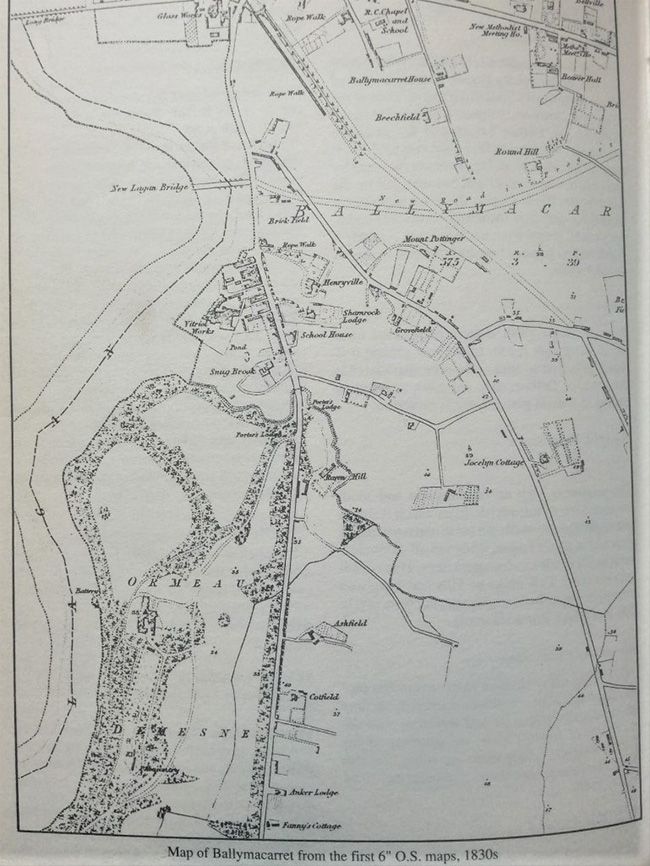

LOCATED on the opposite east side of the River Lagan in County Down, Baile Mhic Gearóid – McGarrett’s townland – in the early 1830s was an isolated place of 428 acres, surrounded by vast swathes of countryside, settled with some mansions and numerous cottages, occupied mainly by handloom weavers, who provided the staple industry of the locality, defining its cultural traditions and heritage. It was here that John Keats, the famous poet, passed, whilst walking from Donaghadee to Belfast in 1818.

“We heard”, he wrote to his sister, “on passing into Belfast through a most wretched suburb that most disgusting of all noises, worse than the bagpipes, the laugh of a monkey, the chatter of women, the scream of a macaw – I mean the sound of a shuttle.”

The community of handloom weavers was settled at Ballymacarrett from at least the mid-18th century; then a sparsely populated settlement, in 1781 having 419 inhabitants, 1791 – 1,208 inhabitants. The 1821 census revealed a population of approximately 3,000 inhabitants, increasing in 1830 to about 5,000. It’s religious composition in 1831 was Established Church 2,142, Roman Catholic 2,219, Presbyterian 1,229, others 255, Total, 5,168.

The peculiar local position of the townland may, in part, account for the poverty and misery of its inhabitants; for, though within a stone throw of the town of Belfast, it is yet no part of it – it is in a different county, and has, hitherto, been free from borough taxation

Handloom weaving was a highly skilled and established cottage industry across Ireland in the 18th and 19th centuries, based mainly on fine cotton cloth weaving and later linen production during the first half of the 19th century when many cottage weavers moved over to linen weaving. Even with mechanization and industrialisation and changed working practices both domestic cottage and textile mill production co-existed for a long period in the 19th century.

Cottage weaving was normally a whole family affair with parents and children involved in all stages of cloth production, spinning, weaving and bringing the finished cloth to market in Belfast to sell; some families also did ‘piece work’ for employers but all their work was extremely poorly paid. In 1823 a handloom weaver in Ballymacarrett might expect payment of one shilling per day for his family’s work, often only three shillings per week after working twelve-hour days.

From the early 19th century the weavers at Ballymacarrett lived in little colonies at Scotch Row, Club Row Loney, Near Club Row, Far Club Row and Pigtail Row, Gooseberry Corner, Campbell’s Row, Doggart’s Row and elsewhere. In April 1842 there were approximately 207 families in Ballymacarrett engaged in weaving, possessing 586 looms. The inhabitants lived in rented rundown cottage homes and the area had an absence of planned drainage networks and channels; like other suburbs outside Belfast it did not benefit from the sanitary regulations that applied to the Borough of Belfast. Dr A. G. Malcolm in his 1852 report, ‘The Sanitary State of Belfast’, said “a more neglected portion of the town cannot be well conceived.” One major progressive step to alleviate suffering and consequences of poverty on health was the establishment of a Medical Dispensary in Ballymacarrett in 1833.

Cycles of economic downturn in the textile trade, unemployment, poverty wages and appalling living conditions, placed pressures their community simply couldn’t endure by the mid-19th century. The Rev. J. H. Potts stated the essence of their problem at a parish church meeting on February 16th 1830, “Ballymacarrett had not within itself an intrinsic means for the permanent support of its population.”

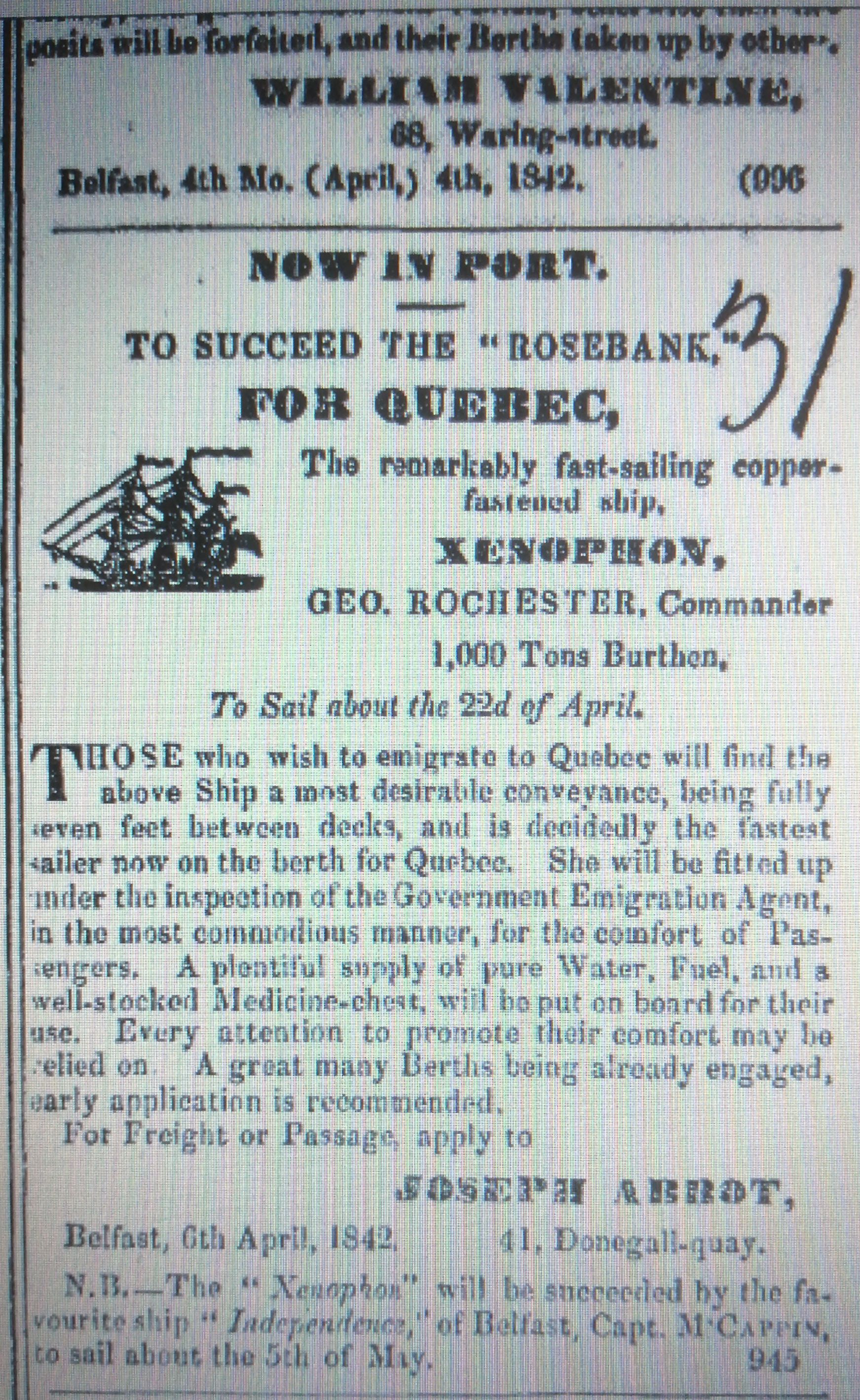

Adverisement for 1842 of Passenger Emigrant Vessel 'Xenophon' to Quebec from Belfast

John Boyd, Secretary to the Ballymacarrett Relief Committee explained in a public letter in January 1847 the dilemma for Ballymacarrett:

“The peculiar local position of the townland may, in part, account for the poverty and misery of its inhabitants; for, though within a stone throw of the town of Belfast, it is yet no part of it – it is in a different county, and has, hitherto, been free from borough taxation. The consequence has been that it is, beyond all question, the poorest suburb of Belfast, being densely peopled by the very lowest class of weavers and other operatives…whose small houses are, in most instances, receptacles for paupers of every description, until, out of a population of about six thousand, three-fourths, at the very least, are in a state of sickening poverty…”

At critical periods of economic downturn and the effects of the Great Famine, public appeals for financial assistance were made to support assisted emigration programmes for the handloom weavers to relocate to Canada to find a better life; appeals were made in 1842, 1846 and 1863. It’s unclear how many weaving families emigrated to Canada during these years but on the 24th May, 1842 the Belfast Newsletter revealed that 20 to 30 families were supported to emigrate by a contribution in Belfast of £150.

In 1862 a Ballymacarrett Relief Committee was formed in Belfast to raise funds to alleviate the ‘immediate’ distress of the weavers; the Newsletter established a separate ‘Newsletter Fund’ to attract funds for ‘permanent’ solutions including financing the weaver’s emigration to Canada and elsewhere. Their fund initially financed the passages of 90 persons from the weaving communities of Ballymacarrett and Belfast to Queensland, Australia in 1862 and in February 1863 appeals for public donations increased for assisted emigration for the handloom weavers. Their report of weaver’s pay rates, working hours, the nature of their trade and working lives revealed wage rates in 1863 as compared to 1823 were such that the most that could be made in a week was five shillings 6½d but frequently only three shillings 1½d per week. Its final comment captured the harrowing reality of their existence: “Handloom weaving is little better than a slow process of starvation.”

In April 1863 the Newsletter reported 465 persons, of about 107 families from the weaving community, still in acute distress from Belfast and Ballymacarrett. They hoped with ongoing fundraising to get most, passages to Canada; ongoing arrangements for a number were already in progress. Later in June the Belfast Board of Guardians controversially refused to strike a rate to raise funds to support the weaver’s emigration plans, effectively abandoning them; private fundraising continued unabated.

On the 27th May 1863, 254 handloom weavers and their families from Lisburn departed from Belfast aboard the ‘Old Hickory’ to emigrate to Philadelphia in America for a new and better life, funded by the Lisburn Relief Committee. Their widely publicised assembly in Belfast, supported by thousands of well-wishers must surely have been a great sight of hope and inspiration for the weavers of Belfast and Ballymacarrett.

The horrors of the Great Famine are well known and Ballymacarrett like Belfast experienced appalling distress. On April 10th 1846, the Newsletter published an appeal by residents of Ballymacarrett:

“We, the undersigned inhabitants of Ballymacarrett have personally inspected the dwellings of most of the weavers in that locality, desire to bear testimony to the extreme destitution of which we have been eye witnesses. In one entire range of houses called Campbell’s Row, we find seven-eighths of the looms idle, and many families in a state of almost complete starvation… more than 300 families have already received relief in provisions from the Local Committee…we are obliged to appeal to the benevolent and wealthy inhabitants of Belfast…to enable us to open a Soup Kitchen, where nutritious food may be supplied to all who have not means to procuring it for themselves...”

Our only hopes of success are grounded upon the belief that the public of Belfast and neighbourhood will contribute to bring about so desirable an end. This view is supported by the fact, that about four years ago, a society, composed of the weaving population of the same locality, were sent out to America by private subscription, and should we obtain our object, our expectations are very great from the encouragements that we have received from time to time from the former society, who are all in comfortable and flourishing circumstances, some of them having remitted money enough to take out friends and relatives left behind in this place...”

The Newsletter commented, “We have ourselves observed the wretched state of the dwellings of these poor people…no one can pass through the place, without being satisfied of the utter misery of a large portion of the inhabitants. That such misery could exist in the neighbourhood of a rich and flourishing town, like Belfast, is a lasting disgrace to our community.”

Map of Ballymacarrett in the 1830s

On May 15th 1846, the Newsletter published a letter indicating that thirty weavers from Ballymacarrett had formed a society to raise funds through public appeal for assistance in financing the emigration of their families to Canada.

“Our only hopes of success are grounded upon the belief that the public of Belfast and neighbourhood will contribute to bring about so desirable an end. This view is supported by the fact, that about four years ago, a society, composed of the weaving population of the same locality, were sent out to America by private subscription, and should we obtain our object, our expectations are very great from the encouragements that we have received from time to time from the former society, who are all in comfortable and flourishing circumstances, some of them having remitted money enough to take out friends and relatives left behind in this place...”

The Banner of Ulster published a letter on February 2nd 1847 from John Boyd, Secretary to the Ballymacarrett Relief Committee, appealing for public donations to help the committee’s relief programme, stressing that the dreadful circumstances in Ballymacarrett were progressing with frightful rapidity, starkly comparing the scenes there with some of the worse to be found in the south and west of Ireland such as Skibbereen and Bantry. He added that a Soup Kitchen was opened up at an expense of £20 per week and small quantities of coal were distributed to help the poor stay warm. Between 1,100 and 1,200 individuals received rations from the soup kitchen daily, but funds were running out and they were anxious of being left without means of relieving the wants of a starving people.

He explained that the Ballymacarrett Relief Committee felt they should be better supported by Belfast General Relief Committee Funds and concerned that it was distributing large donations throughout Ireland rather than focus sufficiently on their own neighbourhoods and adjoining districts. Boyd warned of the consequences if Ballymacarrett was not supported from Belfast’s General Relief Funds, “...the merchants of Belfast will have themselves to blame, if they are, ere long, visited by the pestilential fever which is now spreading on this side of the river, and which, if not soon checked, may cross into the town, and produce equally, in its lanes and terraces, consequences the most deadly and disastrous.”

The seriousness of the fever outbreak in Ballymacarrett was reported by the Vindicator on June 5th 1847.

“On Tuesday last a man named Thomas Hopkins was found in a state of nudity, lying in the street, and suffering from a violent attack of fever…Sergeant Mc Intire, of the constabulary…had the unhappy creature removed to the Fever Hospital. On Wednesday he visited a house occupied by a man named Templeton, and on-going upstairs, found in a wretched apartment, no less than five individuals, lying without even the comfort of straw upon the boards, and all infected with a malignant fever. In addition to this horrible state of things, he discovered a dead child lying stretched besides its mother! The whole family were sent to the hospital.” Attending, Dr Murray stated that in the previous ten days he had sent 91 fever cases to the Fever Hospital in Belfast from Ballymacarrett. The Banner of Ulster on June 12th 1847 observing that approximately 1,500 fever cases were in Belfast hospitals, added, “We understand fever is very prevalent in Ballymacarrett; and immediate steps ought to be taken to preserve the public health there.”

Knock Burial Ground where many people who lived in 18th and 19th century Ballymacarrett are buried © Copyright Rossographer and licensed for reuse under creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0

Renewed efforts were put into finding funds for assisted emigration to Canada for the Ballymacarrett weavers and those in Belfast districts. Tragically emigrant passengers knew not what awful horrors lay ahead of them during these Famine voyages. Many died at sea from fever in the deplorable conditions of the holds of the ‘Coffin Ships’. Irish emigrants were placed in quarantine at Grosse Island on the St Lawrence River, 30 miles from Quebec, many remained on board scores of vessels anchored off shore. Thousands died of typhus fever before ever seeing Quebec or any other part of Canada and are buried on Grosse Island.

A Letter from the Archbishop of Quebec, ‘Emigration to Canada’ addressed to the Catholic Bishops of Ireland was published by the Belfast Vindicator on 3rd July, 1847, providing a reality check. He appealed to the clergy to use their influence to dissuade as many as possible from seeing emigration to Canada as a desirable plan, as untold hardship, suffering, and frequently premature death were often the likely outcomes.

Later the Freemans Journal in Dublin reported in February 1848 on assisted emigration from Ireland to Canada in an article titled ‘The Emigration Tragedy’, based on the Report of the Montreal Relief Committee. During 1847 of 100,000 who emigrated from the British Isles to Canada, mainly Irish, for a new and better life “a full one quarter of the whole have been swept from existence” i.e. 25,000 deaths from contagion and disease. 5,000 died enroute on the ships and buried at sea, 3,389 died at Grosse Island, 1,187 at Quebec, 5,862 at Montreal and thousands in other locations.

It’s unknown if any handloom weavers and their families from Ballymacarrett or Belfast who managed to secure their passage to Canada met a similar fate.

Ballymacarrett endured and did eventually recover. On February 10th 1893 the Newsletter reported on a three-day bazaar to raise funds for the completion of the new Ballymacarrett Parish Church.

“No part of Belfast has grown with such marvellous rapidity as Ballymacarrett. A few years ago, it was merely a village consisting of long rows of whitewashed cottages extending from Queens Bridge to Connswater...Now it’s the largest suburb of Belfast and is a veritable town in itself.”

Change over time through mechanisation and industrialization ensured that the work of the cottage-based handloom weaving families would come to an end. In 1863 an official at a Town Hall Meeting in Belfast claimed there were 4,000 handloom weavers in a 10 mile radius surrounding Belfast. The last handloom in Ballymacarrett was dismantled in 1906 when the poet John Keat’s ‘most disgusting of all noises, the sound of a shuttle’, was to be heard no more.

Brendan Muldoon©2021