I had the privilege of attending many of the debates and discussions which are a unique and vital part of Féile an Phobail. Well done to all the participants and in particular to the organisers and the stewards who ensured that everything worked smoothly. Thanks also to the venues which welcomed us all.

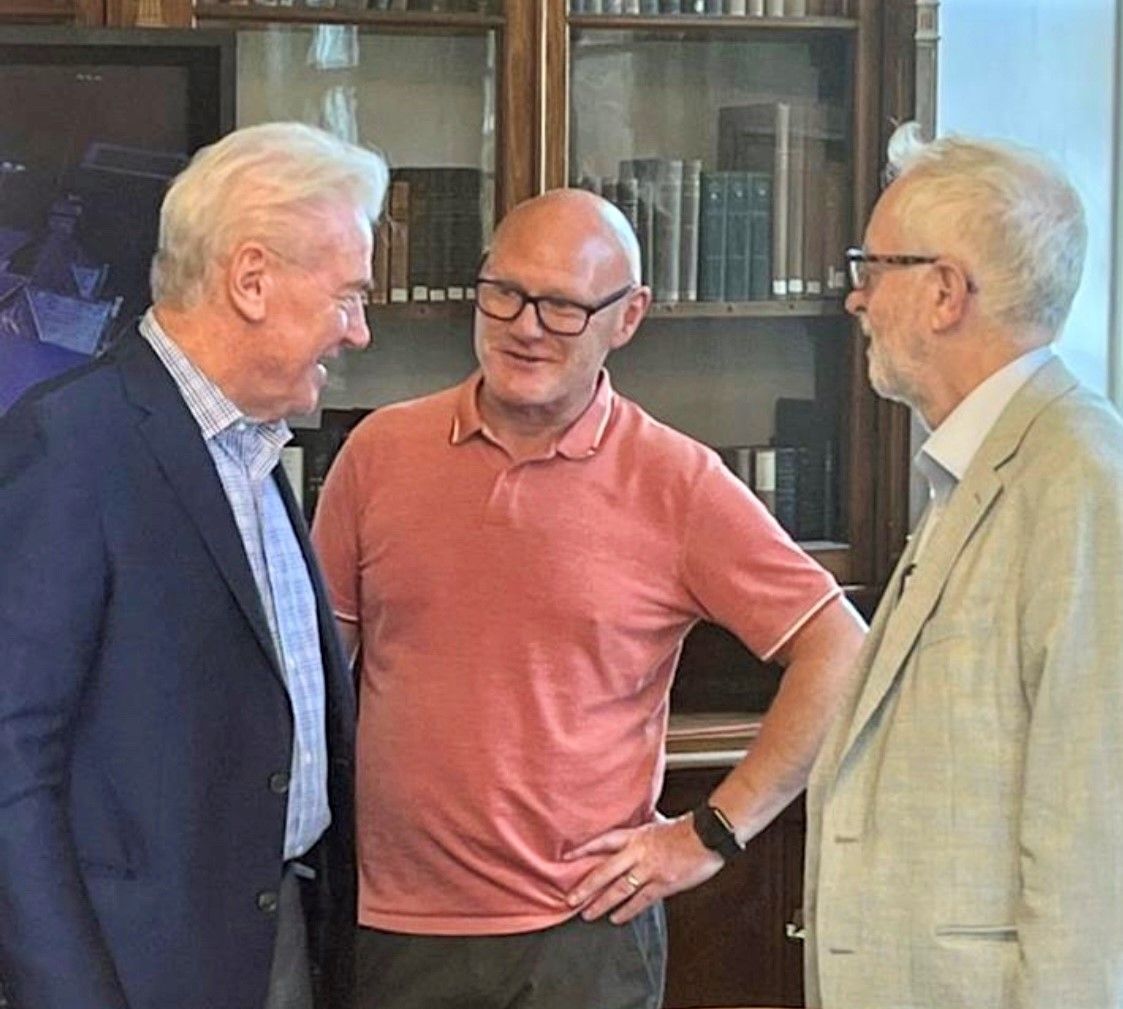

I want to touch briefly on the remarks made by Terry O'Sullivan and Jeremy Corbyn at separate events, particularly on the importance of organising civic society. Jeremy, a former leader of the British Labour Party and Terry, the General Secretary Emeritus of The Laborers' International Union of North America, are wonderful advocates for the imperative of organising social and political movements to bring about deep rooted and positive change.

How different Ireland would be — how different the world would be — but for the lives stolen from us in the executions of those who led the Easter Rising of 1916.

— Jeremy Corbyn (@jeremycorbyn) August 4, 2023

My tribute to James Connolly at #Feile35.pic.twitter.com/CG6bSH2GXg

For all of the differences in their two countries the need to organise people is a common thread in their work. That and a fierce commitment to equality and social justice. And a love for Ireland. We are lucky to have them as allies and friends.

This columnist is a long time believer in the power of people, properly organised, strategic and strong in their beliefs and values. There are lots of current and historic examples of the changes brought about by such movements in Ireland and other parts of the world.

Political change will be more meaningful, deep rooted and advanced if it is led by informed and committed citizens. Shaping a fair society is too important to be left solely to politicians. Of course, public representatives have an important role including the delivery of legislative and underpinned guarantees of peoples rights once those rights have been won. But they are unlikely to be won without popular struggle. Progress is dependent on that. Activism is central to this. And activism works.

Jeremy quoted James Connolly to make this point. In an article “The Economic Basis of Politics,” Connolly argued "an effective political force" had to have its origins "deep down in the daily life of the people, not in the brains of some half dozen gentlemen in parliament."

On behalf of #LIUNA, retired GP Terry O’Sullivan at the @JamesConnollyVC in Belfast, Ireland at the unveiling of the plaque in memory of Honorary LIUNA member and Irish Republican Rita O’Hare. pic.twitter.com/59Dw2mmKVd

— LIUNA (@LIUNA) August 3, 2023

For his part, Terry O Sullivan told us that the "labour movement is once again on the rise throughout North America ….a new generation of workers is beginning to understand the power of activism."

He outlined how LiUNA organised labourers, mostly immigrants with little rights or protections. He, like Jeremy, spoke of the importance of solidarity. "An injustice to one is an injustice to all." He said: "The trade union movement is the single most effective anti-poverty programme ever devised."

Féile An Phobail is a great example of activism and community empowerment. It is inclusive grassroots democracy in action. On all fronts. Cultural, educational and artistic. The creative arts for the many. And it's enjoyable. Full of hope and colour and vitality.

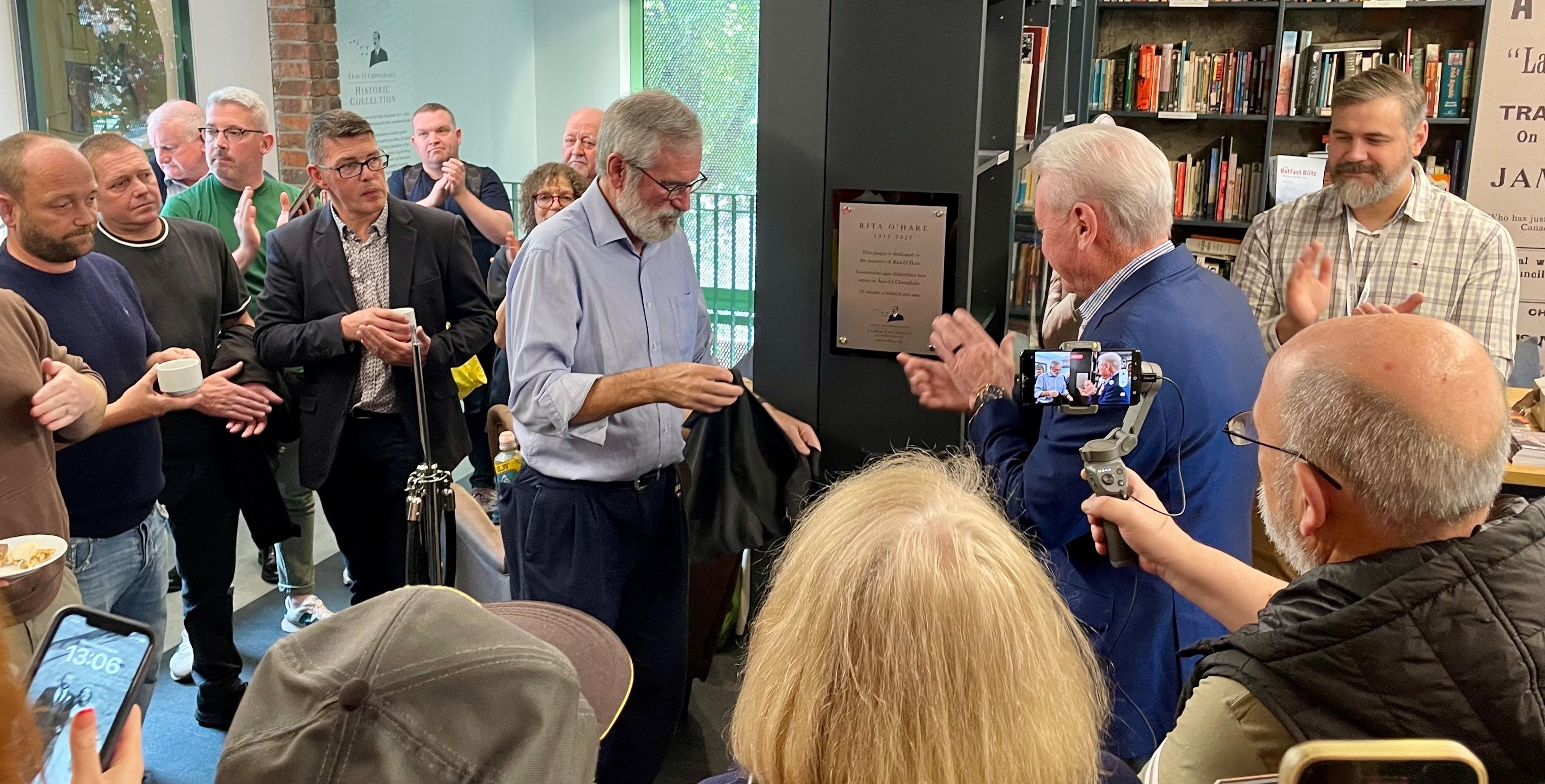

Unveiling the plaque dedicated to Rita O'Hare.

So activism works. Creating a new Ireland means ending the union with England. There is now a way to do this. Activism is crucial to secure that goal.

James Connolly believed in the reconquest of Ireland by the Irish people. I believe in that too. So did Bobby Sands. Bobby wrote: "The day will dawn when all the people of Ireland will have the desire for Freedom to show. It is then we will see the rising of the moon."

So there is space for all progressives in the work to shape an empowered movement for a new shared Ireland. As Jeremy Corbyn said: "The planning, the preparation, and the consultation needs to take place beforehand so that people know what the choice is. What exactly is the proposition they are voting for. This requires serious and novel engagement. Every available resource and expertise should be pooled. Citizens Assemblies, local forums and civic consultation should be utilised. That work will be done here in Ireland obviously."

He went on to explain the role for people in Britain. Terry did the same in relation to North America. That is important. But few of us will have a contribution to make there. Our work is where we live.

And it is clear what we have to do here. Change is underway. Let's be active in shaping and deepening that change. It's time to get involved. It's time to move beyond talking about it. Or leaving it to others. There is a role for everyone. It's time to be an active citizen. It's time for campaigning, organising, for democratic empowerment. Let's do it. Be an activist.

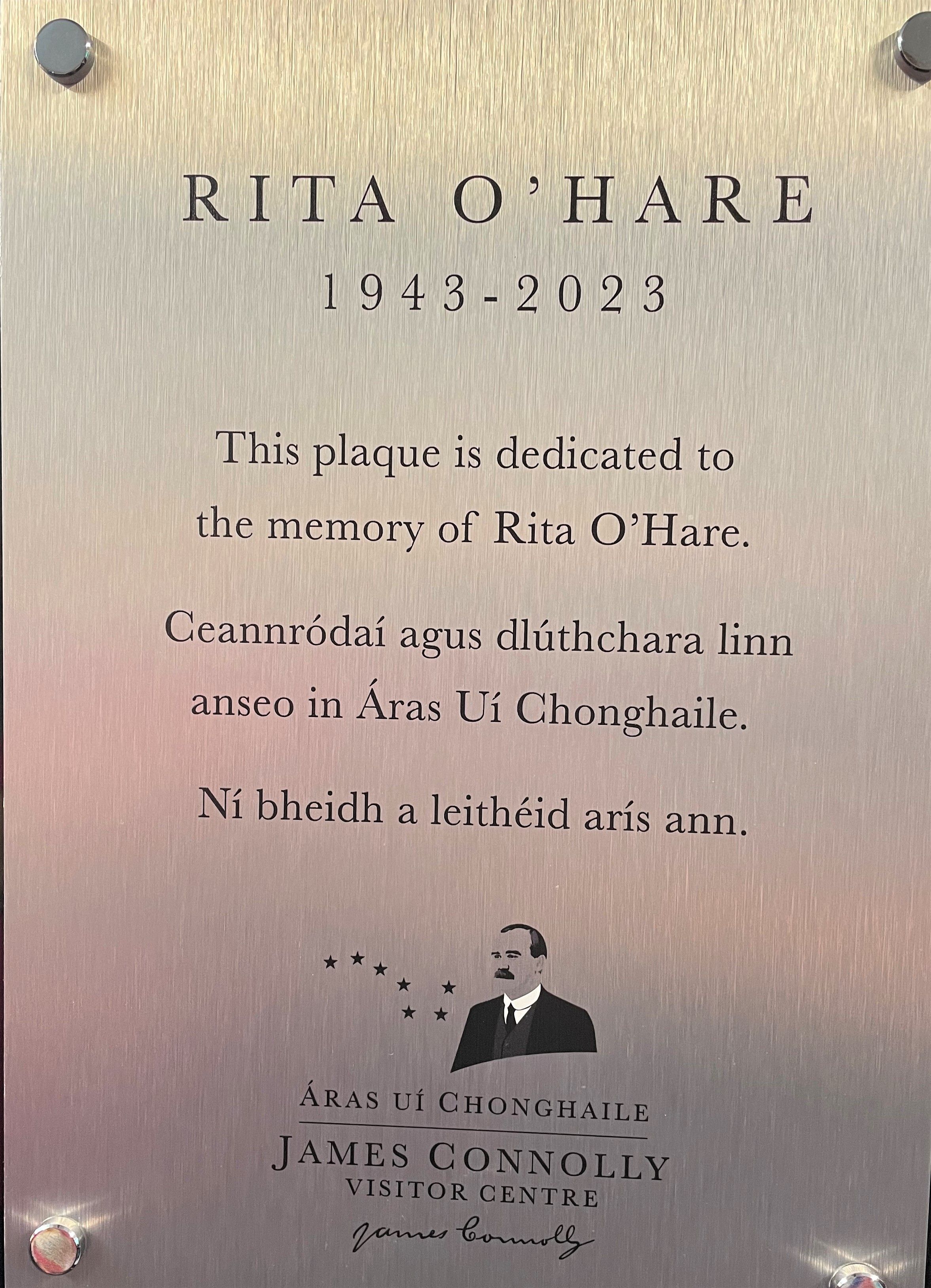

Rita O’Hare and Áras Uí Chonghaile

Áras Uí Chonghaile on the Falls Road was formally opened by Uachtarán na hÉireann Michael D Higgins in April 2019. Through its historic artifacts, art work, innovative technology and story-telling it teaches us of the life and times of James Connolly, the 1916 executed leader.

Last Thursday, a large number of family, friends and comrades of Rita O’Hare came together to unveil a plaque in Áras Uí Chonghaile in her memory. Without her unique contribution this important project might never have succeeded.

When Belfast activists first discussed the possibility of opening a centre named after James Connolly they faced many difficulties. Finding the necessary funding was a particular challenge.

It was into this critical gap that Rita O’Hare stepped. As Sinn Féin’s North America representative she was uniquely placed to help. Rita was quickly won over to the merits of the project and with her contacts in the USA, and especially within the trade union movement, she successfully reached out to nearly twenty different unions seeking their solidarity and their funding. LiUNA in particular, led by Terry O’Sullivan, and the Transport Workers Union, led by John Samuelson, have been especially supportive.

As a grateful acknowledgement of Rita’s singular contribution, and on the day I launched a Léargas book celebrating Rita’s activism, Terry O’Sullivan, former LiUNA president, and I, unveiled the plaque to Rita. Well done Rita.

Also on the same day I launched a Léargas – "An Bhean Dhearg: A Tribute to Rita O’Hare." It is available from www.sinnfeinbookshop.com and An Fhuiseog 55 Falls Road www.thelarkstore.ie

INTERNMENT AND MASS INCARCERATION

Wednesday August 9 was the anniversary of one of the most disastrous decisions in recent Irish history. On August 9, 1971 the Unionist Regime and British government introduced internment without trial. It was a watershed moment in the history of the northern state as hundreds were dragged from their homes, thousands of families were forced to flee to refugee camps, and many of those lifted in the early morning raids were beaten.

Internment was an act of mass political violence and intimidation. It had been used successfully in every previous decade since partition by the Unionist Regime. On this occasion it failed.

The use of internment and detention centres also followed a pattern employed by British governments going back at least to the middle of the 19th century.

Toady in African History:

— Bruce Mwale (@BruceMwale) December 31, 2022

In 1954, because of poor sanitation, typhoid breaks out at Manyani concentration camp built by Britain to imprison sympathisers of Kenya’s anti-colonial Mau Mau Rebellion. The disease kills 115 prisoners. pic.twitter.com/NzZMRwGTJL

Following the failed insurrection in India in 1857 over 20,000 people were incarcerated in what were called "mass encampments." The conditions were appalling. Forced labour and starvation were deliberately used to coerce those detained. Such camps were not just used for political prisoners. Later in the 1870s and 1890s, when plague and famine struck in India, new camps were established to separate the hungry and sick. Forced labour of the weak and sick was used again.

During the Boer War the British government ordered the construction of around 100 concentration camps into which more than 100,000 mainly women and children were herded. They died in their thousands through malnutrition, starvation and disease. In addition, 30,000 prisoners of war were transported to remote parts of the British Empire.

After the Easter Rising 1500 men were interned without trial. Most were held in the Frongoch internment camp in Wales. In the 1950s and 60s such camps were again put to use in Malaya and Kenya and other parts of the British Empire as native peoples fought for independence.

In her remarkable Pulitzer Prize-winning book "Imperial Reckoning," published in 2005, Caroline Elkins documented the systematic torture and brutality that took place in Britain’s detention camps in Kenya. She revealed a British strategy of detention, beatings, starvation, torture, forced hard labour, rape, and castration, designed to break the resistance of the Kikuyu people. More than a million men, women, and children were forced into barbed-wire village compounds and concentration camps.

Four years later, in 2009, five survivors of the Kenya detention system successfully sued the British government. The British have now changed the law here to prevent hundreds who were illegally interned in the 1970s from suing them.