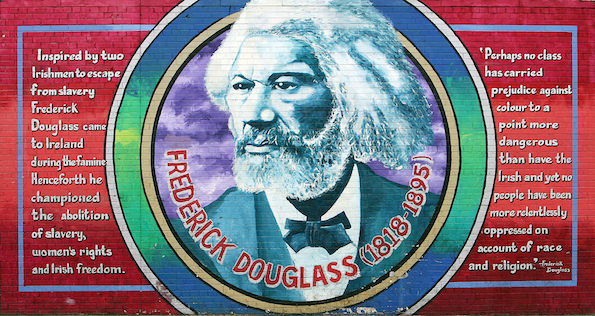

WRITING ON THE WALL: The International Wall mural honouring escaped slave Frederick Douglass who lectured in Belfast in 1845

Recent world events have deflected our attention from the Coronavirus pandemic. In a queue for a local Glengormley grocery store, I recently overhead two women discuss the aftermath of the death of George Floyd.

“It would put ye in mind o’ here in 1969,” one of them said.

“Aye, and I'll tell you what, thon boy wasn't as f***ing innocent as he looked. The policeman was only doing his job.” Thankfully at this stage the security guard waved the couple in and after skilfully snigging their cigarettes they departed the queue. Five minutes later I encountered them again, still in the full flow of historical reminiscences, as they threw their now relit cigarette butts on the footpath in front of me before boarding the 1D bus for New Mossley.

To say that I disagreed with the women would be an understatement but it made me think about the parallels and differences that exist today. The image of police batoning bystanders does bring back memories of Derry, Belfast and Newry in 1969 and 1970 when police violence was not uncommon. Parallels between the Irish and American Civil Rights Movements have been explored and people will differ on where their loyalties lie.

The recent removal of the slave trader Colston’s statue in Bristol leaves us thinking on what might have been but for the actions of a few enlightened people in Belfast towards the end of the eighteenth and throughout the nineteenth century. The removal of statues in Ireland has been an ongoing operation. Nelson’s Pillar removal was the best known and most successful in 1966 but subsequent efforts met with mixed results.

TRADITION: Cavehill, birthplace of Irish republicanism

At around 5 am on Hallowe’en, 31st October 1969, an explosion rang out at the grave in Co Kildare of United Irishman leader, Wolfe Tone. On the same night a boiler exploded at the railway works at Inchicore. As it was Hallowe’en the blasts were disguised as the sounds of fireworks filled the night air. Lights went out over South Dublin as an electricity sub-station innocently malfunctioned. Next day newspapers gave confusing accounts connecting the three events. Their error was uncovered when Belfast newspapers published a statement by ‘Captain Johnston’ on behalf of the UVF. He cited the blast at the grave of “the traitor Wolfe Tone” as the work of two UVF active service units.

In 1795, Wolfe Tone felt he had to leave Ireland. He decided to go with his family to America and he chose Belfast as his port of departure. One of the reasons he chose Belfast was that he wished to say farewell to his many friends there where he had been a frequent visitor over the previous four years and he wished to inform them that he was intending to seek help from the French. Sailings from Belfast to America were more frequent than from Dublin.

He arrived in Belfast in mid-May having booked his fare on the ‘Cinncinatus’ which was to leave Belfast port on June 13. It was for Tone both a sad and a happy time. He was glad to be back among his Northern friends but was also aware he would never see them again. They were the guests of Henry Joy McCracken. Tone later wrote, “But if our friends in Dublin were kind and affectionate those in Belfast, if possible were even more so.”

Parties and excursions were planned for Tone and his family almost every day and people who hardly knew them were keen to entertain them.

A day trip to Ram’s Island on Lough Neagh on 11 June was remembered by the Tones, Simms and McCracken families for years to come.

It was on one of those days that they climbed to the top of Cavehill. “I remember, particularly, two days that we spent on the Cavehill. On the first, Russell, Neilson, Simms, McCracken and one or two more of us, on the summit of McArt’s Fort, took a solemn obligation – which, I think I may say, I have, on my part, endeavoured to fulfil, never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country, and asserted our independence.”

The night before they left Belfast a farewell party was hosted by McCrackens. When harpist Edward Bunting began to play ‘Scaradh na gCompanach’ – ‘The Parting of Friends’ – Tone’s wife burst into tears.

Amongst those who provided support in Belfast for Tone was Thomas McCabe. A well-do Presbyterian, McCabe was one of the founding members of the Belfast Charitable Society, Clifton House, Belfast in 1774. In the 1770s, McCabe and John McCracken (father of United Irishman Henry Joy McCracken) installed machinery in the Clifton House, known then as Belfast Poor House, enabling it to become the first cotton spinning mill in the town.

Prior to the founding of the United Irishmen, McCabe was heavily involved in Belfast's liberal and radical community, being a leading figure in the city's anti-slavery circle. He clashed routinely with the plans of industrialist and president of Belfast Harbour Board, Waddell Cunningham and others to form the Belfast Slaveship Company which he wrote, “May God eternally damn the soul of the man who subscribes the first guinea.” In 1786, he prevented a slave-owning shipping company from setting up business in Belfast. These exploits led Theobald Wolfe Tone to style him as the 'Irish Slave'.

The United Irishmen were initially founded as a group of liberal Protestant and Presbyterian men interested in promoting Parliamentary reform. Tone put forward the case for unity between Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter. Their pamphlet was read by McCabe and a group of eight other prominent Belfast Presbyterians interested in reforming Irish Parliament. They invited Tone and his friend Thomas Russell to Belfast where the group met on October 14, 1791. It was there that the Belfast Society of the United Irishmen was formed, with McCabe as a founding member.

McCabe’s work opposing slavery was carried on after his death in 1820 by Mary Ann McCracken. She established the Women’s Abolitionary Committee and helped escaped slave Frederick Douglass tour Ireland to promote his memoir, ‘Narrative of the Life of an American Slave’. Right up to her death in 1866 she handed out anti-slavery leaflets to emigrant passengers heading from Belfast to America.

I very much doubt whether the men who carried out the explosion at Wolfe Tone’s grave in 1969 were aware of his political outlook or his love for all the people of Belfast. The bombing and destruction of 42 Catholic owned public houses in Protestant areas of Belfast in 1970 would give a clearer view to their thinking.