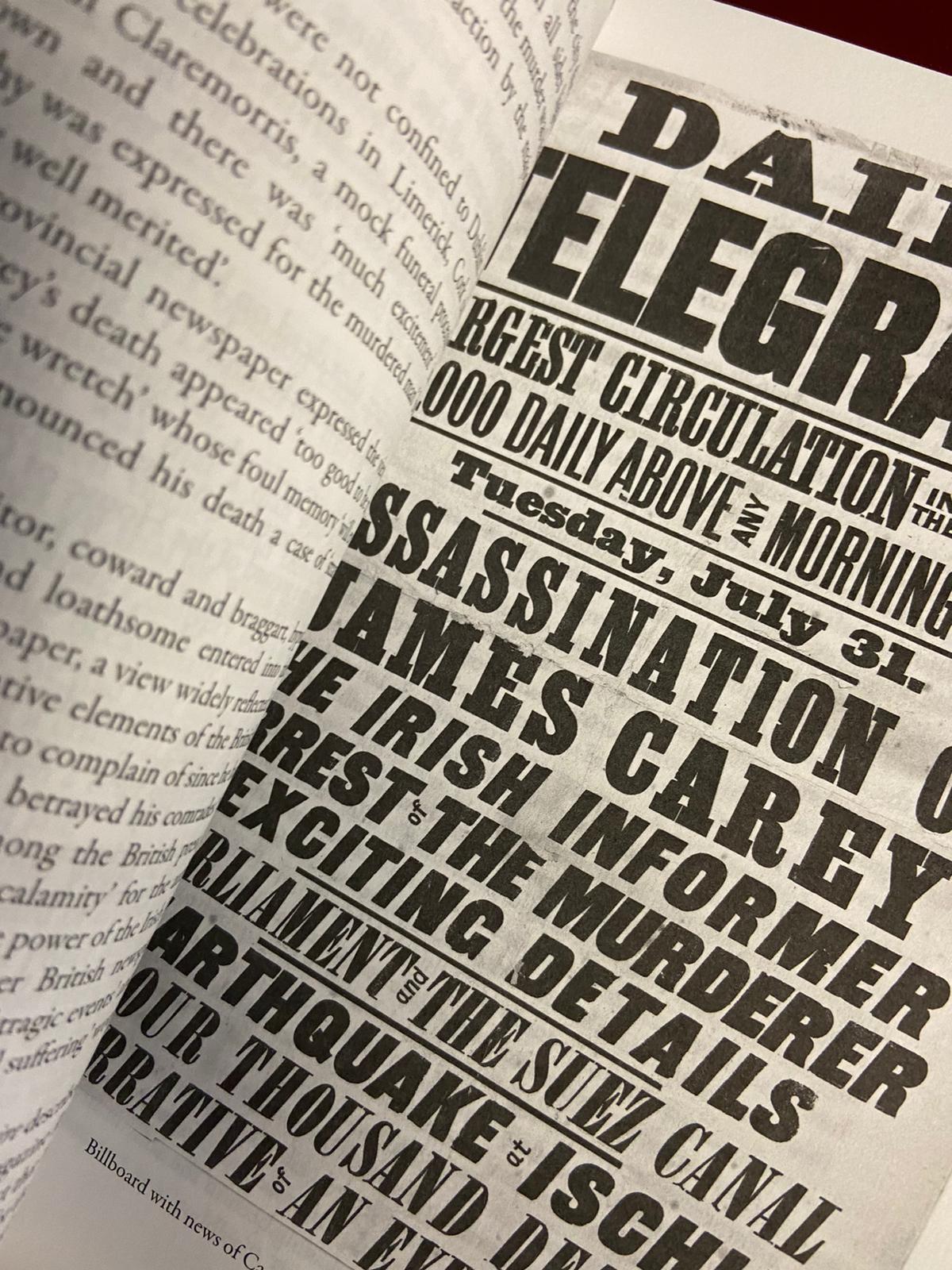

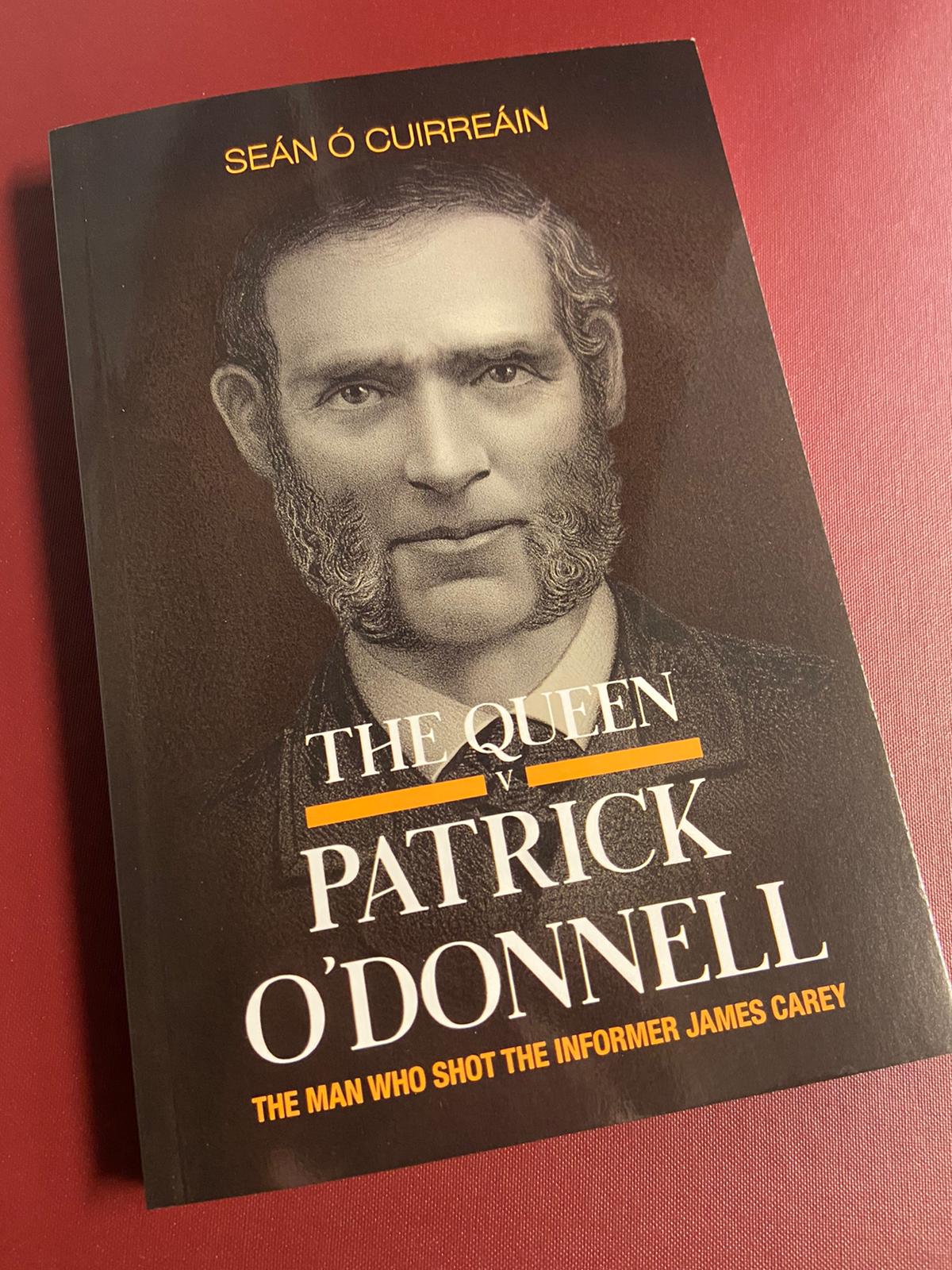

The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell: The Man Who Shot the Informer James Carey by Seán Ó Cuirreáin (Four Courts Press, £17.95) and The Irish Assassins: Conspiracy, Revenge and the Murders that Stunned an Empire by Julie Kavanagh (Grove Press, £18.99)

The assassinations of Lord Frederick Cavendish, chief secretary of Ireland, and Thomas Burke, the under-secretary, have been scrutinised many times by historians down the years.

The fatal attack in Phoenix Park in 1882 by the Invincibles, a radical splinter group of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), is regarded, at least by some, as one of the major reasons for the failure of the British parliament to grant Home Rule to Ireland.

Whether it played such a crucial role or not, it certainly upset Queen Victoria and convinced her prime minister, William Gladstone, that yet more repression was necessary in Ireland. But, as I say, there is little new to explore in both the details of the killings and their seismic political aftermath.

BACK DOOR INTO KILLING

How clever then that Seán Ó Cuirreáin has managed to open what might termed a back door into the affair. As is well known, five of the Invincibles were executed for the crime. Evidence against them was obtained by Police Superintendent John Mallon, who played off one against another to inform on each other.

His key informant was James Carey, a supposedly committed nationalist who – irony upon ironies – served for a while as a member of the IRB’s vigilance committee, which rooted out informers within the organisation. He played a leading part in the killings, helping to plan the attack as well as signalling to the squad who carried it out.

At O’Donnell’s trial in London, at the Old Bailey, Thomas Carey changed his story. This time, he told the court that O’Donnell had shouted: “I was sent to do it.” O’Donnell’s excellent defence lawyers challenged Thomas and forced him to concede that his memory was faulty.

Having turned Queen’s evidence, he appeared in court to give testimony against his former comrades, which ensured they had no hope of being acquitted. After they were hanged in Kilmainham prison Carey’s reward for his treachery was a new identity, an unconvincing disguise, tickets to travel with his wife and seven children to South Africa, and funds to create a new life in Durban.

Unsurprisingly, Carey was loathed by a large section of the Irish population, even by people originally outraged at the murders. For surely, there is no greater villain in Ireland than an informer. Yet it is a villainy which, odiously, runs like a thread through Irish history

On the journey to his new home, Carey – travelling under the name of James Power – was shot dead by an Irish man, Patrick O’Donnell, who was executed for the murder. He was fêted as a hero by Irish nationalists. Near his home place in the townland of Meenaclady, Gweedore, Co Donegal, a memorial was erected and songs, notably My name is Pat O’Donnell, were written and sung in his honour.

Historians have tended to relegate O’Donnell’s part in the story to little more than a postscript. But Ó Cuirreáin has elevated him to what amounts to a starring role (as does an excellent documentary drama, The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell, which was screened last week at the Galway Film Fleadh). After 138 years of myth-making, his research allows us to grasp the truth about O’Donnell’s life and death.

ILLITERATE LABOURER

He was an illiterate labourer, born in 1838 (although, all his life, he remained unaware of his birth year). In his childhood, his father sold the tenancy of his poverty-stricken farm in Meenaclady and used the money to take his family to America. He did well enough in his eight years there to raise enough to return to Gweedore, buy back his tenancy and open a public house.

In 1860, or thereabouts, O’Donnell also decided to chance his arm in America. He was reputed to have made, and lost, fortunes, but this was probably bunkum. He was, in fact, an iron puddler, a dangerous job which involved shovelling pig iron into a furnace to convert it into wrought iron. Only the toughest survived.

At no stage did O’Donnell appear to have had any political affiliations. Over the following 20 years, he went backwards and forwards between America and Ireland, plus a spell in Scotland. At some time, he married a woman in Philadelphia, Margaret McNulty, who had emigrated from a parish in Gortahork, neighbouring Gweedore.

In early 1883, he left her – without apparent acrimony – to realise his ambition to work in a South African diamond mine. He returned briefly to Ireland and spent time in Derry, where he met an 18-year-old Gweedore woman, Susan Gallagher, who was working in service. They travelled to London, where they failed to persuade a priest to marry them, agreeing to wed when they reached South Africa.

Over the course of the three-week voyage, where Susan pretended to be O’Donnell’s wife, they met James and Maggie “Power” and their children. The couples became friendly, and Power convinced O’Donnell that he should travel on to Durban. During the lay-over in Cape Town, an Englishman drew O’Donnell’s attention to newspaper sketches which showed that Power was Carey.

A VERY TROUBLED O'DONNELL

It was a very troubled O’Donnell who boarded ship, the Melrose, for the trip from Cape Town to Durban. He avoided Carey for a while, but the day after setting sail, he confronted him in the saloon, telling him he knew his real identity and calling him “the blasted Irish informer.” What is certain is that O’Donnell killed Carey with three shots. What is uncertain is exactly what happened before O’Donnell fired and the subsequent discovery of Carey’s gun in the pocket of his (Carey’s) 15-year-old son, Thomas.

O’Donnell maintained that Carey drew his gun and he had acted in self-defence. Thomas told a court in Port Elizabeth that O’Donnell had blurted out: “I didn’t do it.” Neither of the two crew members in the saloon heard the argument that preceded the shooting. Susan Gallagher, suffering at the time from sea-sickness, heard a “violent outburst of words”, but did not see what happened.

At O’Donnell’s trial in London, at the Old Bailey, Thomas Carey changed his story. This time, he told the court that O’Donnell had shouted: “I was sent to do it.” O’Donnell’s excellent defence lawyers – funded by donations from Irish Americans who viewed O’Donnell as a hero – challenged Thomas and forced him to concede that his memory was faulty.

With Thomas’s crucial evidence in dispute, it was perhaps unsurprising that the jury broke off from their deliberations to ask the judge a key question: what was the difference between murder and manslaughter? His explanation failed to satisfy them and they sent out from the jury room a further written question.

The discovery of that question by Ó Cuirreáin after it had been locked away in the British national archives for 138 years reveals that O’Donnell was the victim of a gross miscarriage of justice. The jurors asked: “If we find prisoner guilty of murder without malice aforethought can you take that verdict.”

But the judge did not answer the question, which clearly showed that the jury were eager to deliver a manslaughter verdict. He told the court the jurors had simply asked for a definition of malice aforethought. This was, to put it baldly, a lie. It went unchallenged by the defence because he did not reveal the full contents of the note in court. As for the judge’s reply to the jury, he blatantly guided them to a murder verdict, which they duly delivered.

THREE CHEERS FOR IRELAND

As he was removed from the dock, O’Donnell shouted: “Three cheers for Ireland… To hell with the bloody British government…” This outburst of patriotic pride accorded with the general belief that the assassin of an assassin was a Fenian. Hence his heroic status. But the reality was otherwise.

Today in 1882 British chief secretary of Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his under secretary, T.H. Burke are assassinated. Both are stabbed to death as they walk in Dublin's Phoenix Park by members of a nationalist secret society, the “Invincibles”. pic.twitter.com/ugjMZ7UFqI

— the painter flynn (@thepainterflynn) May 6, 2019

In her more conventional and hugely readable book, Julie Kavanagh also devotes a lot of space to O’Donnell and, like Ó Cuirreáin, she is entirely unconvinced about his being a political activist. Her interest was piqued by finding notebooks about O’Donnell left by her South African journalist father. Her main narrative, however, concerns Charles Stewart Parnell whose political ambitions were thwarted by the Phoenix Park murders and, of course, his adulterous love affair.

Both books are available from Four Courts Press or from An Ceathrú Póilí bookshop in An Chultúrlann,.

Grianghraf stairiúil den fhear Gaeltachta a mharaigh ceannaire na Invincibles aimsithe tar éis 138 bliain https://t.co/zXgzCQdR27 pic.twitter.com/pjIWI5Gk1d

— Tuairisc (@tuairiscnuacht) July 16, 2021