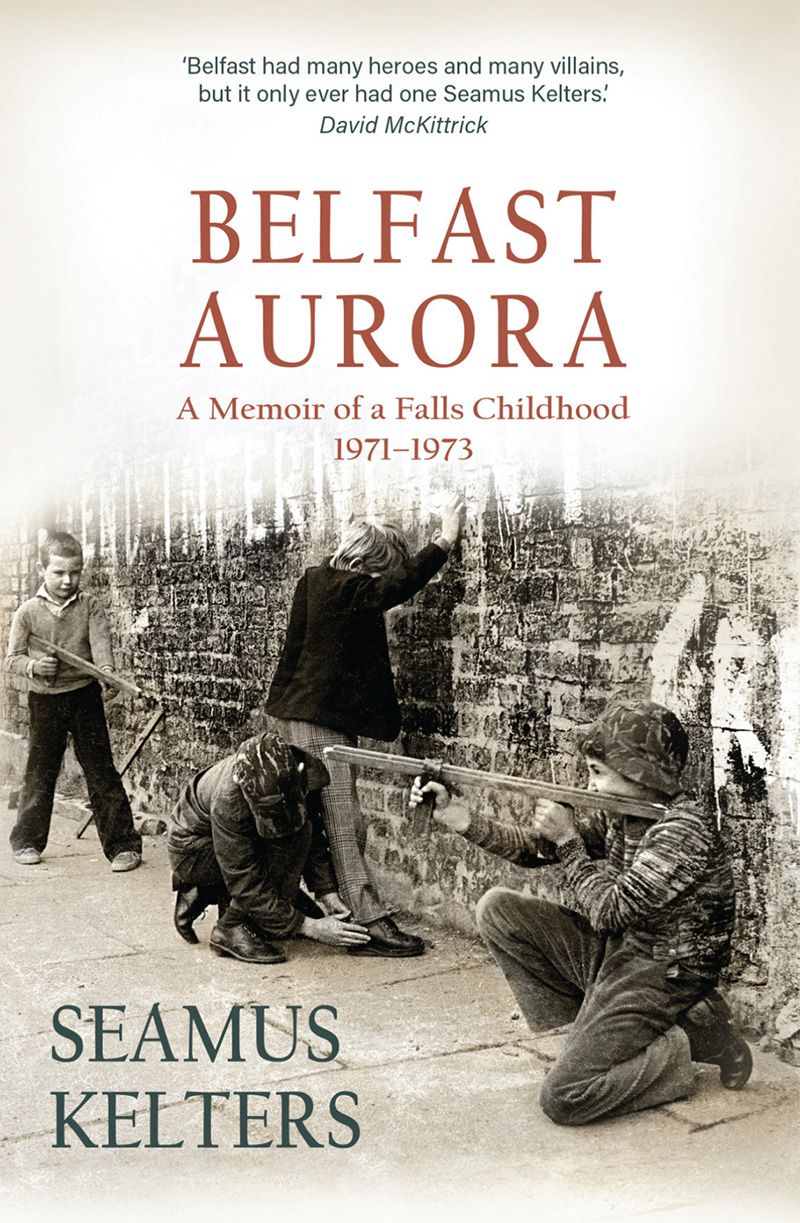

Belfast Aurora – A Memoir of a Falls Childhood 1971-1973 by Seamus Kelters (Merrion Press, £14.99)

BORN in 1962, Seamus Kelters would eventually become a journalist working for the Irish News and then the BBC. He is one of the authors of Lost Lives which catalogued the deaths of those who died during the conflict. He died in 2017 after a short battle with cancer at the age of 54.

Those short sentences in no way do justice to Seamus Kelters, however, they might in some small way give us a glimpse into the man who was born in the right place at the right time and who would tell the story of the Troubles from a child's perspective in this unique collection and who would give testimony to his family and the Falls community in which he lived in the midst of untold chaos and tragedy.

Each chapter can stand on its own as a short story. Reading through these 15 stories you get echoes and flashes of Michael McLaverty. It is only near the end of the book that Kelters tells us that Call My Brother Back is his favourite book.

I read it, disbelieving almost that someone would find the place where I was growing up worthy of story.

That was fifty years earlier where the same streets that Kelters was now walking every day on his way to school were once again suffering the plight of communal violence. These very streets were a window through which his grandparents gave up the visions and the ghosts of the past.

Seamus Kelters' grandfather was shot in 1921 and lived to tell the tale. His grandmother’s favourite uncle did not. She witnessed him being shot by ‘random fire’ outside her Lepper Street door as she went into the hall to greet him. The Troubles of the 1920s hang over these new stories as Kelters tries to make sense of the shootings and bombings that were a daily occurrence around him in early 1970s Falls.

There is his childhood memory of playing in the snow on the Whiterock Road one Sunday in January 1972 as his parents listened horrified to RTÉ radio at the rising death toll from Derry. The morning after Bloody Sunday his teacher handed the class coloured markers and paper and told them: “Draw what happened in Derry yesterday.”

The book opens with his parents buying a house in Springfield Park in the mid-1960s. Buying their first house was a big deal for his mother and father. However, tensions were rising in the city and from below Black Mountain “CS gas was drifting on the air along with distant yells”.

Kelters recalls the Ballymurphy Massacre when loyalists from Springmartin attacked Springfield Park. Internment had been introduced hours earlier. His family joined other Catholics fleeing across fields only to be met by the Paras. Four innocent civilians died that night.

There is his childhood memory of playing in the snow on the Whiterock Road one Sunday in January 1972 as his parents listened in disbelief to RTÉ radio at the rising death toll from Derry. The morning after Bloody Sunday his teacher handed the class coloured markers and paper and told them: “Draw what happened in Derry yesterday.”

Then there was the stone-throwing at British Army patrols – and the sense of victory at their withdrawal; the gun battles outside his granny’s Cavendish Street house and the panic and worry on Bloody Friday as he listened to the bombs going off, battling against the stream of people coming in the opposite direction up the Grosvenor Road, frantically searching for the “three dearest people in my life” – his mother, his father and granny.

And then after a disastrous visit to Butlins on a school trip where his class ended up fighting with a school from Drogheda, while one of his classmates killed a duck on the lake with one swipe of an oar, the admonished and disconsolate boys were soon headed home.

But this is a book punctuated with humour – and plenty of it. Accounts of bombings and shootings are juxtaposed with school stories. Their familiarity forcing me to laugh out loud on occasion.

A kid stood to read his ‘what my father does’ essay. He proclaimed: ‘My father has a machine-gun. He keeps it in the attic. He says it’s a Hoover but…’ That was as far as he got before a cuff on the ear from Mulvenna. ‘Don’t be telling those lies about your father; you’ll get him in trouble.’

And then after a disastrous school trip to Butlins where his class ended up fighting with a school from Drogheda, while one of his classmates killed a duck on the lake by dropping an oar on the unfortunate bird's head, the admonished and disconsolate boys were soon headed home.

We stopped briefly in Drogheda for the educational component to the day. We trooped into a church there and paraded in front of Blessed Oliver Plunkett’s head, behind glass, inside a gold casket. I looked at it in the same way I had watched the duck; part intrigued, part repulsed. The explanation muttered went along the lines of ‘the Brits did it’. We exchanged knowing looks, more subdued when we got back on the bus. It took the sight of soldiers at the border again to rouse us back into another refrain: ‘And every man will stand behind the men behind the wire’.

Listening to the rain on his window at night the ten-year-old noticed that there was rarely a shooting when it rained after dark. “I concluded that people with guns wanted to avoid getting them rusty.”

Recognisable characters fill the pages of this book and also the front room of Kelters' granny’s Cavendish Street home. Coming in for the latest news; crowding around the TV listening and commentating on the latest political debate. At one point a trout from a stream below Colin Mountain filled his uncle's new aquarium in the room too, only to be freed into the Waterworks.

But what never leaves Kelters and revisits him time and again throughout these stories is the memory of being ‘put out’ from his home in Springfield Park. On one occasion when he and his father returned to make sure the house was secure, a young couple were living there with a baby, having themselves been ‘put out’ from somewhere else in the city. They never returned to the house after that; at least not physically.

Belfast Aurora is ultimately a story of love and loss. It pervades these pages as heavy as the fumes from embers of distant fires and sometimes it manages to get into your eyes. Seamus Kelters left us far too early. He was a natural story-teller who had more stories to tell. We are much poorer for not having heard them.