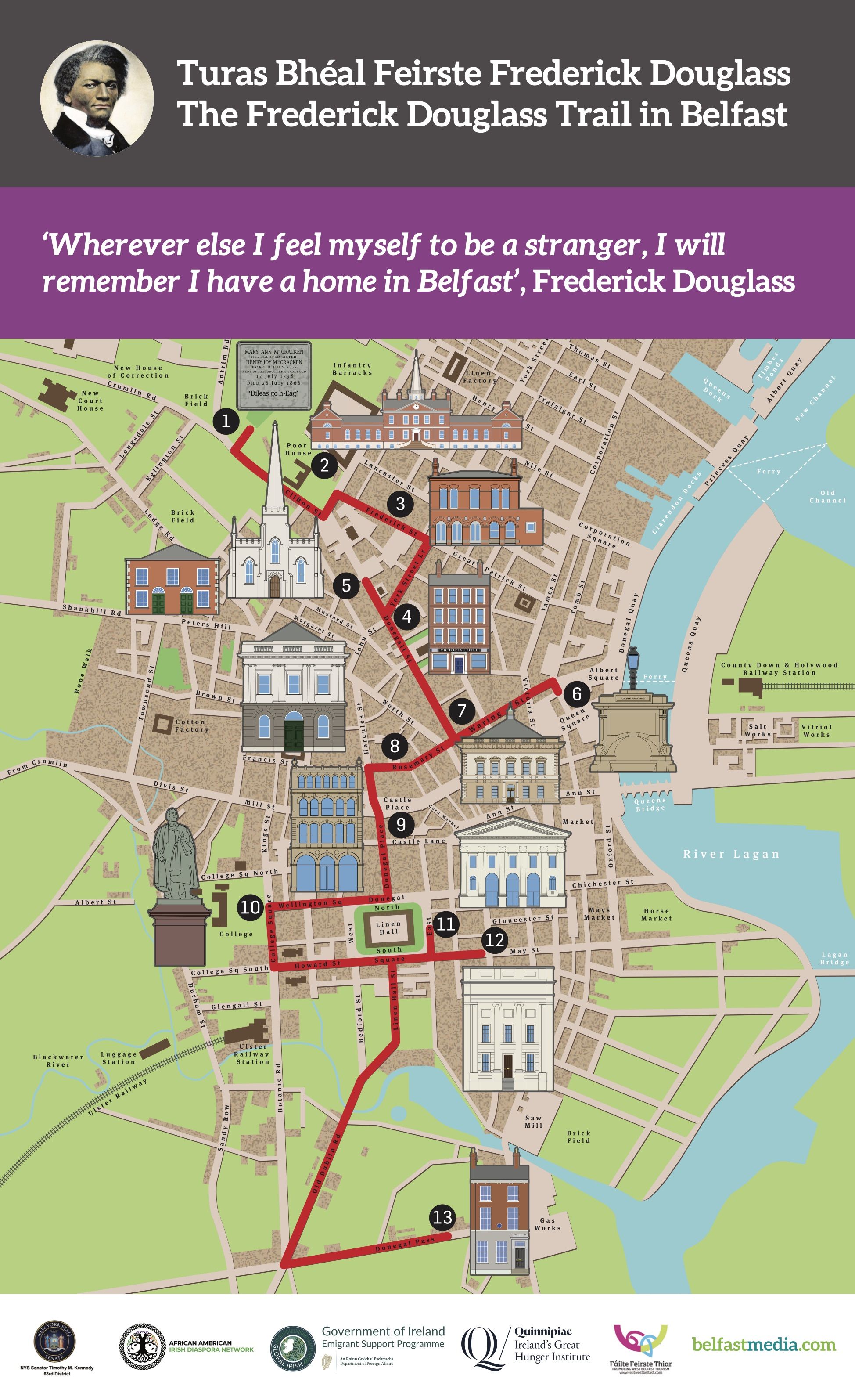

The Frederick Douglass Belfast Walking Trail will be launched at 11am today (Tuesday) as part of the Féile an Phobail celebrations. You can watch back on the launch below.

When Frederick Douglass arrived in Belfast in early December 1845, he had been in Ireland for three months and had achieved a level of comfort, acceptance and happiness that he had never experienced before. The 27-year-old ‘fugitive slave’ was there at the invitation of the Belfast Anti-Slavery Society.

At this time, Belfast was a town, only achieving city status in 1888. The year 1845 was significant for another reason. In late August, a deadly disease appeared on the potato crop, plunging Ireland into one of the most lethal famines in modern history. All parts of the country suffered, including Belfast, where potatoes were a staple food for the poor. As the famine progressed, people from the local countryside fled to the town looking for work, relief, or seeking to emigrate. Private bodies such as the Charitable Society struggled to assist them.

Before leaving Belfast in January 1846, Frederick uttered the heartfelt words, "Wherever else I feel myself to be a stranger, I will remember I have a home in Belfast." Frederick returned for three brief visits later in 1846.

This is a suggested route as the trail is drop in/drop out. It will introduce you to some of the sights, sounds and smells that Frederick experienced and the people and places he encountered. There have been some changes in the numbering of houses and buildings.

1. Grave of Mary Ann McCracken: Clifton Street Cemetery, (entrance) Henry Place

The Clifton Street Graveyard, or New Burying Ground, was opened in 1797 by the nearby Belfast Charitable Society. Mary Ann McCracken (1770-1866) was buried in Plot 35. She had been inspired by Frederick’s visit to revive a women’s branch of the anti-slavery society. Mary Ann’s grave remained unmarked for over 40 years. In 1902, the bones of her beloved brother Henry Joy, who had been executed in 1798, were placed nearby.

William John Brown from Maryland, who had escaped enslavement as a stowaway on a ship from New Orleans to Belfast, was buried here in 1831. His wife and children remained enslaved.

The graveyard, a registered historical site, can be accessed through prior agreement.

2. Clifton House, 2 North Queen Street

Clifton House

Clifton House, a beautiful example of Georgian architecture, was opened in 1774 as a poorhouse and hospital infirmary by the Belfast Charitable Society. The Society had been founded in 1752 to provide refuge for the poor and vulnerable. Robert and Henry Joy McCracken oversaw the construction of the house, while their niece, Mary Ann, helped establish a Ladies’ Committee in the 1820s. Tours of the House’s Interpretive Centre and the nearby cemetery can be arranged.

3. Lancasterian School Room, 42-45 Frederick Street

One of Frederick’s final public appearances before leaving Belfast was before children in the Lancastrian School Rooms. He spoke about abstinence from alcohol. The Lancasterian School Rooms were named after Joseph Lancaster, an English Quaker educator who believed that the best way to learn was by teaching—hence gifted students became teaching assistants. As industrialization spread, towns such as Belfast established these schoolrooms to provide education to the poor. The Frederick Street School opened in 1811 for 700 pupils.

The site of the school also housed the Meeting Rooms of the Society of Friends. Due to their growing numbers, in 1839 Quaker architect Thomas Jackson designed a larger building. Part of its frontage has survived.

4. Victoria Hotel, 1 York Street (corner of York and Donegall Streets)

One of the things that proved liberating to Frederick was the lack of racial segregation in public places, including hotels. In Belfast, Frederick stayed at the Victoria Temperance Hotel. Regardless of the success of the temperance movement, the life of this hotel was short. By 1850, it had become an outlet for selling ‘Teas, Coffees, Foreign Fruits, Wines and General Groceries’.

5. The Cathedral Quarter: Independent Meeting House, 77 Donegall Street, and Presbyterian Church, 60 Donegall Street

An Independent Church of ‘spartan simplicity’ was constructed in Donegall Street in 1804. It was referred to as the Evangelical or the Independent Meeting House and was part of the Congregation Union. The original building was demolished in 1858 to make way for a larger venue, which opened in 1860 and was known as the Congregational Church.

Frederick’s first lecture in Belfast took place on 5 December 1845 in the original Independent Church. It was chaired by the town’s Mayor—an honour not possible in America. Frederick lectured here again on 23 December and during his final Belfast lecture in October 1846. It is now Redeemer Central.

Donegall Street was home to several other churches. The Donegall Street Presbyterian Church opened in 1792. In 1842, Rev. Isaac Nelson (1802-1888) was installed here and for almost four decades preached his own brand of evangelical Presbyterianism. Nelson was an ardent abolitionist and described Frederick as a ‘literary wonder’ and ‘intellectual phenomenon’. Nelson’s independent spirit was apparent in 1880 when he exchanged his religious vocation for a political career, becoming nationalist MP for Co. Mayo. Following Nelson’s controversial departure, the church fell into disrepair and was demolished.

While Nelson’s remarkable legacy was erased from Donegall Street, in 1887, the Nelson Memorial Church was opened in the Shankill Road. It no longer functions as a place of worship.

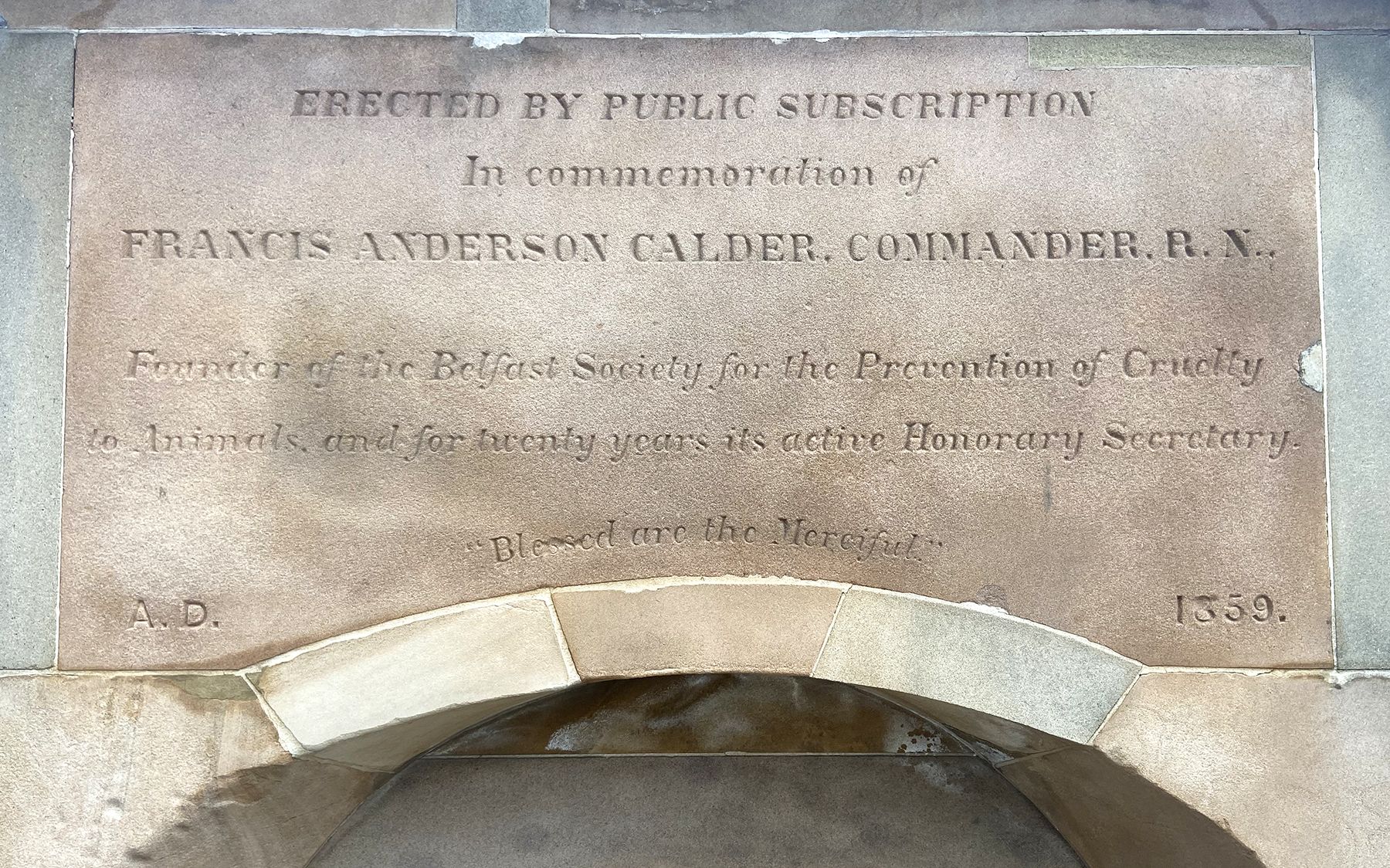

6. Calder Fountain, Custom House Square

CALDER FOUNTAIN

In Belfast, Frederick was hosted by Francis Calder, one of the Secretaries of the Belfast Anti-Slavery Society. Born in Edinburgh, Calder, who had served in the Royal Navy, was deeply religious and known for his philanthropic activities, including abolition and animal welfare.

In 1836, Calder founded a society for the protection of animals—probably the first in the world. He was particularly concerned that horses and cattle did not have access to water so he installed troughs at strategic locations. The beautiful Calder Fountain paid tribute to his work. The fountain is on the south side of the elegant Custom House Square. The Custom House, designed by Charles Lanyon, was opened in 1857.

CALDER FOUNTAIN

7. Commercial Buildings and Assembly Room, 1 Waring Street (adjoining Bridge Street) FREDERICK'S FAREWELL TO BELFAST: The Assembly Rooms.

The Commercial (Exchange) Buildings on Waring Street are another example of Belfast’s Georgian architecture. Built in 1769 as a single-storey arcaded trade house, in 1820, a second storey was added. By the late 1840s, the buildings housed a hotel, a bank and a newspaper office.

In the early 1920s, part of the site was taken over by the Northern Whig newspaper.

In January 1846, the Commercial Buildings hosted a farewell breakfast for Frederick. He was presented with a pocket bible by the Belfast Anti-Slavery Society. The formation of a Belfast Female Anti-Slavery Society was also announced.

8. First Presbyterian Church, 27 Rosemary Street

Belfast’s First Presbyterian congregation dates back to 1642. The opening of the First Presbyterian Church in 1672 on Rosemary Lane (later, Street), indicated the growth of Presbyterianism within the town. By 1707, the church was too small for its congregation so a second larger meeting place was built, adjoining the original one. A third Presbyterian church was built on this street in 1722.

By the late eighteenth century, these three churches were associated with the radical ideas of a generation of remarkable republican nationalists, including Henry Joy and Mary Ann McCracken, William Drennan and Rev. Kelburn Sinclair. They inspired the founding of the Society of United Irishmen in 1791, whose progressive ideals included ending slavery. Another founder, Samuel Neilson, hosted Equiano Olaudah during his visit to Belfast in 1791. By the 1840s, all three churches on Rosemary Street supported abolition.

FUGITIVE-SLAVE: Frederick Douglass

Of the three Presbyterian churches on this street only one remains. The Second Presbyterian congregation moved, in 1896, to Elmwood Avenue and created All Souls’ Church. The Third Presbyterian Church was destroyed in 1941, during the Blitz. A decade later, the Masonic Hall was built on its site. The First Presbyterian congregation on Rosemary Street, now known as the First Church, is Belfast’s oldest surviving place of worship. The current building opened in June 1783 and is a fine example of Belfast’s Georgian heritage. In 2020, a proposal to erect a statue to Frederick Douglass on the church grounds achieved all-party agreement.

9. Primitive Wesleyan Church, 6-10 Donegall Place

Regardless of its central location and prestigious designer, Charles Lanyon, the history of this church was brief: opening in 1840 and closing in 1885. The church buildings included a schoolhouse for over 500 children. The church’s closing was prompted by realignments within Methodism. Frederick gave an anti-slavery lecture here in December 1845. In July 1846, he lectured here on two occasions. GREEN MAN

The Lanyon firm also designed the nearby Linen Hall Library, on route to the Black Man Statue. The building initially opened as a linen warehouse in 1864, becoming home to the library after 1891. The library’s origins date to 1788.

10. Statue of the ‘Black Man’ /Royal Belfast Academical Institution

Although referred to as ‘the Black Man’, this copper monument to Rev. Henry Cooke is a patchy murky green due to oxidization. Inaugurated in 1876, the statue was not here during Frederick’s visit to Belfast, but the Rev. Cooke was. Cooke, an evangelical Presbyterian minister, was openly anti-Catholic and anti-nationalist. But he did support abolition. To conservative Protestants, Cooke was a hero who deserved to be memorialized. The statue’s back faces the nearby Royal Belfast Academical Institution (opened in 1814) because Cooke opposed the religious tolerance the Institution promoted. Meetings of the Belfast Anti-Slavery Society were sometimes held in the Institution.

11. Methodist Church, Donegall Square, East

Frederick gave his second Belfast lecture in this church in December 1845. Shortly after, the so-called ‘old Chapel’ was demolished to make way for an elegant new chapel, which could accommodate double the congregation. It opened in 1847.

At the time of Frederick’s visit, Donegall Square housed the White Linen Hall, the centre of Ulster’s profitable linen industry. When Belfast gained city status in 1888, it was decided a city hall should be built on this site. The City Hall was completed in 1906. In 2021, it was agreed that a statute to Mary Ann McCracken should be placed in the grounds of the City Hall.

12. Music Hall, 2-12 May Street

The Music Hall was opened in 1840 by the town’s Anacreontic Society (named after the ancient Greek poet Anacreon, who loved poetry and wine), designed by Quaker architect Thomas Jackson. The Music Hall could seat around 800 people on two public levels. Around 1886, it was purchased by the Church of Ireland Young Men’s Society and later renamed the Victoria Memorial Hall.

In October 1846, Frederick lectured here with William Lloyd Garrison, his mentor and the founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Garrison’s confrontational style did not find favour with the Belfast audience. The nearby Presbyterian Meeting House was then associated with Rev. Henry Cooke—the ‘Black Man’. The church had been built for him in 1829 and reflected the town’s move towards a more conservative version of Protestantism.

The Music Hall was demolished in 1983, despite being recognized as a place of ‘special architectural and historical interest’. A sign saying ‘Music Hall Lane’ survives near the site of the original building.

13. Home of Mary Ann McCracken, 62 Donegall Pass

The name Donegall Pass pays tribute to the Donegall family, who were the owners and landlords of the town until the 1850s. As the town grew, Donegall Pass, to the south-east of the town centre, was developed. Mary Ann McCracken spent her later years living here. Even in her 80s, she remained an ardent anti-slavery activist.

In 1999, the Ulster History Circle erected a plaque to honour Mary Ann, describing her as a ‘Social Reformer’.

After Belfast

Frederick left Belfast—and Ireland—in January 1846. He described his time in the country as the "happiest moments" of his life. From Belfast, Frederick sailed to Scotland, where he increasingly felt isolated and homesick. He returned to America in April 1847.

Belfast was one of the first places in Ireland to commemorate Frederick Douglass’s historic visit. Although not part of the Trail, the Frederick Douglass mural, located on the ‘Peace Wall’ near the Falls Road, is worth visiting. The mural honours not only Frederick, but many champions of human rights, including Daniel O’Connell, Rosa Parks, Nelson Mandela and, since 2014, Congressman John Lewis.

The Frederick Douglass Trail in Belfast is part of the Frederick Douglass Way in Ireland. It has been created by Christine Kinealy, supported by partners on both sides of the Atlantic. Publication of the Belfast map has been sponsored by the Belfast Media Group. The map will be launched at Féile an Phobail in West Belfast on 10 August at 11am.

© copyright Christine Kinealy

www.blackabolitionistsinireland.com

Map Design: Ron Wilson