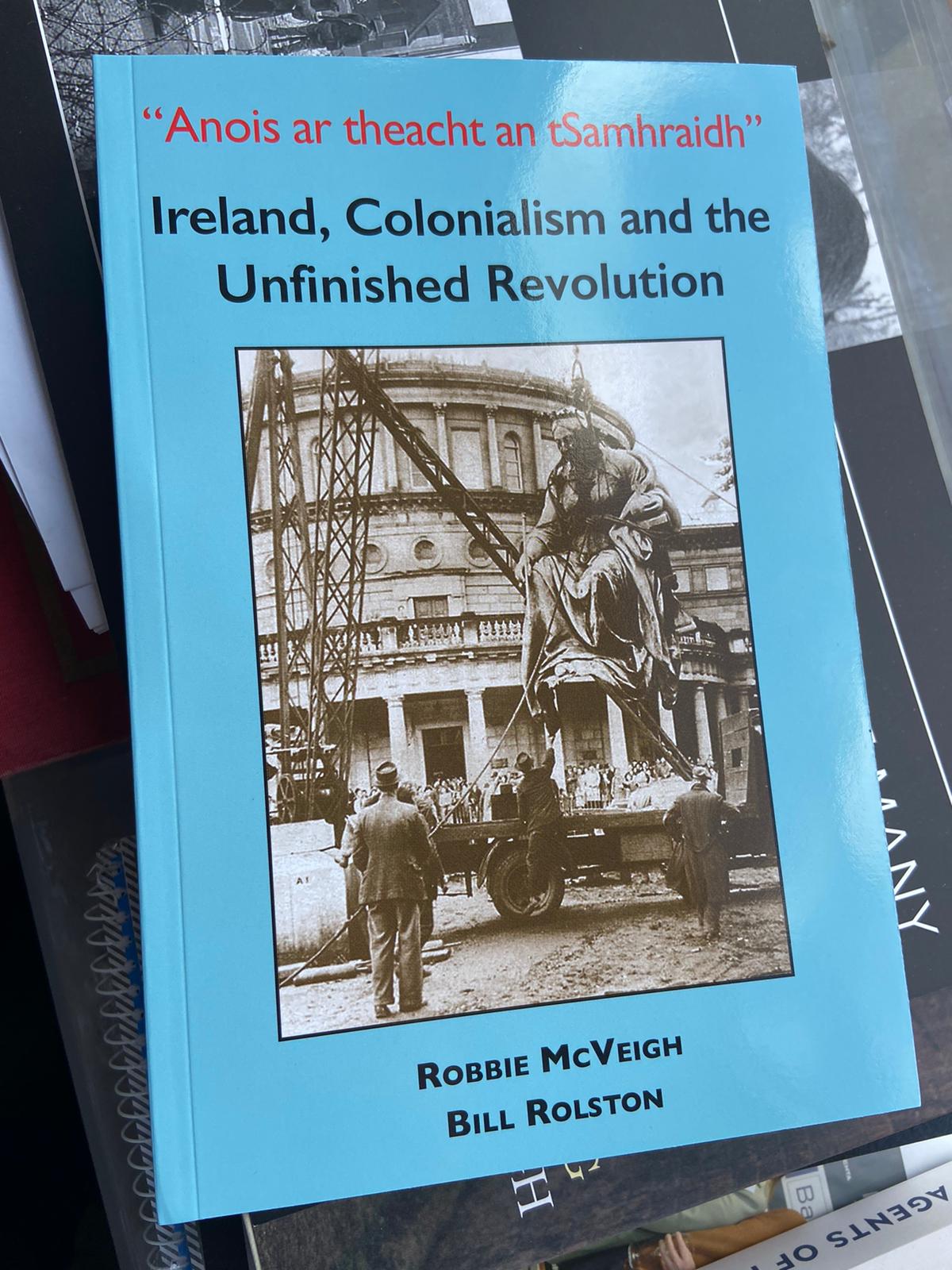

Anois ar theacht an tSamhraidh: Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution by Robbie McVeigh and Bill Rolston (Beyond the Pale Books, £19:95)

In order to civilise you, I must kill you. To make the killing worthwhile, I will expropriate your land and steal your resources. To make your life better, I will enslave you and demand you speak my language.

Should you reject my kindnesses, I must kill you again. And again. And again. This is the colonisers’ mantra, writ in blood down the ages from imperial Rome, on to imperial Spain and on to imperial Britain.

Here’s how the authors of this fascinating study put it: “Colonisation saw the destruction in whole or in part, of a chain of national, ethnic, racial and religious groups across the various European colonies.”

And how was this achieved? “Death by killing, death by disease, death by transportation, death by starvation, death through slave labour.”

By the prevailing standards of scholarship, Robbie McVeigh and Bill Rolston have produced what is likely to be described as a controversial book. Yet the real controversy is that it should be so regarded. For colonisation, as both concept and reality, holds the key to understanding the current state of the world. The legacy of colonisation remains as alienating today as it was at its inception.

Nowhere has this been more obvious than in England’s, and then Britain’s, subjugation of Ireland from the 12th century onwards. As soon as I mention that fact, I feel it necessary to point out that I am a Brit, raised in a country just after the second world war which was trying, and failing, to come to terms with its post-imperial past. At school in the 1950s, one wall of our classroom was devoted to a giant map of the world in which a vast swathe was coloured red, indicating all the countries colonised by Britain. We appeared to own the globe.

OMG! Britain is finally commemorating these British #CrimesAgainstHumanity.

— XallyWho (@XallyWho) June 6, 2021

- Jallianwala Bagh massacre in #India.

- Boer & black #African massacres in #SouthAfrica.

- Batang Kali Massacre in #Malaysia.

- Mau Mau Massacre in #Kenya.

- Opium war in #HongKong, #China.

- ... pic.twitter.com/A7cDXgB3ya

Although I did not realise it at the time, that map taught us children two lessons. First, our country was still the world’s leading nation (no matter that the map was hopelessly outdated). Second, the power of propaganda: through rose-tinted spectacles we were being imbued with the belief that our country, Great Britain, was indeed great. We were imbibing imperialist ideology.

BENEFICIENCE BESTOWED

The map dovetailed with the history we were taught about the beneficence we bestowed on all those countries we colonised. Where there was darkness we had brought light. Savages were tamed. The unwashed were cleansed. The uncivilised were educated.

It was not until I reached university that I came to understand British imperialism’s potency. It had sunk deep into the psyche of both our own population and the people in the countries our forebears had colonised. With, of course, very different outcomes, not least in terms of attitudes. In Britain, sadly, if inevitably, it proved to be a major cause of racism, which continues – witness the Brexit vote – to tarnish our society.

As for British racism against the Irish, it was manifested in the way we learned about Ireland as a troublesome, rebellious place ungrateful for Britain’s enlightening guidance. Hence the simian cartoons, those pathetic Irish jokes based on supposed stupidity, and related condescending nonsense about drunkenness and leprechauns.

These stereotypes were largely created in the 19th century as Ireland’s fightback against its coloniser began to take shape, only to be foiled by a mixture of British intransigence and political guile. The result, as the authors demonstrate in their detailed historic and political analysis, has been, to quote from their title, an unfinished revolution.

I found so much to appreciate in this book that I would need far too much newspaper space simply to reproduce my notes. What follows therefore is a mere glimpse at the contents. Firstly, to accept the centrality of the colonialist paradigm, it is necessary to acknowledge that Ireland was a conquered nation (and that a significant portion of it remains a colony). Historians who refuse to accept this reality would do well to reconsider the authors’ wholly convincing argument in which they chart the various stages of conquest and collaboration with the coloniser.

In truth, Ireland was taken by force of arms and held by force of arms. Its land was appropriated by Britain and settled by non-native people imported for the twin purposes of establishing economic superiority and quelling dissent. In response, its history has been punctuated by various attempts by the indigenous Irish to free themselves from the British yoke.

REVOLTS FRUSTRATED

These revolts were frustrated by the uninhibited exercise of British power in which ideological control proved as effective as military might as a constraining force. It meant that, at certain key points in Ireland’s history, when the emergence of an independent, democratic united nation appeared within its grasp, the wrong choices were made.

The coloniser was always pulling the strings and, mindful as I am about not wishing to denigrate those who played the role of British puppets, none of us should ignore the truth. Too often, at decisive moments, there was a fatal willingness to accommodate the empire rather than confront it.

Even better from Britain’s perspective was the decision of the 26-county state to cede far too much power to the Roman Catholic church. This ensured lasting hostility from its Protestant-dominated northern statelet.

Perhaps the greatest missed opportunity was the failure of the United Irishmen in 1798, a republican insurrection that linked Catholics and Protestants. Within three years, Ireland – unlike any other of Britain’s colonies – was incorporated into the United Kingdom. That decision helped to foster a prolonged wave of anti-British activity, but, as the authors stress, this did not take the form of an anti-colonialist campaign.

On this day in 1798 the United Irishmen suffered a heavy defeat at New Ross, Wexford. Cannon played a significant role, causing carnage amongst the massed ranks of rebels. Amazingly one of these guns still survives. Orginally from a ship, it bears the royal cypher of George III pic.twitter.com/qfMSa76weU

— Irish Archaeology (@irarchaeology) June 5, 2021

Although successive British governments railed against Daniel O’Connell, he was far less revolutionary than his Young Irelander critics, John Mitchel and James Fintan Lalor. I say that without wishing to deny O’Connell’s positive contributions. Similarly, and I admit this is one of history’s imponderable what-ifs, how unlucky for Ireland was it that James Connolly was executed and Éamon de Valera was not? And, yes, I recognise just how insulting that is to the Fianna Fáil faithful. So be it.

Arguably, no choice was as bad as that made in 1921. By accepting the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, its Irish negotiators sacrificed the republican ambitions outlined in the proclamation of the 1916 Easter Rising. The British engineered the retention of six Irish counties by taking advantage of the militancy of the people it had previously settled on the island.

LASTING HOSTILITY

Even better from Britain’s perspective was the decision of the 26-county state to cede far too much power to the Roman Catholic church. This ensured lasting hostility from its Protestant-dominated northern statelet. Well, not quite lasting because partition, being based on the existence of a Protestant majority, was bound to be vulnerable to demographic changes. Having been created on shaky foundations, it is now in the process of collapse.

In a sense, the coloniser realised this as long ago as 1993 when the then British prime minister, John Major, conceded that the British government did not have a “selfish strategic or economic interest” in Northern Ireland. But how could it extricate itself from a colony it no longer wanted?

Now, the militancy of the settled people was the problem rather than the solution, as remains the case today. Colonialism’s dependence on a strategy of divide-and-rule has come home to roost and Unionists find themselves unloved and unwanted by the nation to which they claim allegiance. Meanwhile, the two parties that have dominated governments in the 26-county state, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, are nervous of taking a decisive step towards reunifying the country.

CRITIQUING EMPIRE

It was left instead to the Irish president, Michael D Higgins, to raise the subject earlier this year in an Irish Times article which, in so many ways, echoes the authors’ thesis. “I am struck,” he wrote, “by a disinclination in both academic and journalistic accounts to critique empire and imperialism.” Quite so.

While McVeigh and Rolston agree on that, and do not shy from recording colonisation’s dire legacy, they remain optimistic about the future. Hence the title, Anois ar Theacht an tSamhraidh, Now the summer is coming. But is it? Who is preparing Unionists for a sunny life within a 32-county Irish republic?

Anois ar Theacht an tSamhraidh is available from all good book shops, at the Belfast Media Group offices at Hannahstown or from the Beyond the Pale website.