Review of Albert Reynolds: Risktaker for Peace by Conor Lenihan (Merrion Press, £19.99)

Albert Reynolds was Taoiseach from February 1992 to December 1994. During that short period in office, in which he headed two uncomfortable coalitions, he played a major role in the Irish peace process. He was a co-signatory with Britain’s prime minister, John Major, of the 1993 Downing Street Declaration, which affirmed the right of the people in the Six Counties to determine their future. It stated that the United Kingdom would agree to the reunification of Ireland if a majority in the north favoured it.

This was a giant step forward at the time and, seen in retrospect, it was a transformative moment, putting politics at the forefront of the conflict: the force of argument would replace the force of arms. Of course, it took time. Five years was to pass before the Good Friday Agreement cemented in place the principle of consent. By then, Reynolds had left the Dáil. Yet his contribution to peace undoubtedly remains his greatest legacy.

What I could never understand was what moved Reynolds, who had never previously betrayed much, if any, interest in the north, to make it his foremost interest once he became Taoiseach. Supposedly, he did so because he thought the end to violence would prove good for business in both the north and south. It’s hard to buy that as his sole motivation, but Conor Lenihan, the author of this “first complete biography” of Reynolds, is unable to offer a better reason.

It is an example of the book’s overall failing. It does not begin to tell us what made Albert tick beyond his abiding love for business. Then again, perhaps that says it all. He saw everything through a commercial prism. He joined Fianna Fáil without a political background and without a political vision. But, having embraced the party, he certainly exhibited a great deal of political ambition.

The outline of his story is simple enough. Born in Roscommon, the youngest of four children, his father ran various small businesses, including a farm and a dancehall. His mother, a powerful influence in his younger years, was convinced he had academic ability and sent him off to boarding school, later expecting him to go into banking.

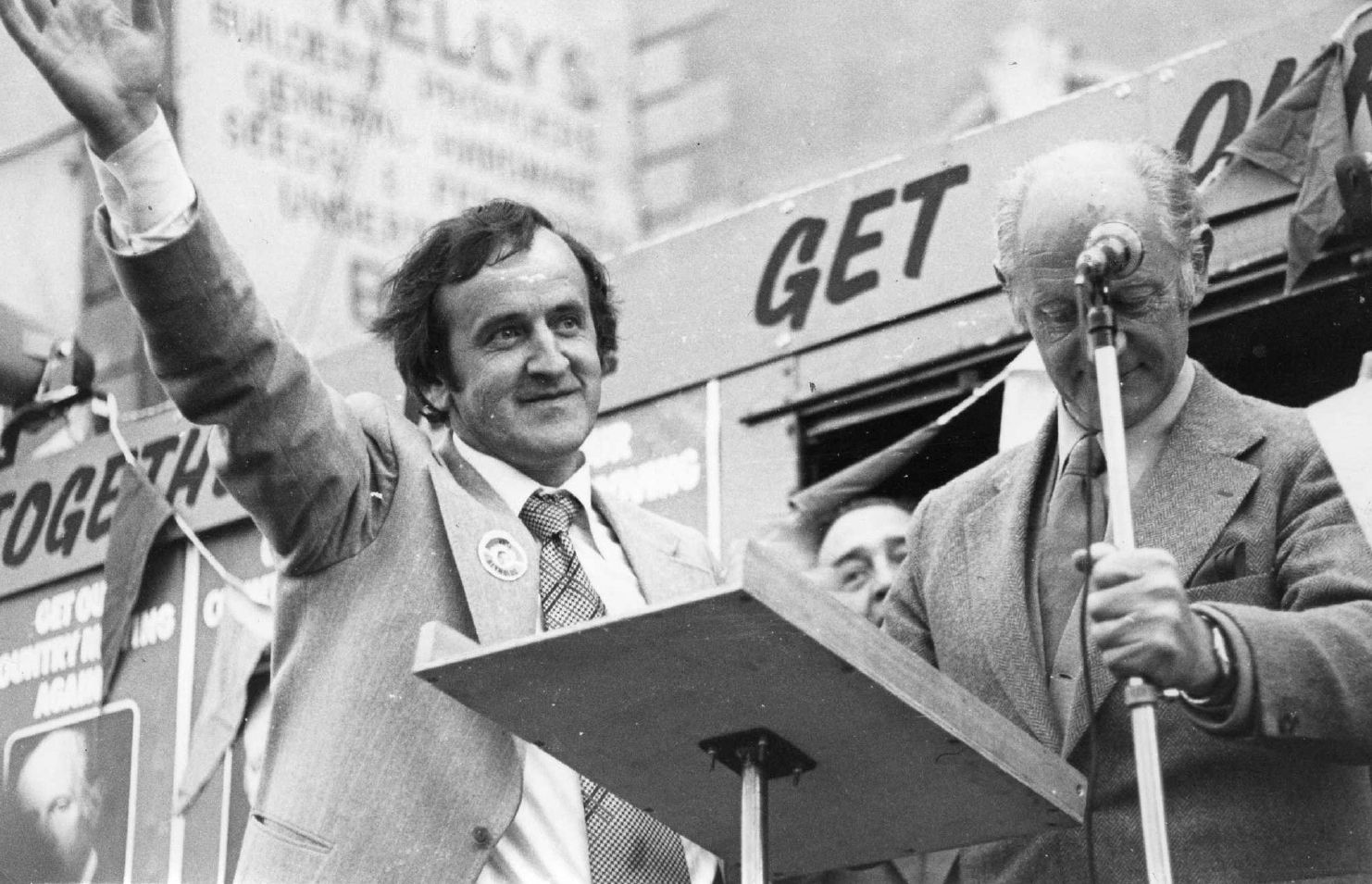

Outside Longford Courthouse, Albert Reynolds introduces Fianna Fáil leader Jack Lynch to a packed Main Street during the 1977 general election campaign. (© Derek Cobbe Collection)

Reynolds rebelled. He preferred to be his own boss. So, while marking time in a clerical job, he and an elder brother built up a lucrative dancehall business at a time, the early 1960s, when live music played by bands, and then groups, was hugely popular. Sadly, his partnership with his brother ended in a bitter legal dispute.

Soon after, spotting a gap in the market, he founded a company to produce petfood, which proved to be his most profitable venture. In order to do so, he had to secure loans from banks and state agencies, an early example of his negotiating skills.

By that time, he had moved into politics. His initial interest was spurred by his friendship with an independent Longford TD whose vote in the Dáil kept Fianna Fáil in government. That brought Reynolds into contact with the party’s electoral fixer and agriculture minister, Neil T Blaney. Reynolds watched from the sidelines in 1970 as Blaney was dismissed from the government, in company with Charlie Haughey, over allegations that they had plotted to send arms into the Six Counties to defend the beleaguered nationalist population.

In 1977, Reynolds was elected to the Dáil for Fianna Fáil and soon campaigned for Haughey to become party leader, and therefore Taoiseach, in place of Jack Lynch. Once that happened, he was a rewarded with a ministerial post. In the following dozen or so years, Reynolds headed five ministries and managed to embroil himself in a scandal about irregularities in the beef industry. Having distanced himself from Haughey, he then replaced him as leader in 1992.

To everyone’s surprise, Reynolds made peace-making in the north his priority. By far the most interesting passages in the book record in great detail his determination to overcome all the many reverses in order to bring about a negotiated settlement between the British governments and the IRA. The combination of his business acumen and down-to-earthness proved invaluable, as did his pragmatism, patience and prudent exercise of charm.

He made friends with Britain’s prime minister, John Major; he exploited his links with Unionists; he worked well with Father Alec Reid, who acted as the go-between with the IRA; and he nurtured key figures, including the Kennedy clan, in the United States. All of these relationships depended on trust. He had to trust them, and they had to trust him.

Reynolds was the right man in the right place at the right time. His initiative occurred against the background of the crucial talks between Gerry Adams and John Hume. The door to peace also swung wide open when Britain’s Northern Ireland minister, Peter Brooke, indicated that the British government no longer had a “selfish, strategic or economic interest” in the Six Counties.

Albert and Kathleen Reynolds relaxing with four of their seven children at Mount Carmel House, their Longford home. (© Derek Cobbe Collection)

Reynolds and Major evidently had to cope with “elements within the British intelligence services” seeking to destabilise moves towards a peace settlement. But they pulled it off. Indeed, so well did the two leaders get on that their negotiations survived bad-tempered rows. Lenihan, then a journalist, witnessed one of them. Sitting in Reynolds’s office he heard the Taoiseach “cursing and shouting” down the phone at Major. As Lenihan noted, Reynolds “had an ingenious way of turning up the temperature whenever he felt it necessary.”

Lenihan’s closeness to Reynolds is one of the book’s strengths and weaknesses. A former Fianna Fáil politician himself – as were his brother, father, grandfather and aunt – Lenihan cannot possibly be other than partial in his assessment of Reynolds and of the internal party squabbles in which his father was intimately involved.

Surely, he must also have been aware of contemporary political sensibilities by revealing that the current Fianna Fáil leader and Taoiseach, Micheál Martin, had the audacity to lend his support secretly to both Reynolds and his rival, Bertie Ahern, during their power struggle?

One aside also offered a striking insight into the casual corruption of Irish political life. When Reynolds was minister for posts and telegraphs he persuaded a telecom engineering company to site its £1 million headquarters in his Longford constituency. Pork barrel politics that, unfortunately, is all too common in the 26 Counties.

More amusingly, a bizarre anecdote that bears retelling involved Reynolds acting as a hostage negotiator when an Aer Lingus flight between Dublin and London was hijacked in 1981 by a monk whose single demand was that the Pope should reveal the so-called third secret of Fatima. Reynolds persuaded a newspaper to print a false story suggesting the Pope had complied. Result: end of hijacking.