AT the turn of the century in 1901 Belfast’s population was approximately 349,000, increasing to almost 387,000 by 1911. A third of its workforce was employed in manufacturing, dominated by three industries -– linen, shipbuilding and engineering.

Engineering and shipbuilding employed largely skilled, unionised and well-paid male workforces. Linen was largely unskilled and semi-skilled, paid low wages, and provided large supplies of ‘cheap labour', with a 70% per cent female workforce and large numbers of child labour. By 1900 there were over 60,000 linen workers employed in north-east Ulster with 900,000 spindles running in Belfast alone – more than any country in the world – and yet the grotesque conditions of work in the ‘dark satanic mills’ were notorious.

The city had one of the highest annual death rates within Ireland. In 1904 it rated as high as 77th out of 82 large towns in the UK for its death rate. The Irish News report of 1906, ‘The War Against Consumption’, revealed that of 79,500 deaths in Ireland in 1904, nearly 13,000 died of tuberculosis. The British Medical Journal (1896) ‘Sanitation and Housing in Belfast’, described conditions in the working-class districts of Belfast as “grave and deplorable”, condemning over 22,000 unsanitary back-to-back houses, and the practice of ‘jerry building’ of cheap flimsy substandard homes, often built on so-called ‘made ground’, reclaimed from ‘contaminated’ landfill sites.

These years became highly significant in Irish labour history, shaped by increasing social and class consciousness, and the growing momentum of women’s engagement in class struggle. There was considerable industrial unrest and confrontation between workers and employers not least within the linen industry with the 1906 and 1911 strikes and the famous Dockers and Carters strike of 1907. However, trade unionism in the linen industry was weak and catered mainly for sectional interests of ‘skilled’ operatives. By 1910 less than 12 per cent of the Irish linen workforce was organised.

With these challenges labours’ strength lay with the emergence of enlightened and charismatic leaders, including Mary Galway from West Belfast, appointed organising secretary for the Irish Textile Operative’s Union in 1897, the first woman to hold such a position in the Irish trade union movement. She was an active member of the Belfast Trades Council and elected Vice President of the Irish Trade Union Congress in 1910. James Connolly had settled in Belfast in 1911 as Belfast Secretary and Ulster District organizer of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. James Larkin was a leading trade union organiser, and led the famous Belfast Dock Workers' strike of 1907 and founded the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union in 1909. Joe Devlin MP, represented West Belfast for the nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party and was a formidable politician in the House of Commons as an advocate of social, public health and labour reforms.

Sculpture of Belfast millworker 'Millie' in Cambrai Street on the Crumlin Road

A momentous and far-reaching development occurred with the highly publicized report in August 1910, by Dr H.W. Bailie – ‘Report on the Health of the County Borough of Belfast, containing shocking revelations concerning ‘Sweating Labour’ in the linen industry, especially with the out-sourcing of piece work to largely female ‘home-workers’.

It caused a public outcry, exposing the heinous pay rates and working conditions of women as ‘homeworkers, where the standard rate of pay was ‘a penny per hour’, often less. For example, a woman who was paid one penny for hand sewing 308 dots on a cushion cover was fortunate to sew enough to earn 6d in a day. Another homeworker had to sew ornamentally 384 dots at one penny per handkerchief. Additional unpaid time and expense was incurred visiting warehouses to collect and deliver work, maintaining their sewing machine and the price of their thread. The report declared the most difficult cases were those where the house mother with a large family was the sole bread winner if her husband was unemployed or deceased. In many cases she would have to toil for very long hours far into the night, given such deplorable pay-rates just to afford the barest necessities of life.

Dr Bailie concluded: “…such underpaid labour must inevitably cripple…the good effects of any schemes of Health Reform. The underpaid, over-wrought physique of the sweated worker, with its weakened stamina, and lack of resistance to the inroads of disease, is undoubtedly one of the main causes of a high death rate.”

He also addressed the spread of tuberculosis among mill workers and their families and the high infant mortality rate. In Belfast in 1909 the number of premature deaths of infants under one-year-old in Belfast was 1,510, including 243 still births with many of these cases being young mothers who had been working for employers almost to the time of their giving birth and were, “most prevalent amongst women working in mills and factories.”

It found that they were in many cases entirely unfit for the kind of work they were doing: poor diet, insufficient nourishment, long exhausting hours of work in unsuitable conditions, having to work so close to the time of giving birth, and insufficient clothing were believed the likely causes for these deaths. Dr Bailie wrote, poignantly:

“Practically the whole of these underpaid workers are mothers, and the evil effects of their unremitting and ill-remunerated toil must be transmitted to the next generation.”

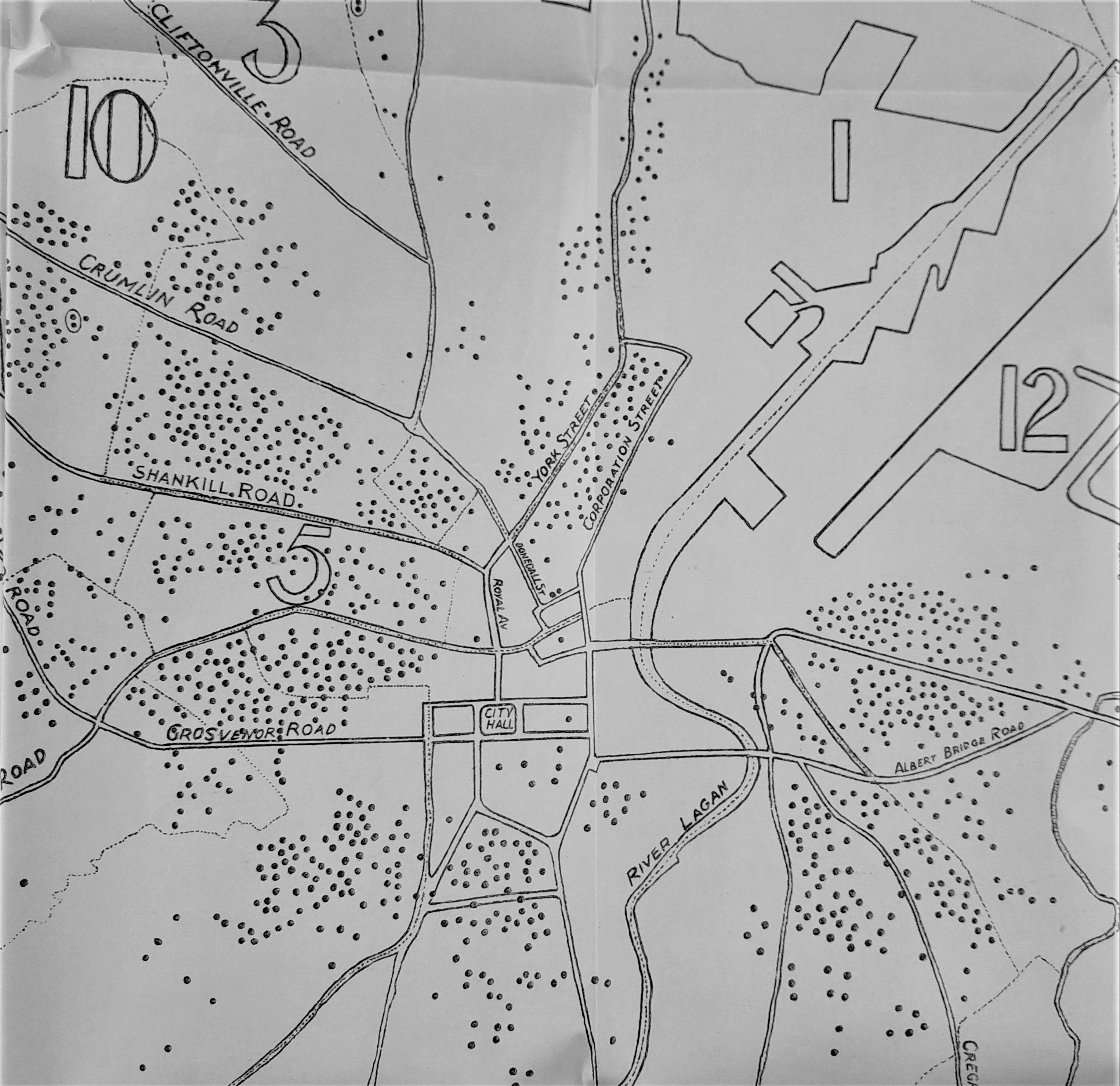

The prevalence of tuberculosis was equally shocking. Acquired through the inhalation of ‘flax dust’, it was a highly contagious disease that easily transmitted to others in close contact and in crowded poorly ventilated housing conditions. Tragically it was not unusual for entire families in working class areas of Belfast to be stricken with TB. Dr Bailie's report included a graphic map showing the distribution of tuberculosis cases in Belfast with 1,317 reported cases in 1909. The districts most severely affected were those where the textile mills were largely based – Falls, Shankill, Crumlin Road, East Belfast and mill districts near the city centre.

The Belfast Corporation’s Public Health Committee met on 25th August 1910 to discuss Dr Baillie’s Report. The Linen Merchant’s Association denied that large numbers of outworkers in Belfast, in effect comprised a ‘sweating industry’, adding “…we strongly resent the sweeping groundless charge made against us as a trade.” They claimed that employers couldn’t recruit a sufficient labour supply to complete the work inside the linen mills, and consequently they had to outsource piece work to homeworkers, if the industry was to complete orders. Wage rates they insisted, were the same for the same workers employed in the factory and rates of pay for the type of work undertaken were as high or even higher in Belfast than any other city in Ireland or Britain.

Distribution of reported cases of tuberculosis in Belfast 1909, DR H.W. Bailie, Report of the Health of the County Borough of Belfast for 1909 (pub' 1910)

The Belfast and District Trades and Labour Council supported Dr Bailie's findings regarding the ‘sweating industry’ and Mary Galway explained that if anything they were “considerably understated” and pressed for an investigation. Subsequently the Public Health Committee agreed to set up a special enquiry into the findings of Dr Bailie's report beginning with the issues of outworkers and ‘sweating’.

A packed public meeting was held at the Ulster Hall on September 14, organised by the Belfast Trades and Labour Council to protest and call for a government inquiry into Dr Baillie’s findings of ‘sweating’ in the linen trade. Joe Devlin in his address described sweated labour as equivalent to “…a system of chattel slavery in Ulster” adding that the manufacturers boasted to their customers everywhere that Belfast produced the finest linen in the world…“but what would those people think of that artistic work done by the nimble fingers of crushed and sweated women that their very bodies and souls were auctioned and bargained for in the market, and that they died at an early age, that prince merchants and lordly manufacturers throve…”

He would demand a government inquiry under the current 'Sweated Industries Bill’ at the House of Commons; the resolution was unanimously approved at the meeting.

The following year, the Belfast Evening Telegraph on October 25, 1911, published the address delivered in Belfast by Dr Todd Martin of the Presbyterian Church of Ireland, ‘Church, Politics, and Morality’. His views on labour organization were out of touch with the times and hardly sat well with desperate struggles for mere existence that was the life of the toiler and sweated worker, stating, “…The Church should make it clear that the rich man was neither better nor worse for his riches, and the poor neither better or worse for his poverty.”

“The sympathetic strikes of trades…showed how readily the antagonism between the working man and his employer might become a national danger. Should a leader arise with a genius for organization – one who could touch the imagination of the wage-earning classes, and gain their confidence and admiration – it might be possible for him to secure the cession of very extreme demands – demands that would absorb in increased wages the profits available for dividends, and leave their capital barren to the shareholders. In that, one of the aims of the Socialist could be accomplished…in either event the issue would be disastrous.”

James Connolly statue on the Falls Road

James Connolly understood the implications of such views for equality, social justice and the class struggle, writing in 1915, “Whatever class rules industrially will rule politically and impose upon the community… the beliefs, customs, and ideas most suitable to the perpetuation of its rule.”

Further dramatic developments occurred by October 1911, when the York Street linen mill, and others, introduced a system of fines in a drive to rapidly speed up production during the workers' shifts. Any worker who talked, laughed, sang, or even adjusted their hair during working hours was fined and bringing sweets or newspapers into the mill would result in instant dismissal. The result was a spontaneous strike. The Textile Operatives Society led by Mary Galway, refused to support the mill-girls in their 'unofficial' struggle against the new rules seeing it as “ill-advised”. The women desperately turned for assistance to James Connolly, then the ITGWU organizer. Consequently, following a meeting with Connolly, the ‘Textile Workers Union’ was established as part of the ITGWU.

Later the Belfast Evening Telegraph on 03 November, 1911, reported commentary where Miss Galway accused James Connolly of interference with the recent mill workers strike, describing Connolly intentions with labour organization as being akin to an “adventurer”. She called on the Trades’ Council “to condemn in the most emphatic manner the action of Mr Connolly in coming to a city to wreck a trade union that has done incalculable good.”

A wage claim was lodged by the strikers, as well as the demand to withdraw the new rules and practices. Earlier, Connolly had organised a 'non-sectarian Labour Band', which in solidarity paraded through Belfast raising collections for the strike fund. Two shillings a week was paid out to every striker. Connolly set about organizing more than one thousand spinners out on strike, holding outdoor and indoor meetings to raise funds, and recruiting women into the textile section of the ITGWU.

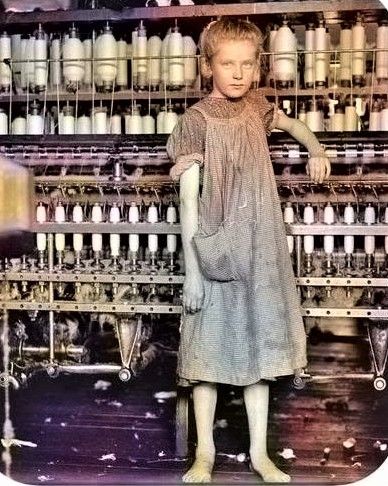

Belfast Mill Workers, barefooted, early 1900s. Courtesy of North &West Belfast Historical Photographical Society

For weeks, the strike remained solid but the employers refused to negotiate. In spite of sympathy and support for the strikers, financial aid was insufficient and Connolly advised the spinners to return to work and apply tactics of solidarity. If a girl was checked for singing, let the whole room start singing at once; if checked for laughing, let the whole room laugh at once; and if anyone is dismissed, ‘all put on your shawls and come out in a body.’ The strikers decided to return to work, singing and cheering, on the basis of ignoring the new rules. The employers were forced to give way – the new rules became unworkable and obsolete

In the case of tuberculosis, progress began to be made in the years ahead. In September 1913 the Belfast City Council formed the ‘Tuberculosis Committee’, and a scheme was devised and coordinated for the prevention, detection and treatment of tuberculosis. For every 100 persons who died from pulmonary tuberculosis in 1918 in Belfast, only 44 died of that disease in 1931, a reduction of 56 per cent in 13 years. This was put down to ‘prevention’ of tuberculosis rather than to cures, based on awareness raising campaigns, health prevention programmes and improved working conditions.

Many labour struggles lay ahead for the working classes. James Connolly and the Irish Textile Workers’ Union set about the task of organising 38,000 women and demanded that the entire linen industry be put under the Sweated Industries Act, which would fix a minimum wage for all employees. William Walker stated the reality of the situation in his column 'Belfast and the ‘Sweating Evil’, ‘Labour Leader’, September,1910,

“The conditions are appalling. No inferno of the future can have any terrors for our people equal to the torture which they endure at present, and that a way out may be found for the poor, and neglected of our community is the aim of the right-thinking section of our people.”

Brendan Muldoon ©2022