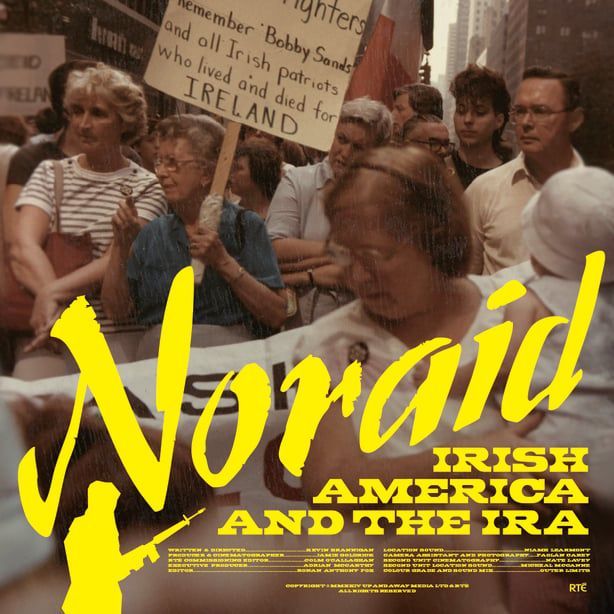

THE RTÉ documentary 'Noraid: Irish America and the IRA' was something that needed to be made. Despite its sensationalist title it is a sensitive two-parter that breaks with tired formats and relies entirely on archive materials, with primary interviews. Examining our recent past, in particular the political figures engaged in it, has become almost formulaic for film makers, and while hours of exceptional investigative journalism has been produced, even more hours of boring, repetitive and grating broadcasting has been made. This programme inserts itself as unique, fresh and thought-provoking.

It really is a tale of two halves, with the first episode examining Irish Northern Aid, its history, key figures, development and its critical relationship to Sinn Féin. It begins by raising money for political prisoners’ families, and becomes central to the development of the peace process and the Good Friday Agreement.

From the outset the figure of Martin Galvin is presented as, and proves to be, central. Anyone on either side of the Atlantic who knows Mr Galvin knows a force of nature. A man for whom time difference is irrelevant, his energy and commitment today is second to none. He gets up earlier than everyone else, works harder than everyone else and, if he goes to bed at all, it feels like minutes before he is sending emails and voice messages again. In the 1980s he became the face of Irish Northern Aid, its driver, and its beating heart. This documentary explores, in part, his motivation and his analysis of why this organisation became so central to the republican movement, and to Irish America.

At the heart of that development was the impact of the 1981 hunger strikes. The deaths of these ten young men on hunger strike are often cited as a seminal moment for politics on this island; this programme explores the impact on Irish America, and it was nothing short of seismic. Michael Shanley’s “beyond feverish” testimony of emerging from the New York Underground with his mother on to Third Avenue the day after Bobby Sands died speaks to his innate story telling ability as hairs rise on the backs of necks. An unsung raconteur, Mr Shanley also gives first-hand accounts of the New York protests in the months and years afterwards. His telling of his encounter with Sarah Ferguson on her way to see The Phantom of the Opera is worth the hour’s viewing alone.

The second episode focuses on the supply of arms from the United States to the IRA. In this part, Ardoyne man Gabe McGahey and Chicago-reared John Crawley explain in detail how weapons were procured and supplied to the IRA, and how this was a distinct and unrelated activity to the activities of Irish Northern Aid. Beginning with the words of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and RUC Chief Constable John Herman, the constant and repeated official narrative that 'Noraid' was using fundraised money to buy weapons for the IRA was tested and dismantled when Gabe McGahey said: "We didn’t need Noraid."

The second episode also examines the emergence of the peace process and the critical role of Irish Northern Aid in securing the visa for Gerry Adams MP to visit the United States in 1994. In one of the many gobsmacking moments of the documentary, Martin Galvin is seen asking then democratic primary candidate Bill Clinton from Arkansas if he would give Gerry Adams a visa to come to the United States and Governor Clinton made that commitment. This was a pivotal moment that secured endorsement from many Irish Americans hitherto cool about the peace process and republicans’ centrality to it, notably Senator Ted Kennedy.

The question of agents and informers is touched on across the episodes. From CIA agents planted into gunrunning stings, to the role of MI5 agent Denis Donaldson as a Sinn Féin representative sent to the United States. But this deserves to be a third episode that should be made some day.

The killing of John Downes at a 1984 internment rally at Connolly House frames the first episode. Clearly a politically motivated attack, designed to diminish active engagement by Irish America in the censored conflict, this killing is examined through the eyes of Martin Galvin, who described it then and now as “British state terrorism”. His final analysis is that far from diminishing the interest in the Irish conflict, it only served to heighten it.

That Martin Galvin has dedicated these latter years to securing a human rights-compliant justice process for victims and survivors from all backgrounds speaks to the impact of John Downes’ and others’ killings on him personally.

But it is the anecdotes of divilment that make this documentary stand out. From John McDonagh telling the tale of getting a huge billboard in Times Square to wish political prisoners a happy Christmas; through to the Mayor of New York telling a grumpy Prince Charles, “England get out of Ireland”; to Danny Morrison’s Playboy interview; this piece of political documentary and storytelling romps along.

The valuable analytical inputs of Morrison and Bernadette McAliskey are thought-provoking on many levels. When Morrison speaks about the importance of breaking censorship in the 1980s he states that “Irish Americans were more principled than successive Irish governments”, and this is the central question at the heart of the entire production. Irish Northern Aid supporters were, and are, described as “plastic Paddys”, “misguided” and not fully understanding our conflict or politics, and viewing Ireland through green-tinted glasses. This documentary confronts that narrative and exposes the actors involved as nuanced, informed and always connected to the contemporary conditions that prevailed.

Bringing busloads of Americans who had raised funds for political prisoners’ families to see the poverty, militarisation and conditions for nationalists and republicans in the North was groundbreaking – and myth-breaking. Boston’s Kathleen Savage came on the first trip. “I wanted to understand, so I went," she says. Kathleen has never stopped coming back and is as well known in the Rock Bar as she is in any bar in Boston.

A scene in which Sinn Féin’s Tom Hartley tells a delegation to be aware that they might be arrested, and, if they were to ask for solicitor Pat Finucane, would be heartbreaking if it wasn’t for him quickly quipping, "Now I will tell you about what to do if you are tortured." The unsure-if-he's-serious reaction of the delegation is priceless.

There are also potentially discomforting scenes with masked IRA volunteers at social events and on those buses, about which Michael Shanley says, “The IRA were part of the landscape then."

And that is the strength of the two hours. Nothing is constructed or false. Nothing is hidden, and there is no predetermined narrative. This is a previously unexplored part of the conflict and peace process story, with a goldmine of recordings and larger-than-life characters. And the significance of some of those glanced at could escape many. At the beginning Michael Maye, head of the Irish American Labor Coalition and head of the Uniformed Firefighters, one of the top labor union leaders who attended Irish Northern Aid events, is heard doing a recitation. Also seen are Congressmen Mario Biaggi and Ben Gilman, who headed the Ad Hoc Committee on Irish Affairs.

In passing, someone sings during a hunger strike event. This is John Sands, Bobby's brother, who along with Elizabeth O'Hara, Malachy McCreesh and Maura McDonnell, were on the platform with Martin Galvin in the demonstration against Prince Charles in New York. There is a tall man speaking at a rally about a new proposal for a Special Envoy for Northern Ireland – that is New York Assemblyman John Dearie, proposing the idea of a US Special Envoy and starting a ten-year campaign that would lead Bill Clinton to appoint George Mitchell, the facilitator of the Good Friday Agreement.

This two-hour piece refuses to drag you into every detail, but even seasoned political analysts will find much that is new, and much to be entertained and challenged by.

The ending leaves conversations to be had. But it is Michael Shanley who attempts to reconcile it all. Following the Good Friday Agreement, the political prisoners were released, and so Irish Northern Aid’s raison d’etre of raising money for their families came to an end. But the characters in the piece have not gone away. They have been engaged, and remain engaged in the promotion of the Good Friday Agreement and holding the British government to account, and are critical voices in the call for a referendum for constitutional change in Ireland.

And there is nothing plastic about that, then or now.

Noraid: Irish America and The IRA, Wednesday, July 9, 9.35pm. RTÉ One/RTÉ Player.