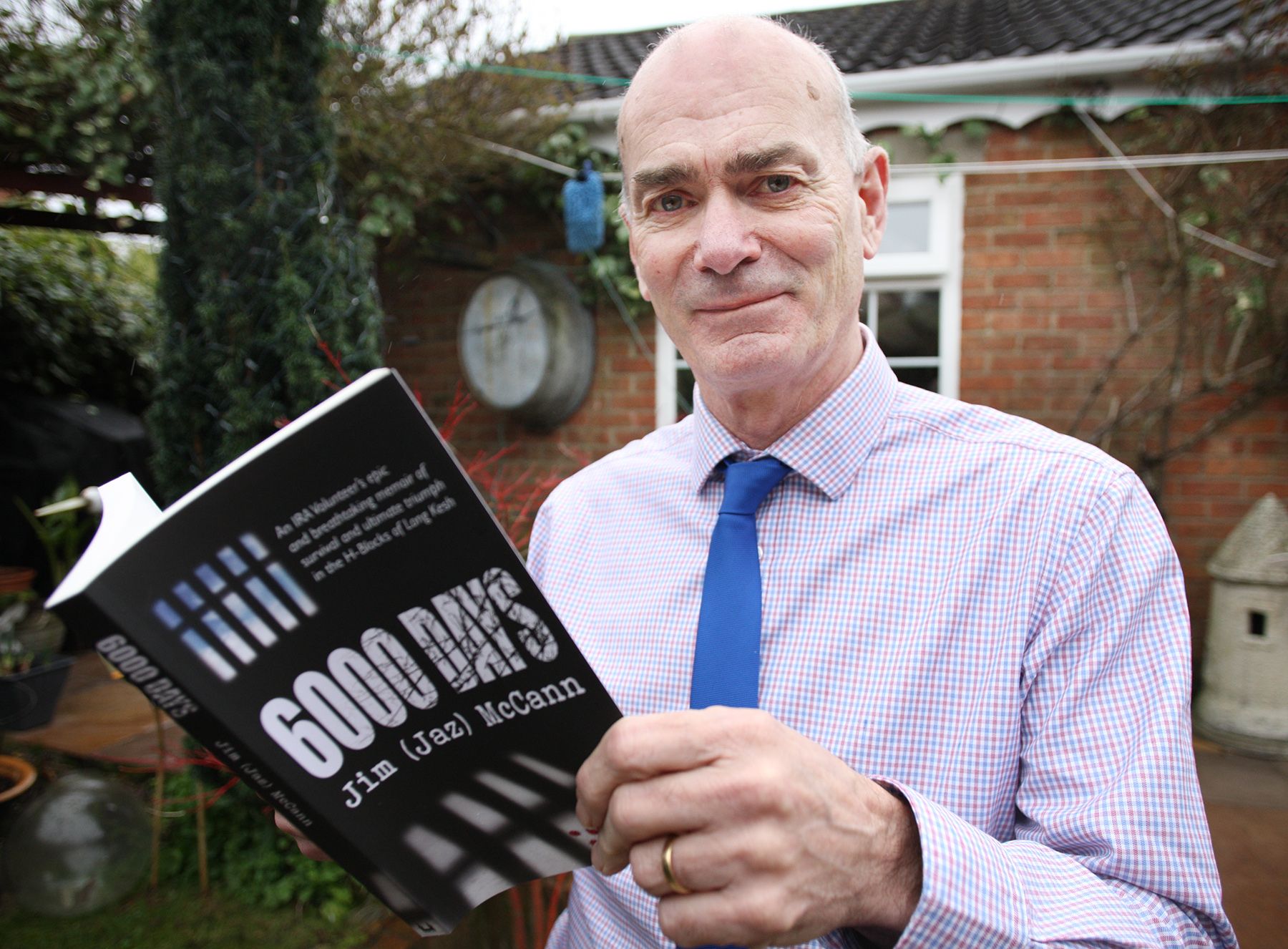

6000 Days by Jim (Jaz) McCann. (Elsinor Verlag, 2021.)

IN the concluding part of this book, Jim McCann celebrates the birth of his first child by writing: “I had overcome imprisonment... not only was I going to share it with my loved ones. It was fulfilment, it was ecstasy.”

After the previous 250 pages, in which he recorded his trials and tribulations as a prisoner in the H-blocks, we, the readers, are with him. We can understand his euphoria. We not only admire the fact that he survived 6,424 days in jail but that he managed to do so in such appalling conditions.

But it is the next sentence that makes this prison memoir so exceptional. “There had been special moments like Bobby [Sands]’s election, the escape, that first Christmas parole, but this capped them all.” This linking of his intimate domestic concerns and the wider struggle encapsulates McCann’s overall theme: republicanism unites the personal and the political.

Aged 20, McCann was sentenced to 25 years by a Diplock Court (no jury, one judge) for attempting to kill an RUC officer. He would go on to serve 17 years. At every stage of his imprisonment, through the blanket protest, the dirty protest and all the resulting brutal beatings and casual punishments, he was sustained by the fact that his refusal to bend had a political purpose.

That he did so while fearing the inevitable violence that would be meted out to him made his stand all the more courageous. Not that the modest, phlegmatic McCann even hints at his defiance in terms of his own bravery. Instead, he reserves such praise for Sands and his nine comrades who died while on hunger strike, especially Joe McDonnell. It was a uniquely sobering moment for McCann.

He writes: “Bobby’s death, and Joe following him on the stailc [strike] was a turning point in my life. I had been convinced that justice always prevails and those that fight for what is right always win through... Now reality was hitting me... being right did not necessarily equate with gaining justice.”

Bobby’s death, and Joe following him on the stailc [strike] was a turning point in my life. I had been convinced that justice always prevails and those that fight for what is right always win through... Now reality was hitting me... being right did not necessarily equate with gaining justice.”

His admiration for the “fearless” McDonnell’s “heroic qualities” shine through his account of the routine brutality suffered by all those who refused to wear prison uniform. McCann quotes a screw who thought McDonnell “the toughest prisoner he had ever come across” and tells of his friend’s way of lifting morale after savage beatings by prison officers. He would rally his bloodied and bruised comrades by telling them: “There’s going to be bad days for these good ones.”

McDonnell, known for his banter and dark humour, was the fifth hunger striker to die. McCann calls it a privilege to have shared jail time with “this giant of a man”, commending “his selflessness and dedication to a cause he would never allow to be criminalised.”

Although the passages on the hunger strikes are, unsurprisingly, the most difficult to read, there is a virtue in the way McCann describes them. His straightforward prose, factual and devoid of adjectives, adds to the poignancy of those tragic events.

Some of McCann’s memories appeared in a previous book, Nor Meekly Serve My Time, but this fuller, detailed version offers a much deeper understanding of what it was like to spend year after year undergoing a succession of attempts by officials to humiliate prisoners in order to break their resolve.

Optimism breeds moments when everything looks as if it will turn out well. In the summer of 1978, for instance, the men “were on a high” in the belief that the prison administration was “on the back foot” and “it would only be a matter of time before political status was conceded.”

With hopes dashed, the men rely instead on raising their spirits by securing small victories against the prison regime. They smuggle tobacco; they maintain communications with the IRA leadership; they even get hold of a radio. One particular victory had wider ramifications: the election success of Bobby Sands. As McCann acknowledges, although it wasn’t clear at the time, it was to set the republican movement on a path towards a new strategy.

That was to prove, as we know, a slow process. Inside the Maze, in the aftermath of the hunger strike, there was a determination to take the initiative, to land a propaganda coup against the authorities. The result was the 1983 mass escape from a prison regarded as escape-proof.

Once again, it is the very down-to-earth nature of McCann’s account of his part in the chaotic enterprise that is so compelling. He conveys the tension by highlighting his personal dilemma. Should he have left the trolley in the canteen as instructed? Did he misunderstand those instructions? Was he going to be responsible for the failure of the escape?

Once again, it is the very down-to-earth nature of McCann’s account of his part in the chaotic enterprise that is so compelling. He conveys the tension by highlighting his personal dilemma. Should he have left the trolley in the canteen as instructed? Did he misunderstand those instructions? Was he going to be responsible for the failure of the escape?

With that drama behind him – and, no, he did not misunderstand – comes the main event: the attempt to squeeze a car between closing gates. Then he makes his break on foot, running past watchtowers manned by soldiers uncertain whether to shoot at the fleeing prisoners. McCann’s freedom was short-lived because he was quickly recaptured, but the exhilaration at having taken part helped him survive the beating by guards on his return. “The screws were like a pack of wild dogs,” he recalls.

He never lingers for long on descriptions of these terrible moments, preferring to point to the camaraderie among his fellow inmates and also to remember instances of wit. With married men being allowed to take visits, one man argued that because he was engaged, and therefore “nearly married”, he should have a similar deal. McCann’s friend, JT, replied he should “nearly take a visit.”

But it is wisdom, rather than wit, that informs the central message of this book: the power of the state can be defeated by people who put principled politics above personal gain. The sacrifice of the hunger strikers, concludes McCann, had not been in vain.

As for McCann, he graduated with an Open University degree while in jail. After his release, he went to Galway University, gained a master’s degree in education, qualified as teacher and is now vice-principal of a West Belfast school. And, yes, he remains a republican. His is a truly noble story.