Nicola Sturgeon is serious. That, at least, is the big pitch Scotland’s First Minister is making in the crucial last few days of this election campaign.

The SNP leader uses the word over and over again. She is personally “serious”, she insists more or less whenever a microphone is in front of her. The times are “serious”, she adds. Her opponents, the unspoken logic continues, are not. They, she says, “play games”.

Every vote counts. If you want a First Minister and government ready to get back to work to lead us through Covid and build a better country...please cast #BothVotesSNP on Thursday pic.twitter.com/UrkWimUNBE

— Nicola Sturgeon (@NicolaSturgeon) May 1, 2021

Ms Sturgeon is, indeed, the only politician with a “serious” chance of being first minister after Thursday’s national poll for Scotland’s parliament, Holyrood. But she is not just aiming to win, she is aiming to win big.

Why? Because Ms Sturgeon thinks - you guessed it - Scotland should start to “get serious" about independence. But to do that — to even have a chance at a second referendum — she needs an undisputed mandate.

Final stop of the day is stunning, beautiful, Glencoe.

— Chris Jones (@C9J) May 2, 2021

🗳 #BothVotesSNP 🗳 pic.twitter.com/8etiQ0L20Y

Ms Sturgeon can probably be quite confident that her SNP and its sometimes allies, the Scottish Greens, can secure an overall majority in Holyrood. But can her party get half the seats on its own? Maybe.

Two polls this weekend put the SNP’s prospects of an overall majority and support for its core policy of independence on what newspapers like to call a 'knife edge. One, by BMG Research for The Herald on Sunday, suggested the Nationalists would be in a position to get 68 of Holyrood’s 129 seats. Another, for Panelbase in the Sunday Times, put the SNP on a razor-thin majority of one with 65 seats.

It can be hard to calculate seats in Scotland because of all the variables in the country’s two-vote system. But the SNP is at 49 per cent in both polls on the first ballot, the local constituency one, and this should be enough to sweep much of mainland Scotland with just a handful of seats in opposition hands. Unionists will have to fight for a share of second votes, on regional lists.

Pro-UK voters have one shot to stop another referendum and there is only one way to do it. @ScotTories are the only party strong enough to stop indyref2 and ensure our next Parliament is 100% focused on the recovery from Covid. #peachvotetory pic.twitter.com/k8ddQer2HK

— Douglas Ross MP (@Douglas4Moray) April 30, 2021

The latest polls also shows a country where independence and union are more or less neck and neck. BMG for The Herald had a 50-50 split; Panelbase put Yes, for independence, ahead by just 52-48.

This election has not been easy for the SNP. Both the party — and independence — had been safely ahead in the polls. They saw similar leads squandered in 2016, at the last Holyrood election when they scraped home just short of an overall majority.

Some unionists have been taking heart that they are shaving away at that nationalist advantage this time too. There are a few theories for why this might be. Alex Salmond, Ms Sturgeon’s predecessor as SNP leader and first minister, has re-emerged, launching a new party, Alba.

His party is polling very low but he might get a seat or two, the most recent surveys suggest. But Mr Salmond is by far Scotland’s least popular politician and, plenty of politics watchers suggest, he may be putting swing voters off independence and the SNP.

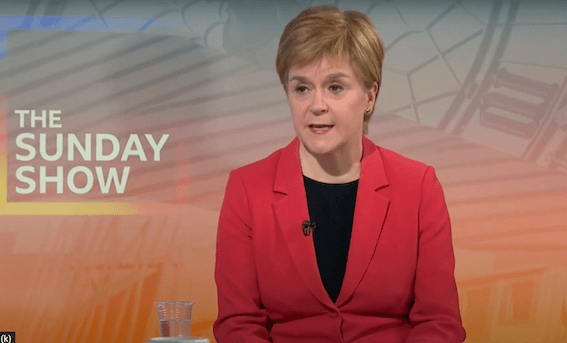

"This country needs serious leadership for serious times” @NicolaSturgeon powerful and clear on the BBC Scotland Sunday Show.

— Kirsten Oswald MP (@kirstenoswald) May 2, 2021

It must be #BothVotesSNP on Thursday to deliver the serious leadership Scotland needs, and make sure Scotland’s recovery is in Scotland’s hands. pic.twitter.com/u5MGzNvQVR

There are other issues too. Ms Sturgeon had been riding high on her pandemic response and the fall-out of Brexit. But the campaign has raised all sorts of knotty issues around independence and the EU, about currency, borders and the future of the financial services industry.

The first minister last week told The Irish Times that Northern Ireland’s arrangements for EU trade could be a model, a “template”, for an independent Scotland to rejoin the bloc and still trade with England. Her opponents said this was “delusional”. However, Ms Sturgeon has acknowledged that Brexit does present “practical difficulties” for trade with a rump British state, usually called rUK in Scotland, after independence.

For some nationalists, this all a bit deja vu. Unionists, they say, talked up problems about independence ahead of 2014 and they are doing so again now. This campaign of negativity was called Project Fear.

Some pro-UK politicians have been whistling some familiar tunes. They, for example latched on to an announcement from NatWest, the huge conglomerate which includes the once massive Royal Bank of Scotland, that it would pull its HQ out of Edinburgh if Scots voted to leave the UK. Why? Its balance sheet, its chief executive Alison Rose said, was too big to be regulated in a country of Scotland’s size.

Ms Sturgeon said she did not recognise this rationale. But these familiar themes clearly vex the SNP. Take too talk of the future of the Clyde Naval Base, home of Britain’s Trident submarines.

Banks and bombs are electorally important, including in the country’s two most marginal seats, Labour-held Dumbarton and Tory-held Edinburgh Central. The SNP almost certainly has two win these two constituencies to get its overall majority. They are, as pundits say, the “ones to watch” as results slowly filter through over this coming weekend.

Ms Sturgeon has come under fire for not having full answers on currency or borders or defence after independence. She has also faced criticism for supposedly obsessing about independence during the pandemic. She retorts that this line of attack is not logical. There will, she says, be a prospectus for independence. But not now. First, Scotland has to get out of the Covid crisis.

Just had @jackiebmsp @ScottishLabour at the door. I assured Jackie she is getting our vote. There were only 109 votes between Labour & SNP last time. Losing Jackie in our area doesn’t bear thinking about. Even if you don’t normally vote Labour lend her your vote this time 🌹🇬🇧 pic.twitter.com/lUQ7FZizBM

— Mrs F (@taf0650_f) April 29, 2021

Will this be convincing? We’ll know within a week. Thursday’s elections are not a referendum, she told the Sunday Show on BBC Scotland. But they are, perhaps, a referendum about a referendum.

Because a showdown is coming about whether Scotland has the right to decide its future or not. Ms Sturgeon on the BBC was asked to say when a vote will be. Her response summed up her campaign message.

“It shouldn't be me as an individual politician, no more than it should be Boris Johnson as an individual politician who decides Scotland's future, it should be the people of Scotland, it is a basic principle of democracy,” she said.

“My focus though will be on continuing to steer us through Covid, and then yes, giving people the right to decide what kind of country do we want Scotland to recover to and who should be in the driving seat. I don't want Boris Johnson making the decisions about the country Scotland will become.”

Nicola Sturgeon is serious. Or so she wants us to believe. And Boris Johnson - goes her subtext - is not.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak: "The uncertainty of another referendum must be stopped to finish the job on COVID-19".

— Stephen Kerr - Scottish Conservative & Unionist (@RealStephenKerr) May 3, 2021

This means no hanging Referendums over us, as the SNP want to do. They need to be off the table. Only the Scottish Conservatives will guarantee this.#PeachVoteTory pic.twitter.com/lRoWfCN0Ek