THE Ark wasn't a big public house. Situated at the corner of Broadbent Street on the Old Lodge Road it consisted of a public bar, partitioned from a more discreet backroom and a snug. That was it. A backdrop of shelved whiskey bottles fronted by a no-nonsense wooden counter which separated myself and the only other barman from the clientele. Porter was the staple and non-sectarian drink. Firkins of it were delivered weekly from Guinness’s yard on the Grosvenor Road, manhandled into place behind the counter and dispensed with much care into pint glasses. I will tell you about that some other time. Pints of porter. No Double X or draught beers. Wee Willie Darks, bottles of Red Heart, Carling Black Label and Tennent’s were minority brews.

A wee Mundie’s or the cheaper Drawbridge wine was a more popular tipple. A bottle and a half ’un were strictly Friday or Saturday night treats. Sales of spirits were minimal. An occasional gin for the women to augment their more economical small sherries or port. No vodkas. No liqueurs. And no Pope. The customers were mostly Protestant, mainly male and totally working class.

They all lived beside the Ark or in neighbouring streets. These streets lay between the Old Lodge Road and the Shankill on one side and the Crumlin Road on the other side. It was a loyalist area. Working class to its core but with little collective consciousness of this or of their reduced place in society. Belfast’s shipyard was the main source of employment. Many of the Ark's male customers worked there.

St Patrick's Night in the Ark provided more entertainment . ‘When Irish Eyes are Smiling’ and ‘The Green Glens of Antrim’ vied with ‘The Boys of the County Armagh’ and ‘Danny Boy’. On one occasion I was moved to render a verse of The Sash – in Irish. A Somme Veteran followed me with a rendition of Kevin Barry. At the end of the night everyone stood for a collective voicing of God Save the Queen. I absented myself from that by clearing away glasses and empty bottles from the back room. Nobody minded.

The Twelfth was a public holiday. Not for bartenders, of course. But for almost everyone else. Most of the Ark's clientele didn't go to the Field. Many of the men weren't in the Orange Order. None of the women were. They weren't allowed. We all watched the big parade and they crowded around the bonfires on the Eleventh Night. They enjoyed themselves. It was 1965. They felt under no threat. That would come in its own time. They and we have only their leaders to thank for that.

I left the Ark following a wage dispute. I had asked for the union rate for working a public holiday – the Twelfth. Instead, I got the sack. I was sorry to leave my friends in the Ark. And they, diminished in numbers by the ongoing levelling of their homes, were sorry to see me go.

I journeyed daily along the Falls, across the Shankill and up the Old Lodge. Frequently I collected tripe, to be boiled with onions for a dart match buffet, from a Shankill Road butcher. Occasionally I took the waters in Peter's Hill Public Baths. On warm summer nights I walked to Ballymurphy along the Shankill and the West Circular Road, stopping for a fish supper in the Eagle Supper Saloon on the way. Nobody bothered me. Maybe I didn't look like a Catholic. Or maybe nobody cared. Polarisation was peaceful. My only aggravation had occurred much earlier as a short-lived schoolboy boxing career came to an end in a Shankill Road Club when a Malvern Street sparring partner took me and his pugilistic skills more seriously than I did. That was in 1958. I was ten. When I worked in the Ark I was already involved in republican politics.

When the planners started the destruction of the Falls with the demolition of the Loney area and the building of the Divis Flats slum I and other republicans joined local people in protest. When the same vandalism started in the Old Lodge Road, I stood with locals at the door of the Ark and watched as the bulldozers destroyed and displaced a community. No-one protested. Everyone was sad. Some of the women showed a little anger. But none of the local men listened to them. They were only women after all. And no-one listened to me. I was only a wee Catholic barman after all.

But outside the Old Lodge Road and other neighbourhoods like it the snail pace of progressive politics was slowly taking on a new focus. In May 1965 a hesitant exchange of ideas between republicans, communists and unaffiliated trade unionists led to a conference on civil liberties hosted by the Belfast Trades Council. News of this did not trickle down to the folks of the Old Lodge Road.

I left the Ark following a wage dispute. I had asked for the union rate for working a public holiday – the Twelfth. Instead, I got the sack. I was sorry to leave my friends in the Ark. And they, diminished in numbers by the ongoing levelling of their homes, were sorry to see me go. They lifted a collection. Probably more than the day’s wage I was denied. I walked home up the Shankill as usual. Bonfires – manageably small ones – at most street corners. Lambeg drums being battered in some places. Hardly a Mardi Gras or a Féile an Phobail. But a festival of sorts nonetheless.

Although I never thought of it then, I probably got sacked at a good time. Peaceful polarisation was fraying at the edges. Ian Paisley was about to initiate a new quarter-of-a-century of long hot summers by leading a highly provocative and sectarian march into the nationalist Market area of Belfast. Soon there were serious incidents, including the murders of two Catholics and a seventy-year-old Protestant woman. Unionist boss Terence O'Neill met Dublin Premier Sean Lemass. A section of unionism was being reluctantly dragged into the twentieth century on the eve of the new EEC era.

They resisted this. Everyone paid the price for their stupidity. By now I was working in the Duke of York but spending all my free time on a Gestetener duplicating machine churning out leaflets on civil rights and other demands and learning the basics of political activism. The innocence of my days at the Ark were over. But I retain my affection to this day for the place and in particular for the fine loyalist people who befriended me there.

• DAVID TRIMBLE’S RISKS FOR PEACE

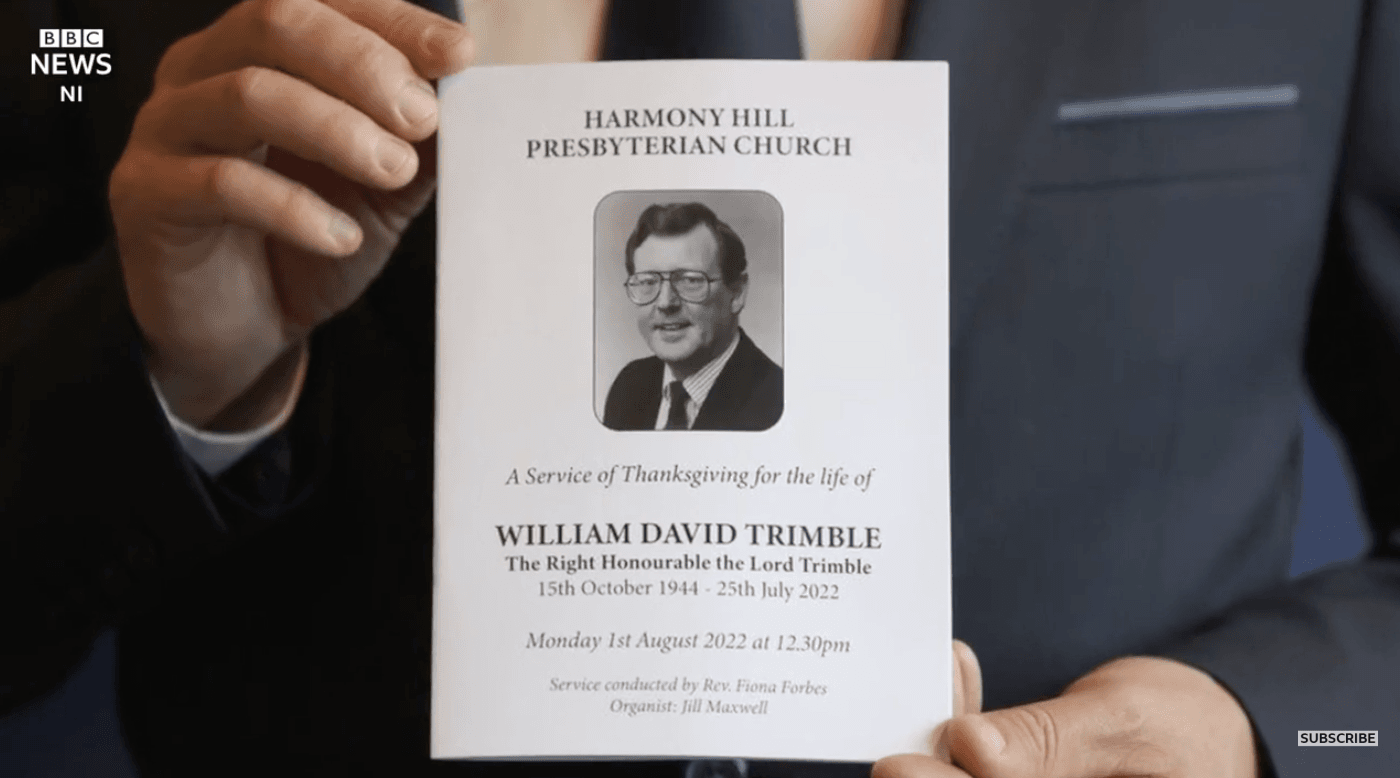

DAVID Trimble became First Minister, with Seamus Mallon as deputy First Minister, shortly after the referendum that endorsed the Good Friday Agreement. It was December 1999 before other Ministers were appointed. Among them were Martin McGuinness and Bairbre de Brún as Sinn Fein’s first two Ministers to the power-sharing Executive.

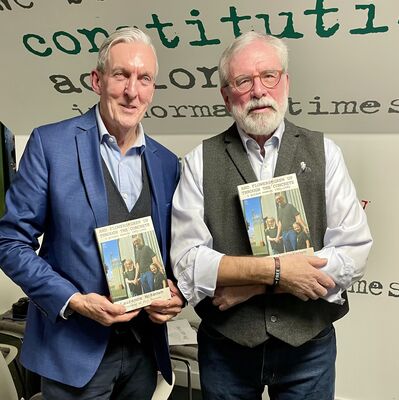

On Monday, Bairbre and I joined Michelle O’Neill, First Minister designate, and Alex Maskey, Ceann Chomhairle of the Assembly, and many others at the funeral of David Trimble. It was an occasion for reflection on the career of a unionist political leader who led his party into all-party negotiations and subsequently to signing up for the Good Friday Agreement.

It was also an opportunity to extend personally my sincere sympathies to his wife Daphne and to his children, their daughters Victoria and Sarah, and their sons Richard and Nicholas.

David faced huge challenges when he led the Ulster Unionist Party into Castle Buildings for the Good Friday Agreement negotiations. Unionism had dominated the north for generations and especially since partition. For almost 30 years there had been intense conflict. Taking risks for peace was always going to be hard for all sides. But despite these difficulties and the refusal of the UUP to talk directly to Sinn Féin during the talk process, we collectively succeeded in reaching an agreement.

In the years following the Agreement I met David many times. Our conversations were not always easy but we made progress. David’s contribution to the Agreement and to the quarter-century of relative peace that have followed cannot be under-estimated. I thank him for that.

Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam dílis.