‘Inevitable’ is a pretty strong word and enough to make your average academic suck their teeth in despair. Nothing is inevitable they always say, and to state otherwise is bombastic and simplistic.

I respectfully disagree.

The constancy of those who wish to see Ireland unified, the growing weight of evidence that it provides a better future for all the people of this island, the utter redundancy of the status quo in the North, and the guarantee of a pathway to delivering it peacefully through the Good Friday Agreement, means the inevitability of Irish unity is very real.

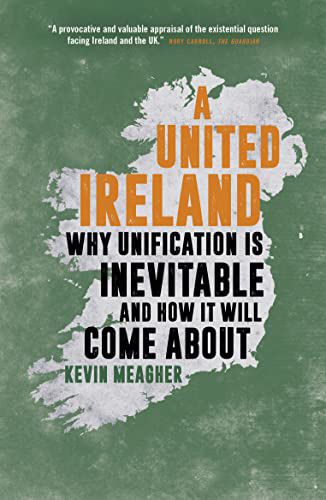

I’ve been thinking about all this as I updated my book on the subject: ‘A United Ireland: Why Unification is Inevitable and How it Will Come About.’ Much has changed since I wrote the first edition back in 2016, but I think the thrust of my argument remains valid, if not strengthened by how events have subsequently panned out.

The unquenched desire for Scottish independence, growing demands for devolution and ‘levelling-up’ investment across northern England, the manifest strength and dynamism of the southern Irish economy – combined with liberal changes to society there – are each powerful drivers for Irish unity.

Add in recent electoral results in the North, as well as changing demographics and it’s a heady mix.

The North is changing, southern Ireland is changing, and Britain is changing. What seemed if not impossible then unlikely a decade or so ago now feels very real.

Of course, wrapped around all this is a British ambivalence about Northern Ireland’s very place in the UK.

'No-one's interested in a united Ireland' (I paraphrase)

— Kevin Meagher (@KevinPMeagher) April 7, 2022

No sirree.

So I'll write a column talking about...a united Ireland.

Thus helping normalise the concept of...a united Ireland. https://t.co/PWo6lRhcwT

In March 2020, the pollster YouGov found that 54% of British people said it would not bother them ‘either way’ if Northern Ireland left the UK. A sentiment backed by 53% of Conservative voters.

This lack of interest will make it easier for British ministers to ‘lose’ the North at some stage down the road. Rather than a backlash from the public, there will be an audible sigh of relief.

What has quite obviously changed over these past few years is Brexit. Back in 2016, it was difficult to assess its full implications. Like most Westminster watchers, I thought the result of the referendum would be close, but that at the last minute enough voters would recoil from a leap into the unknown and Remain would squeak home.

Five years on, it’s clear that the DUP – lusty enthusiasts for quitting the EU – have made a much bigger miscalculation. They backed Brexit, unquestioningly, because they simply thought anything that made the North less European made it less Irish too. Their reflexive, narrow-minded tribalism has delivered the exact opposite of what they expected.

Instead of watchtowers and miles of razor-wire unfurled across the border, they are lumbered with the Protocol. Brought to them by a Conservative Prime Minister who told them to their faces at the DUP’s 2018 conference that he would never agree to a border-in-the-Irish-Sea.

And it’s not over yet.

The various free trade deals the government is negotiating – one of the main claims for Brexit – will do real damage to farming here once agreements with Australia and New Zealand are struck. A point made forcefully – and accurately – from no less a figure that agriculture minister Edwin Poots in one of those proverbial ‘stopped clock’ moments.

If you ignore the problematic questions on Irish unity and simply tot-up the parties with clear positions on the 'constitutional question' you get:

— Kevin Meagher (@KevinPMeagher) April 7, 2022

SF=+SDLP+PBP+Aon = 39.5

DUP+UUP+TUV+NI Cons = 40.2

Seems a more accurate reflection of the state of play.https://t.co/uWi0K2A0I4

Then there is what happens with the EU money tap is turned off for good.

€600m a year is a lot to lose for a place with just 1.8 million people. While the protocol is seeing trading patterns realign, with a huge increase in all-island trade to compensate for the decrease across the Irish Sea.

Commerce does not get emotional about borders. Nor is it particularly bothered about politics.

Despite the predictions and recent polling evidence, it will still be difficult for Unionists to internalise the prospect of Sinn Féin topping the poll at next month’s assembly elections, with the census likely to report that the contrived Unionist dominance of this place is now a thing of the past.

‘How has it come to this,’ they will no doubt ask? Probably triggering a bout of recrimination between the various political factions.

In chess, they call it ‘zugzwang.’ It is not quite checkmate, but it’s the point where the game starts to become irretrievable. Every move, (and, for here read every issue), weakens the overall position. There is no prospect of rallying to recover it.

So, yes, ‘inevitable’ is a word that leaves little room for chance.

Perhaps though there are times when you don’t need it.

Kevin Meagher is the author of ‘A United Ireland: Why Unification is Inevitable and How it Will Come About,’ (the second edition of which has just been published by Biteback)