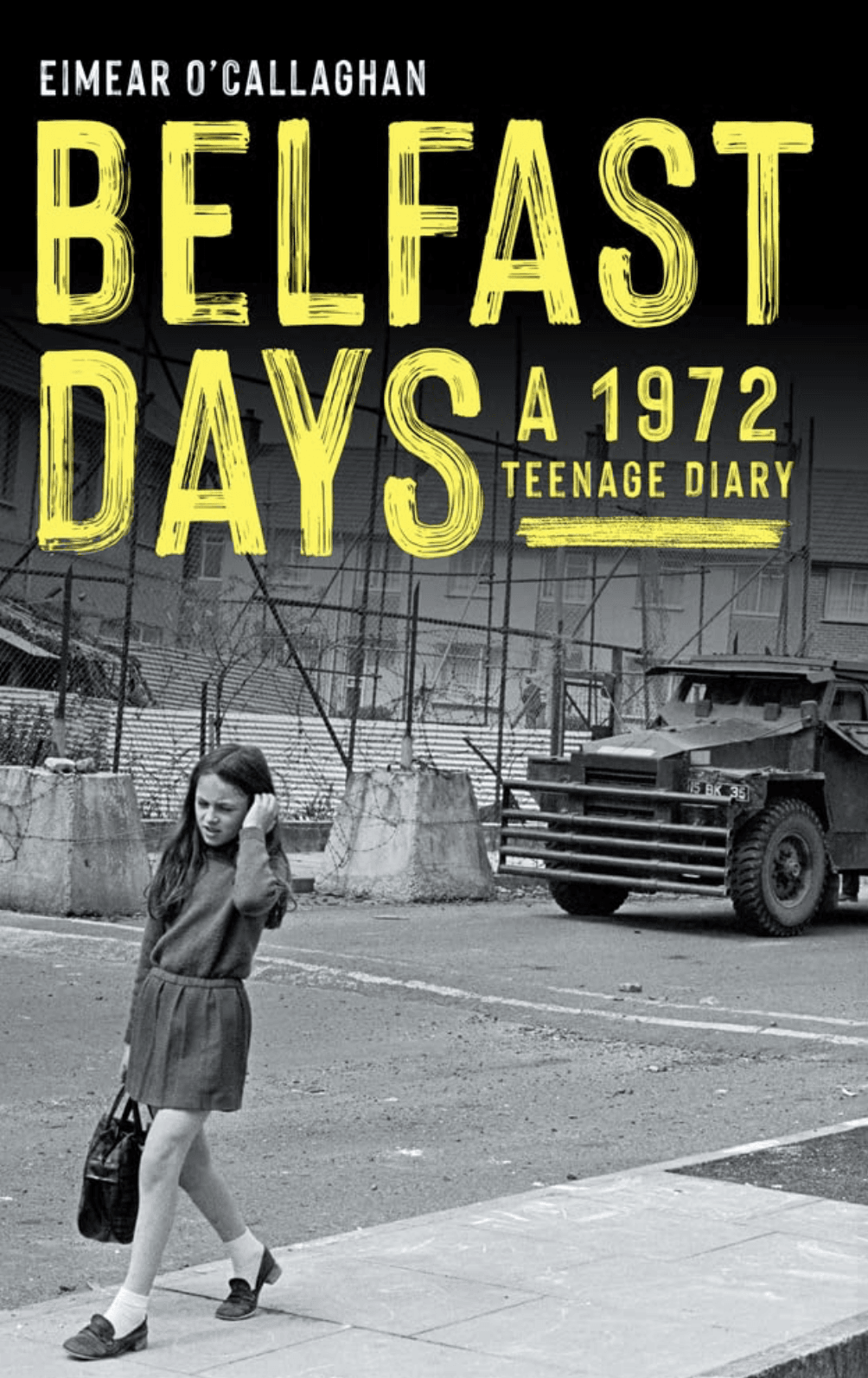

Belfast Days: A 1972 Teenage Diary by Eimear O’Callaghan, Merrion Press.

Reissued ten years after its publication, Belfast Days: A 1972 Teenage Diary, revisits the worst year of the conflict as seen through the eyes of 16-year-old West Belfast girl Eimear O’Callaghan.

Discovered nearly 40 years later, the honesty and savagery of the words shocked the former St Dominic’s pupil when she came upon the pages while clearing out a wardrobe. Eimear, who had gone on to have a career in broadcast journalism, was suddenly given a front row seat into her teenage self and the tumultuous events that were playing out within earshot and eyeshot of her Fruithill Park home.

“It teaches me that the passage of time may soften the stark images and dull the strident sounds of our violent history,” she writes in the prologue. “It can allow the ‘truth’ about the past to be distorted. My diary though, is unsparing. With its brutal candour, it has proved more trustworthy than memory.”

Paratroopers shot 28 people at it – 13 DEAD, including young boys. The army came on and told lie after lie, accused people of being bombers and gunmen.

Eimear discovered the diary on the eve of the publication of the Saville Report into the Bloody Sunday killings and here she was reading her own words into those events.

“I spent afternoon supposed to be studying but couldn’t settle. Big NI Civil Rights Association demonstration and march planned for Derry – hoped it would go off ok. However, in tears, we saw the 6 o’clock news. Paratroopers shot 28 people at it – 13 DEAD, including young boys. The army came on and told lie after lie, accused people of being bombers and gunmen. Terrible pictures on TV – army bending down to take aim at men and boys fleeing from shooting, shooting them dead in the backs. Italian reporter called them murderers. Father and son fleeing hands above head – both shot. Boy and girlfriend – shot girl, boy went to help her and they killed him.”

The diary reveals how the conflict impacted on the everyday education of young people in West Belfast in the 1970s. Schoolkids arriving late for their lessons due to riots or buses being burnt. Children walking long distances in all weathers to school only to be greeted by teachers who had no understanding of what they had gone through in the proceeding hours.

“Had a uniform inspection at 2 o’clock. Half the school look like tramps these days, wearing coloured coats over their uniforms for safety in mixed areas.”

Extracts from the diary are complemented by Eimear’s reflections on the events and the issues raised by her 16-year-old self. However, it is the immediacy of her original thoughts that bring home the hopes and frustrations of a teenage girl growing up in war-torn Belfast whose thoughts keep turning to pop music, boys and schoolwork but are dragged back with a thud to the latest killing.

Ah! Daddy is thrilled – walked in after work and announced he had ‘seen the glory of the Lord!’ Never thought he would live to see end of Faulkner and Unionism.

It's not unusual for a diary entry to end “Couple of more explosions down town” or “only one explosion tonight”; reminding you that the sound of distant, and not so distant, bombs was the soundtrack to early ’70s Belfast.

One interesting entry is the nationalist reaction to the proroguing of Stormont in March that year.

“We were allowed out of school early in anticipation of Protestants causing trouble – a lot of them had walked out of work – all feel betrayed by Mother England. Ah! Daddy is thrilled – walked in after work and announced he had ‘seen the glory of the Lord!’ Never thought he would live to see end of Faulkner and Unionism. We had a party in the house to celebrate, while two-thirds of the country is mourning, and one-third is rejoicing.”

Most of us would cringe at the very idea of being confronted by our teenage thoughts some forty years on. But Eimear O'Callaghan has done us a service by letting those words open a window into our collective past. They show that even as the turmoil and unjustness of war visits your own street, hope prevails during the darkest of times. Especially at the end of a teenager’s pen.