Review of Donegal: The Irish Revolution, 1912-23 by Pauric Travers (Four Courts Press, £22.50/€24.95)

VISITORS who arrive in Donegal from countries elsewhere, including from Britain, wonder at the incongruity. It is Ireland’s northern-most county yet it is “in the South.” Surely it makes no geographical sense. Naturally, they ask why?

How come it wasn’t hived off with those other six counties that comprise 'Northern Ireland'? After all, it’s in Ulster, isn’t it?

Although I have answered that question many scores of times down the years, the simplicity of my reply rarely fails to elicit a measure of surprise, even shock. Perhaps it’s my bluntness: “Too many Catholics about the place.”

I particularly enjoy saying this to British people because so few of them know anything about their state’s closest colony. Home Rule bills, the Rising, the Tan War, partition, the civil war – not to mention, the hundreds of years of British rule that went before – are usually a revelation.

Irish history gets little, if any, airing in the British schools’ curriculum. When my visitors stand on the beach at Rathmullan and gaze at the statue representing the Flight of the Earls, they have no idea who sailed away and why.

They know nothing of the subsequent Plantation of Ulster, the confiscation of land on behalf of the Protestant settlers and the dispossession of the indigenous Catholic inhabitants. Therefore, they have no clue as to how that policy culminated in Ireland’s partition and, fifty years’ later, generated the conflict they know as 'the Troubles'.

Which takes us back to the reason for Donegal’s exclusion from the statelet. The problem for its architects, notably Edward Carson, was the preponderance of Catholics in Donegal. Its inclusion in 'Northern Ireland' would have threatened the overall Protestant majority.

It means that for overwhelming majority of Britons believe the people in the Six Counties are locked into an anachronistic battle between Catholics and Protestants. This, they find baffling because, as they inevitably go on to say, “we sorted that out centuries ago.”

So, devoid of context, lacking the essential knowledge of their own state’s instigation of religious strife for political ends, they hold fast to the misconception. Is there any greater example of the power of propaganda?

That is not to deny ongoing sectarianism, of course. What is concealed is the explanation for it, the cynical way in which the British state, in league with the planted people, ensured its continuance and volatility by creating an enclave based entirely on religious persuasion.

Which takes us back to the reason for Donegal’s exclusion from the statelet. The problem for its architects, notably Edward Carson, was the preponderance of Catholics in Donegal. Its inclusion in 'Northern Ireland' would have threatened the overall Protestant majority.

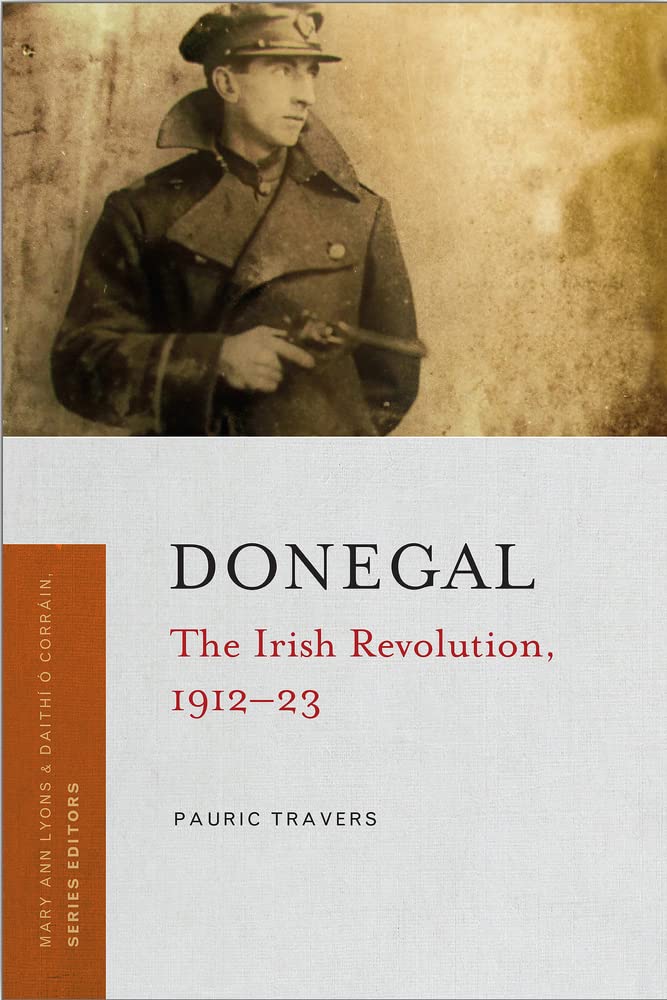

Eithne Coyle, Cumann na nBan organiser, at rifle practice in 1921

One of the values of Pauric Travers’s book about Donegal during the years of the Irish revolution is his recounting of Carson’s boastful lies to the county’s Protestant people. In 1913, at a meeting in Raphoe, Carson told Donegal unionists they would never be abandoned by their “friends and comrades.” At the time, he knew otherwise. The religious mathematics would destabilize his Protestant state for a Protestant people, as his chief lieutenant, James Craig, would later term it.

His duplicity was matched, nay exceeded, by that of prime minister David Lloyd George. He convinced the gullible leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, John Redmond, that the exclusion of the six counties would be temporary. Meanwhile, he assured Carson it would be permanent.

Lloyd George and Carson were far from the only story-tellers. Carson’s fervent supporter in Donegal, the fifth Earl of Leitrim – thankfully, the last of his name – had the gall to claim, without proof, that there was no enthusiasm among the county’s Catholics for Home Rule.

In fairness, as Travers records, Donegal had been anything but a hot-bed of revolutionary spirit before and after the Rising. It was partition, first as a proposal and then as a reality, that garnered impassioned nationalist opposition. One of the book’s fascinating passages concerns the way in which, during the civil war, Donegal’s pro and anti-treaty forces co-operated in cross border actions.

Travers, a native of Ballyshannon, has served his county well through his research. If he had a mind to, I think he could select one particular character from his account and write a compelling biography about her. For the exploits of Falcarragh-born Eithne Coyle deserve closer attention.

That unity quickly dissolved. In November 1922, eight anti-Treaty soldiers (the IRA) were arrested by Free State troops in Dunlewey, west Donegal, and tried by court martial for the possession of arms. They were all sentenced to death by firing squad and held, pending their execution, at Drumboe Castle in Stranorlar.

Over the following two months, there were protests by local politicians and calls for clemency. It was thought their sentences would be commuted until the killing of a Free State officer in Creeslough. That prompted the decision to execute four of the men – Charles Daly, Timothy O’Sullivan and Daniel Enright, all from Kerry, and Sean Larkin from Derry – on 14 March 1923.

They became known as the Drumboe martyrs and their deaths are regarded as a “massacre”. The tragic quartet are remembered each year with a well-attended march through Stranorlar, organised by Sinn Féin. Given that next year marks the centenary, a large turn-out is expected.

Travers does not mention these modern commemorations. He chooses to stick firmly to his historical brief, and there is much to appreciate in his detailed dissection of the shifting and conflicting loyalties of the various groups, unionist and nationalist, over the period.

It is always intriguing, however, to see the links between past and present. He tells how, in 1918, Patrick O’Mahony, full-time Sinn Féin organiser, stood trial with three comrades in Donegal Town on charges of drilling and unlawful assembly. All four refused to recognise the court, declined to give bail for good behaviour, sang the Soldier’s Song when sentenced to three months’ apiece, and then threatened to go on hunger strike if they were not treated as political prisoners. Now, where have we heard that before?

Travers, a native of Ballyshannon, has served his county well through his research. If he had a mind to, I think he could select one particular character from his account and write a compelling biography about her. For the exploits of Falcarragh-born Eithne Coyle deserve closer attention.

She was a leading light in Cumann na mBan from its inception. She set up a branch in Cloghaneely and soon encouraged her recruits to get involved in the campaign against conscription. Her husband-to-be, Bernard O’Donnell, also gave the women military training.

Coyle became proficient in the handling of guns, as a stunning picture of her, in oilskin trench coat, a man’s flat cap and toting a rifle during shooting practice, suggests. She took the anti-Treaty side and was eventually arrested, went on hunger strike, led protests against conditions in Mountjoy jail, escaped, was recaptured, and later succeeded Constance Markievicz as president of Cumann na mBan. There must be a book there, eh?