ON Monday morning, at 9.30am on January 20th 1902, a large part of the Smithfield Flax Spinning and Weaving Mill, locally known as Pipe-Lane Mill, collapsed without warning, killing 14 women and girls and seriously injuring scores more, many permanently maimed or injured for life. The disaster was widely reported in newspapers across Ireland, Britain and elsewhere. The Irish News, described it as the “most deplorable disaster that has occurred in Belfast in the history of the city".

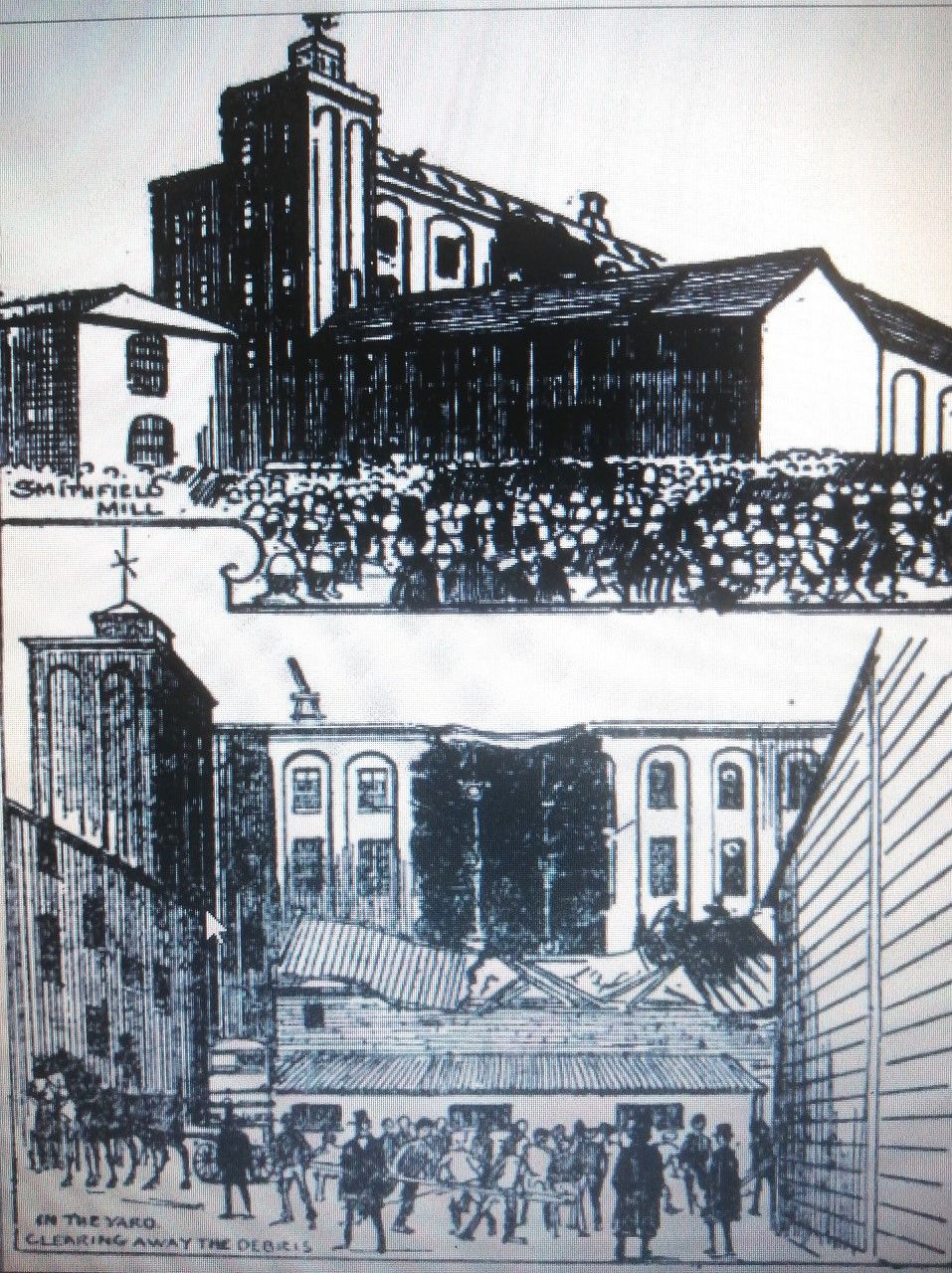

Hundreds of workers, mainly women and girls had just started their day’s work when the accident occurred. Eyewitness and survivor accounts showed that the collapse happened without warning, and with incredible speed. The five-story mill had a massive portion of its front wall ripped apart and entirely collapsed, leaving a huge gaping hole into the side of the entire structure. It was not understood at the time what exactly had caused the collapse but it was speculated that a support pier buckled and collapsed on the fourth floor which gave way, crashing down, carrying the lower floors and 30 tonnes of machinery with it. The devastation was such that tonnes of debris was piled twenty feet high and reached above the first floor.

The mill, erected in 1854, employed about 600 people and was known locally in Belfast as ‘Pipe Lane Mill’, the former name of Winetavern Street. The mill front faced onto Smithfield Market Square, the rear extended to Samuel Street towards North Street and adjacent to West Street and Winetavern Street. The Managing Director was Arthur T. Herdman, whose family held the main ownership interests in the company.

The extensive press reports of the scene made for heartrending reading as details emerged of the tragedy, with over fifty workers injured, and the high death toll of 14 lives lost, all females aged between 15 and 40-years-old. The Irish News provided a detailed account on 21st January. Fire crews, fleets of ambulances and police were quickly on the scene to attempt rescue and evacuation operations to Belfast Royal Hospital in Frederick Street. A survivor at the scene said “that she had not entertained the slightest fear of the safety of the wall, nor could she say how the accident occurred. At breakfast time she noticed nothing wrong, and the building appeared all right when the operatives returned to work at nine o clock. As awful panic ensued when the accident occurred, and those near at hand ran for their lives.”

Belfast Newsletter Sketches of Pipe Lane Mill, Smithfield, January 21st, 1902. Before and after the Accident

The emergency services at the scene struggled desperately to rescue and save as many lives as possible. Throughout the day masses of debris, machinery bricks, concrete and the falling masonry and metal remained highly dangerous and continued to hamper the rescue effort.

The huge gash in the collapsed wall was at least thirty feet across and continued down through each floor, the huge gaping hole completely visible to onlookers. Shovel, picks, wheelbarrows and hands, were all used in frantic efforts to carry and remove the fallen debris, where so many workers were buried underneath. A millworker clarified that 50 employees worked on the ground floor; 30 on the first, both flax preparation rooms;105 on the second floor; 115 on the third, both spinning rooms, and 80 based on the fourth floor, the reeling room.

The wall caving in smashed the supporting beams and the flooring unable to support the heavy machinery, crashed down through each of the rooms beneath, plunging all working in those locations with them. The Bideford Weekly Gazette on January 28th, quoted a survivors tragic account,

“A young girl named Burns states that she was working on the top floor, some 50 to 60 feet above the ground at the time of the accident. She darted to a place of safety on the broken flooring. But her sister who had been working alongside her, fell to the bottom, her lifeless body being recovered some hours later.”

The fire crews, police and medics assisting in the desperate rescue operation were commended afterwards for the energy and courage they brought to the task. The Irish News singled out in particular the heroic efforts of Father Small, the Catholic priest at the nearby St Mary’s Church and Constable Denis Murphy of Queen Street police station,

“….regardless of the threatening appearance of the broken building, the two hurried up the stairs to the upper stories, where several injured were seen crushed… With a heroism, which on the battlefield would win medals only for the brave of the brave, Father Small placed himself in every danger…Standing on the brink of a terrible chasm filled with steam sent forth in volumes from the broken pipes, drenched with water, and surrounded by the greatest danger, this heroic priest rescued where he could, and where not he administered the consolations of religion to the injured by his side with as much coolness and sympathy as if at a deathbed in the street below.”

Likewise, Father Magennis, also a curate as St Mary’s Church, supported as many as possible on the lower floors and, “…moved about with composure in the greatest danger of being consigned to the fate of those whom he was, with so much courage, working for, and administered the Holy Viaticum to the dying and badly injured. The presence of a priest afforded great consolation to the poor beings, and their heart broken relatives, nearby, did not fail to show their gratitude with tears and blessings.”

Map, Belfast Historical Towns Atlas No17; Smithfied,Belfast, 1900. showing location of Flax Spinning and Weaving Mill. Top Left.

As news of the accident spread in adjoining districts large numbers of the public crowded along Winetavern Street and West Street and lanes close to where the factory was located. The crowds included many anxious relatives who were frantic for news of family members and friends employed at the mill. The police cordoned the area off in front of the mill to support the search and rescue efforts. The Ballymena Weekly Telegraph’s report of January 25th stated, “The police were kindly but firm with distracted women, who pleaded to be allowed to search for missing relatives. One of them raised her hands to Heaven and implored on her knees that she might look for her “wee girl.” But it was useless to grant her request—the child lay, in all probability beneath the fallen and distorted masonry many tonnes in weight…”

“At half past ten it was still feared that some twenty women and girls were buried in the debris. The last two bodies removed were those of a dead girl and woman. The poor girl’s body was completely flattened from the head downwards, but her face was unharmed, and she wore a peaceful look, which showed that death had been mercifully sudden. The woman was also lifeless and her face covered with blood, and apparently scalded.”

The Newsletter’s reporter in their January 21st edition, said he had witnessed a moving moment which, “…showed in a marked degree how the bond of sorrow brought together women, who up to that time, had been total strangers to each other. A poorly-clad woman, who carried a little child in her arms, inquired from another whether she also had lost her “wee” child, and the reply being in the affirmative, they sobbed and cried together in sympathy.”

Tragically it also later emerged that a young girl unemployed for some time, was attending the mill to discuss starting a new job there when the accident occurred, and tragically died when the collapse occurred.

During the course of the rescue efforts fleets of ambulances removed the injured survivors and dead recovered from the wreckage to the Belfast Royal Hospital in Frederick Street where highly excitable crowds assembled near the entrance desperate for news of their relatives. The Irish News paper reporter stated, “many of the incidents were heartrending in the extreme, and moved even the most experienced officials of the institution. Brothers looked for sisters, parents for their children, and vice versa, and the arrival of each case was for some a further lease of fond hope and for others the final confirmation of struggling despair.”

Lizzie Campbell, died of her injuries at the end of January and brought the total fatalities to fourteen. Over fifty had been injured, and treated for serious head injuries, fractures, and severe lacerations; many were maimed and left permanently disabled for the rest of their lives. Messages of sympathy and condolence poured in from organisations and the public from Belfast and across Ireland, including from Belfast’s Lord Mayor Sir Daniel Dixon and the Lord Lieutenant in Dublin, Earl Cadogan.

Two relief funds for the survivors and bereaved families of the Mill Disaster were set up in Belfast – The Lord Mayor’s Relief Fund and the Belfast Evening Telegraph Relief Fund. The Belfast Weekly News of 28th May, 1908, reported that the Smithfield Mill Relief Fund launched in 1902 was formally wound up. A total of £3,085 had been raised and distributed to assist bereaved families, employees who had been made unemployed, injured workers and those suffering from prolonged illness. In addition, the Workmen’s Compensation Act of 1897 provided financial compensation in the case of dependent families of workers who had lost their lives, or survived but with series injuries or long term/permanent disabilities. On the 12th February the inquest verdict concluded,

“The collapse of the mill was due to the defect at the base of the piers and that the defect could not have been discovered by ordinary inspection, and that no blame can be attached to any person in connection with the accident.”

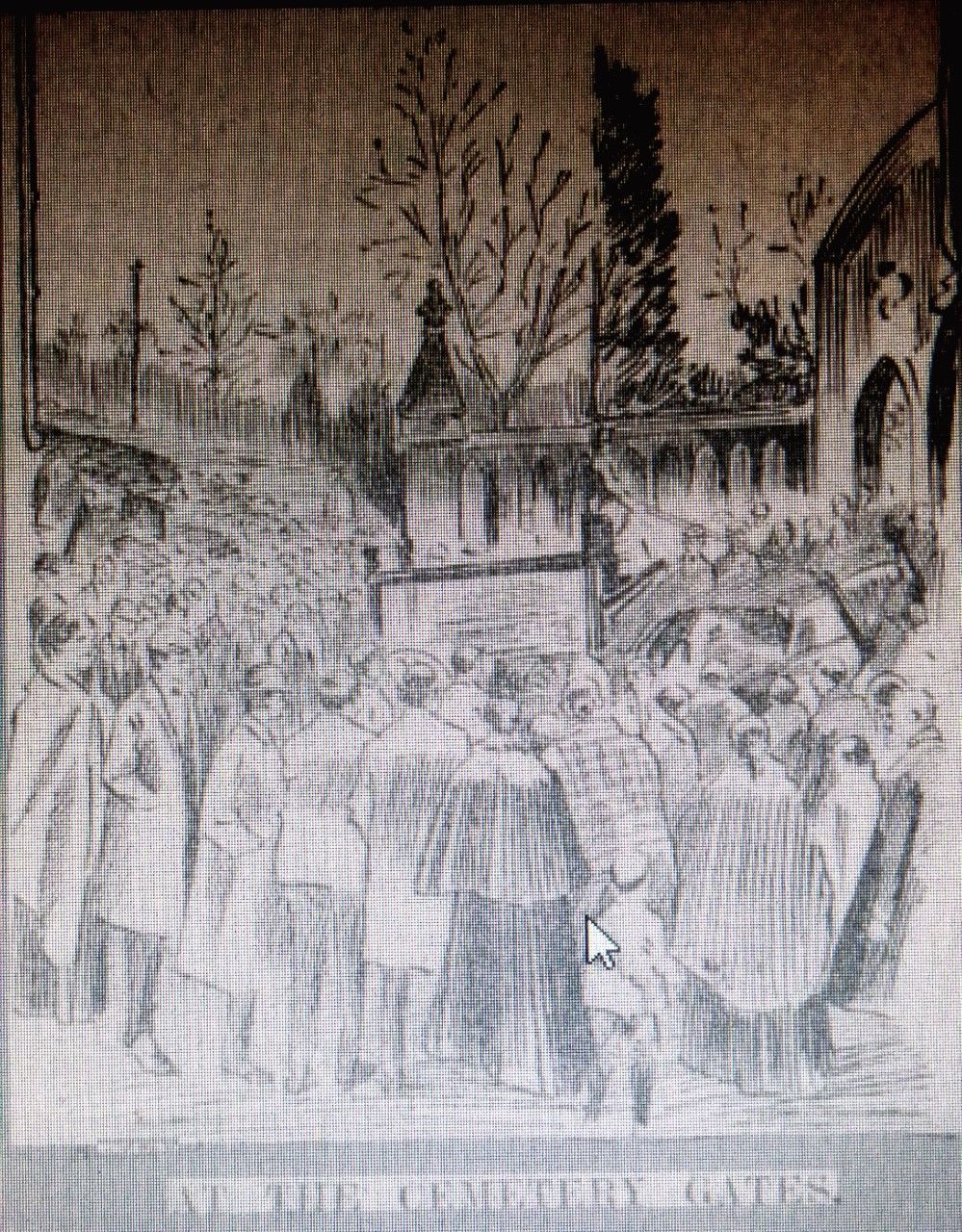

Belfast Evening Telegraph, January 23, 1902, Mourners at Funerals of Smithfield Pipe Lane Mill Disaster, Milltown Cemetery

In the aftermath of the disaster, on the January 22nd, eight funerals took place at Milltown and Belfast City Cemeteries at short intervals; the funeral cortege numbering many thousands of mourners at the cemeteries and lining their approaches along the Falls Road. Hundreds of women and girls employed in the various mills across the city attended. “Women covering their heads with shawls, and babies nestling in their arms, also followed the hearses the whole way, and gave piteous expression to their sorrow.” Mr A.T. Herdman, Managing Director and other senior management represented the Smithfield Flax Mill at the funerals. Further funerals took place in the days that followed, also attended by large numbers of mourners.

The Lord Mayor convened a Town Hall meeting on 23rd January, to launch a Relief Fund and offer his condolences for the victims' families. The Right Honourable Thomas Sinclair, tendered the meeting’s profound sorrow and deepest sympathy to the families of the bereaved, adding, “…the sufferers were all the children of toil. They were humble but none the less useful members of that great industry which was the staple enterprise of the city and province, and whose welfare has been for generations so closely linked with the prosperity of the North of Ireland”.

Despite the tributes, expressions of condolence and assurances of support, 14 women and girls were dead and many survivors left with life changing injuries. The Pipe Lane Mill disaster was another tragic episode in the history of the mill workers in Belfast. The historical narrative of life working in the mills “the great industry”, of largely female employees, was very different. James Connolly portraying the women as the ‘Linen Slaves of Belfast’, said in 1913, “…the conditions of your toil are unnecessarily hard, that your low wages do not enable you to procure sufficient nourishing food for yourselves or your children, and that as a result of your hard work…you are the easy victims of disease, and that your children never get a decent chance in life, but are handicapped in the race of life before they are born. All this is today admitted by every right-thinking man and woman... Belfast Mills are slaughterhouses for the women and penitentiaries for the children.”

Brendan Muldoon ©2022