The late, great people's poet and rebellious bard Brian Moore had a famously sardonic ballad in praise of the 'Good Old Black and Tan', which was a tongue-in-cheek dig at the revisionists.

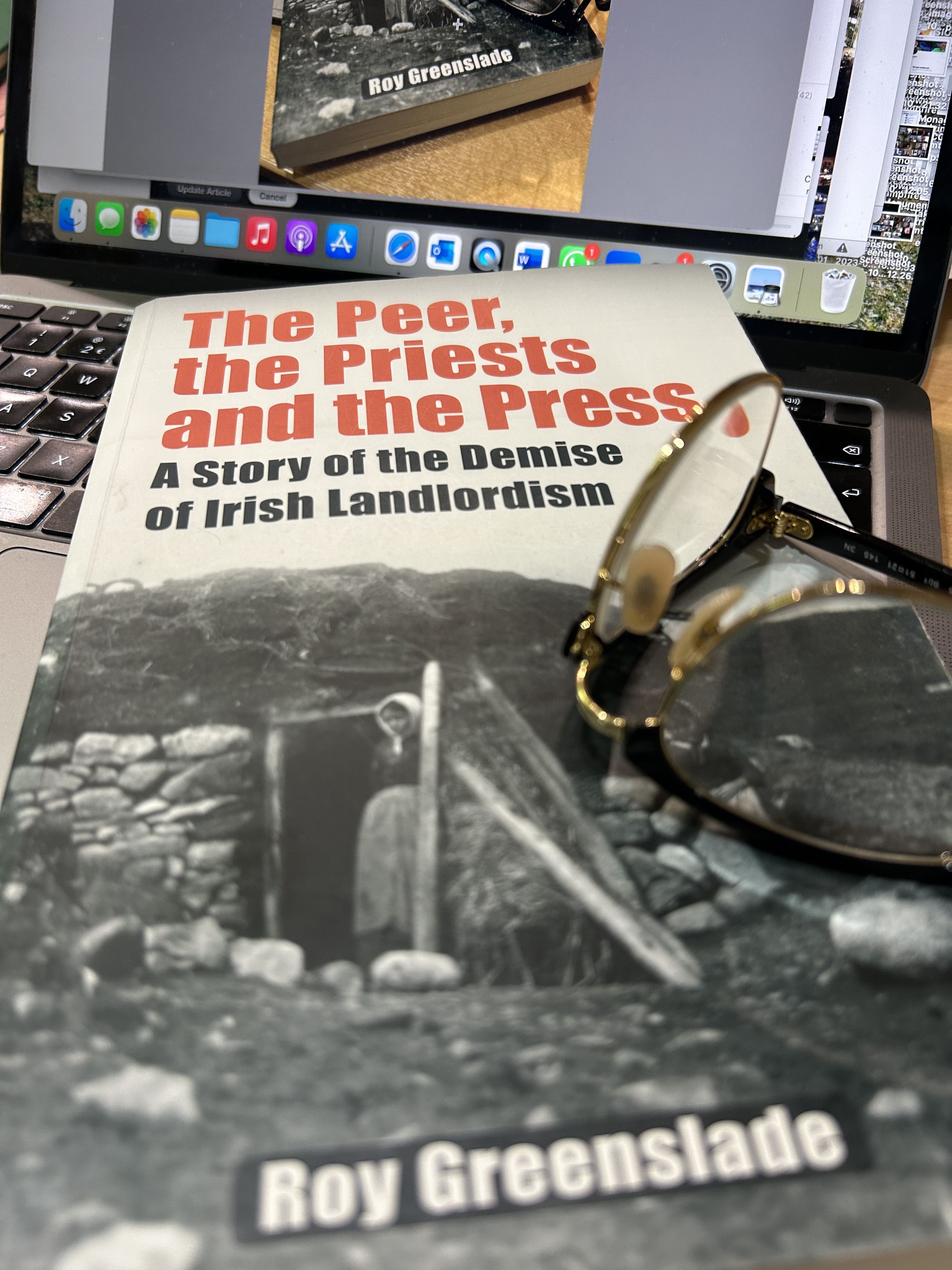

A book from the pen of the dean of journalism in these islands, Roy Greenslade, extolling the virtues of a 19th century Donegal landlord would have to be in similar satirical vein, you would think.

But you'd be wrong. For, despite the fervent hopes of this reviewer that the mask of Lord George Hill of Gweedore would slip in this compelling, fast-paced 200-page read, it turns out that this reforming landowner wasn't such a bad spud after all.

Indeed, it appears to be fact that when this former British Army officer and friend of the Royals first arrived in northwest Donegal in 1834, he was seduced by the epic scenery and genuinely felt moved to help tenants living in wretched conditions. Though, of course being the product of his times and class, he didn't connect their hand-to-mouth existence with the policies of their English overlords.

It's equally true, however, that Hill, as befits a member of the landed gentry, regarded his neighbours as "aboriginal Irish" who were "utterly ignorant and both mentally and physically degraded." But the record shows that the reforms he ushered in in order to boost the local economy and his advocacy for the community in face of famine ensured that, arguably uniquely in Ireland, none of his tenants died during An Gorta Mór.

A formidable self-publicist, Hill's fame spread far and wide with his name being held up in the British Parliament as that of a benign landlord whose generous actions staved off radicalism — a lesson, the British PM intimated, which should be heeded by his rapacious colleagues.

The eulogisation of Hill continued right up to the mid-1850s when he decided to deny local people access to hilltop lands traditionally used for grazing. Scottish sheep — and shepherds — brought in to avail of these lands were attacked by the Molly Maguires, a secret society formed to dish out some extrajudicial justice on behalf of the folks in the occupied territories.

THE JOURNALIST'S JOURNALIST: Roy Greenslade speaking at Féile an Phobail in 2012

The good lord's woes were worsened when the combative priests of Gaoth Dobhair lined up beside their flock to berate Hill and his landlord and government allies for forcing tenants into penury. They blasted his support for a dual tax penalty imposed on penniless tenants to compensate for the loss of the Scottish sheep and to cover the costs of the additional members of the constabulary dispatched from Dublin to keep order. The arrest of innocent local men for killing the imported sheep only deepened the divide between Hill, marooned in his Highlands style hotel (on the present site of An Chúirt hotel) at Dunlewey, and the "2,400 savages who occupied these bogs and mountains, living rather like the beasts of the field than human creatures", to quote the man from the Dublin Daily Mail. And singing from the same hymn sheet as the outspoken priests was crusading, Belfast-based journalist and publisher Denis Holland of The Ulsterman who came at Hill all guns blazing

Detailing the facts of the previously unilluminated life of Holland was a much tougher job for this biographer than recounting the oft-reported adventures of Hill. Nevertheless, this unputdownable book represents a long overdue telling of the story of a fearless publisher and reporter. Indeed, we owe Greenslade a debt of gratitude for bringing this scourge of anti-Catholic prejudice in 19th Century Belfast to our attention.

At the launch of Roy Greenslade's new book in Aras ui Chonghaile. pic.twitter.com/kEbuAnbZEG

— Danny Morrison (@molloy1916) December 18, 2023

To his credit, the sharp-tongued Holland gave Hill both barrels. After visiting the hovels of Donegal, Holland mocked Hill's saint-like status, devoting three major articles in his The Ulsterman newspaper to "that benevolent individual" that "model landlord" that "special blessing on two legs, sent by Providence for the comfort of the neglected Celts of the wilds of Donegal."

Holland's exposé shattered the claims of Hill's acolytes that his tenants were a contented lot well on their way to civilisation. "Jump down with me into the ditch and enter one of these huts," wrote Holland of the homes in Hill's utopia. "Here is a space, of some ten feet-square, the sole residence of this poor man, with his wife and four children — shared with them by the little ragged mountain cow..There is no chair, nothing to sit on but an old stool; and that heap of rags beside the fire-place, which will be the bed by and by. They are at dinner: what a horrid mess! Sticky potatoes and an abominable sea-weed...Yes, these are the tenants of my lord - these are the miserable beings whose sweat and labour are coined into rent for the master...and that the landlords who dwell in luxury on their unceasing labour should be heralded to the world with sounds of praise and fame!"

OVERVIEW: Prof. Breandán Mac Suibhne speaking at the launch of 'The Peer' in Áras Uí Chonghaile

As agrarian protest against landlordism heightened in the 1850s and 1860s, some of Hill's neighbours deployed Trevelyanesque tactics against their struggling tenants. John Adair of Derryveagh, adjacent to Gaoth Dobhair, evicted 244 people from their homes in 1861. Lord Leitrim, Hill's neighbour to the north, was equally barbarous, meeting an apposite end in 1878 when he was shot and then clubbed to death.

This revelatory read, therefore, covers both the glamorous heyday, as the loyal press would have it, and the inglorious descent of landlordism in Ireland. Along the way it sheds light on the fighting fathers of Gaoth Dobhair parish — clerics in the Fr Des mould — who raised the cries of their tormented parishioners right to the ears of the genteel dastards in Westminster.

Greenslade, who in 1991 (unknowingly) bought Hill's home in Ramelton, delivers mixed judgement on the one-time owner of over 20,000 acres of Donegal. Contradictory as it may be, he concludes that Hill was both a benefactor and a brute. He was, this thorough study proves, a man genuinely bent on, in his paternal manner, "improving and elevating a tenantry whose civilisation was...not far above Central Africa's" (to quote his local pastor on Hill's death in 1879). In later life, Hill, unforgivably, declared the Great Famine a good thing for the Irish. And of course, with his fellow landlords he effectively controlled the police and the courts, placing him up to his neck in a system built on injustice and repression. A savage and uncivilised system, some might say.

And yet, and yet. Perhaps 150 and more years on we can forgive.

Didn't Hill for all that disdain for the natives, learn Irish and ensure his children too were tutored in Irish? Didn't he makes thing better for his stricken tenants even if he didn't create the heaven on earth in Gaoth Dobhair hailed by his adoring publicists.

Our tortured history, it turns out, certainly in this case at least, may not be as black and white as we would wish it to be. Indeed, dare I say that it may not even be as Black and Tan.

'The Peer, the Priests and the Press' A Story of the Demise of Irish Landlordism. Roy Greenslade, Beyond the Pale Press. £16. Available from the publishers or from local bookshops including An Ceathrú Póilí.