most senior judges.

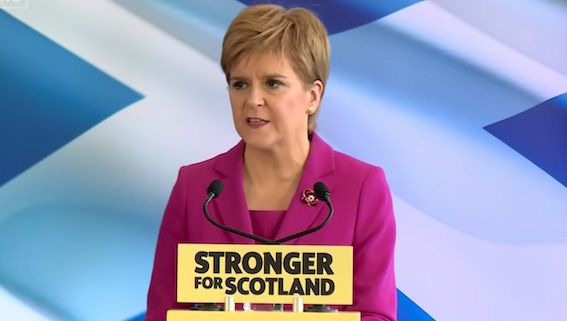

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and her SNP were officially outraged by the Supreme Court’s November ruling, which said Scottish authorities had no right to hold a plebiscite on self-determination without permission from London.

Nationalists have spent the last two months telling everybody this decision means Scotland’s union with England is no longer “voluntary”. Their opponents scoff at this characterisation of the UK, saying it is unfair. The first “indyref”, they point out, was just eight years ago.

Yet nationalist rhetoric seems to be working. Before judges cancelled indyref2 most polls showed independence and union in something close to a dead heat. If anything, supporters of staying in the UK just shaded it.

Now the dial of public opinion has shifted slightly but decisively in the other direction. Yes – a flurry of polls in November and December showed – has pulled ahead of No. If only just.

I am, like a lot of reporters, a bit of a cynic. So I suspect it is just a bit easier to support independence when there is no prospect of an imminent vote. And I also think there will be some senior nationalists – who tend to be pretty pragmatic – who are relieved they will not have to fight a referendum in 2023. Why? Because they might have lost.

And this is the thing with mainstream Scottish nationalists. They are not in a hurry: they think they have time on their side.

The recent polls explain why. The British state, surveys demonstrate, is facing a demographic time-bomb. Young people tend to support independence. And old people – the union.

🚨 NEW POST 🚨📈

— Scottish Election Study 🏴🗳️ (@ScotVoting) December 15, 2022

Support for Scottish independence has risen, but why?

What effect, if any, did the Supreme Court ruling have on levels of support? @frasmcm uses latest SCOOP data to take a look 👇https://t.co/DhPOmw3XG3 pic.twitter.com/yidnle07PO

It is hard to overstate how dramatic this generational division is. Let us look at the detail from a poll from shortly after the Supreme Court ruling. It was by Ipsos and it showed 56 per cent of Scots backing independence. That is a bit of a peak. Most polls put the Yes lead a little lower than that.

🏴 Support for Scottish independence by age, from the latest Ipsos Mori poll:

— Ross Colquhoun (@rosscolquhoun) December 7, 2022

16-24: 73%

25-34: 68%

35-44: 61%

45-54: 53%

55-64: 47%

65+: 45%

🗳 With hard work and public pressure we will deliver independence for Scotland.

But when voters were broken down by age, a real pattern emerged. Fully 73 per cent of Scottish residents aged between 16 – when we get the vote here – and 24 wanted a sovereign state. Only 45 per cent of those over 65 did.

In fact, there was majority support for independence all age groups under 55.

This pattern is repeated in all polls. It is almost the defining feature of Scottish politics: a huge generational gap in how people view the state.

The age gap in recent polls on Scottish independence is striking, with 72 per cent of 16-24 year olds saying they would vote to leave the UK, compared to 40 per cent of over-65s. Read Prof Sir John Curtice’s analysis for the BBC here: https://t.co/NAuelGiJFe

— James Cook (@BBCJamesCook) December 14, 2022

The gulf between youth and experience, I think, raises an obvious question. Will Scots get more unionist as they get older? Or will the youthful Yes cohort of independence supporters stay true to their cause as they age?

I can understand why some older people would be worried about Scottish sovereignty. Change can be scary. Diehard Yessers rarely admit it, but there is every chance of a period of uncertainty and difficulty after independence. This happened, for example, in the Republic of Ireland. Even with a fair wind, it can take time to build institutions and put the new state on an even keel. If you are over 65, that might be time you do not have.

📊Another Scottish independence poll, via @YouGov (+/- v October 2022):

— Mark McGeoghegan (@markmcgeoghegan) December 12, 2022

Yes - 47% (+4)

No - 42% (-3)

DK - 8% (+1)

Post UKSC decision average (+/- v October 2022 average):

Yes - 50% (+4.75)

No - 43% (-3.75)

DK - 5.8% (-0.7) pic.twitter.com/zKzpuoHG6J

Take pensions. Here in Scotland this is one of the most fraught issues. Seniors have been bombarded with confusing claims and counter-claims about their old age stipends. So, perhaps, voters pushing 65 and older will always be cautious about voting Yes.

Or perhaps not. There is another way to look at these numbers. That is that today’s old and very old were born or brought up at the height of cultural Britishness, during World War Two and its aftermath.

This generation experienced the birth of the welfare state and perceived “national” British institutions like the NHS and BBC television.

They feel Scottish but British too. And that matters in politics.

During the Indyref of 2014 I vividly remember going to an old-folk’s home in the solidly working-glass town of Clydebank to interview residents about what they thought of independence.

The entire community gathered in a big circle of chairs, tea and biscuits on their laps, and basically pledged their allegiance to Britain. They were passionately, viscerally unionist. There was one man – a retired merchant sailor well in to his 80s – who summed up the mood. “I was torpedoed as a Briton and I will die a Briton,” he told me. And, boy, did he mean it.

I mention this episode because Clydebank – like the rest of the industrial or post-industrial west of Scotland – is home to pretty strong pro-independence sentiment. And even those who voted No would often have done so out of pragmatism rather than the kind of loyalist passion the elderly seaman had for Britain. Those pensioners felt, well, out of era.

Back in 2014, Yes got 45 per cent across Scotland. Today the last four polls, according to people who monitor these things, put support for independence at an average of 54 per cent. That is up from an average of 51 per cent in the last three months of 2022.

Scottish Independence polling Q4 2022 Average (changes vs Q4 2021 Average):

— Ballot Box Scotland (@BallotBoxScot) December 24, 2022

Yes ~ 47.7% (+2.4)

No ~ 45.3% (-1.4)

Don't Know ~ 6.4% (-1.1)

Excluding Don't Knows (/ vs 2014):

Yes ~ 51.3% (+2.0 / +6.6)

No ~ 48.7% (-2.0 / -6.6) pic.twitter.com/IXNiS9zXXV

No doubt independence supporters will claim this is down to their ability to win arguments. Me? I think there are very few swing voters and undecideds.

So I am going to very carefully suggest at least another factor in the changing fortunes of Yes and No: there is a cohort effect. This is a delicate way of saying old unionists are dying and not being replaced.

Council areas by Independence vote based on Q4 2022 average, on uniform swing vs 2014 (vs Q4 2021 / vs 2014)

— Ballot Box Scotland (@BallotBoxScot) December 24, 2022

Yes ~ 17 (+5 / +13)

No ~ 15 (-5 / -13)

(Even more "just for fun" than Parliamentary projections! Projection caveats: https://t.co/f88QQRwMpz) pic.twitter.com/cpW9kWMDyd

Pro-UK politicians accuse any nationalist who raises this issue of being insensitive, morbid even. They have a point: nobody wants the grim reaper on their side.

This, of course, is not just a Scottish story. Boomers, to give the main No generation its name, have been a bulwark of Britishness, political and cultural.

Their gradual passing means unionist politicians will have to work extra hard to win over younger and even middle-aged Scots who have got used to the idea – the dream – of an independent state in the EU.

Nationalist leaders back in 2014 kept telling us all that the big vote could be “once in a generation”. This warning has been repackaged by their opponents as a promise. But – if the cohort effect is real – it is nationalists, not unionists, who have the most to gain by waiting for a generation to change.