LAST week marked 50 years since the death of Frank Stagg on hunger strike in Wakefield Prison in England. Events, including a black flag vigil and a march and rally, were organised to remember the Mayo man. Gerry Kelly, who was on hunger strike in England in the 1970s for over 206 days, during which he was force-fed 167 times, gave the main oration in Ballina and spoke of Frank’s great courage and commitment.

I was in Long Kesh when Frank died on February 12, 1976, after 62 days on hunger strike. Britain’s intransigence and in particular the obduracy of the then Home Secretary Roy Jenkins ensured that Frank’s fourth hunger strike would result in his death. As we walked around the cage or sat in our cells the talk from when Frank embarked on his fast was about his resolve and strength of character as on his own he faced the brutality of a British system determined to break him.

Two years earlier we had watched as Frank’s friend and comrade Michael Gaughan, another Mayo man, had died on hunger strike.

Although our conditions of imprisonment in Ireland were much different from those being held in the solitary and hostile atmosphere of English prisons, nonetheless there was a connection between us. We were political prisoners who in our own way and our own time had battled against the conditions under which we were held. We could identify with and understand the motivation and impulse of Michael and Frank, and others in Parkhurst and Albany and other English prisons, refusing to accept criminalisation.

Within the cages in Long Kesh there was a deep sense of sadness when the news of his death broke that Thursday. The image of a fragile, weakened Frank dying alone in Wakefield prison touched all of us.

That sadness turned to anger and outrage when the Irish government hijacked Frank’s body as it returned to Ireland. His remains were kept from his family as it was flown to Ballina by helicopter and buried in an unmarked grave. Frank had wanted to be buried next to Michael Gaughan. But the Fine Gael government chose instead to exclude the family. They buried him in an unmarked grave, poured concrete over his coffin and placed a 24-hour guard on the grave.

Frank’s brother George later described how, when he took his mother to visit the grave, Special Branch officers took photographs of her.

George later discovered from Jane Ginty, who worked in the cemetery, that no-one had bought the grave they had placed Frank in, so he bought it and the one next to it. For a year the Gardaí stood watch but by the following summer they pulled the guard off. George and five others, waited until November 5, 1977, and then began the challenging task of removing Frank’s coffin.

They carefully carried the coffin on a sheet of plywood, fearful it might break as they moved it to the Republican Plot. There George and his comrades buried Frank Stagg beside Michael Gaughan. They saluted both volunteers and returned to their homes. George had fulfilled a great sense of personal duty to his brother. As he headed home he recalled his words to the Garda superintendent at Shannon airport when Frank’s coffin was stolen. He said: “I’m telling you now, I promise you. A day will come and I’ll have him back.”

George was true to his word.

Holy smoke! I’m so glad my puffing days are over

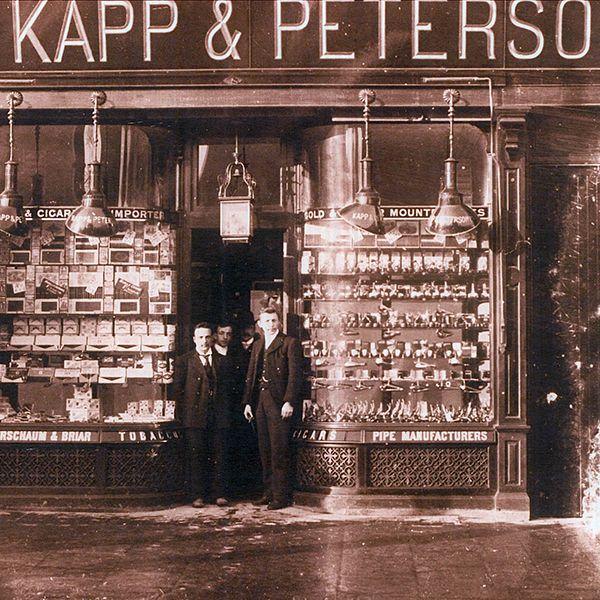

I USED to smoke. I was very addicted to it. I smoked everything that was legal. I smoked a pipe for years. I liked the pipe. There is a certain ritual attached to pipe smoking. Filling your pipe requires special skills. It takes time. And care. Fill it too loosely and it will not last long. Too tightly and it will not burn at all. Most pipe smokers had a number of pipes. But there was always a favourite one. My favourites were invariably Kapp & Peterson. Particularly the bendy ones, favoured by Sherlock Holmes. Kapp and Peterson still have a shop in Dublin, a shop which got an honourable mention in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot. In Belfast Miss Moran’s in Church Lane, which is still doing business, was a favoured supplier of pipes and good tobacco.

TRADITION: The Kapp & Peterson shop is still in Nassau Street

Pipe tobacco is of course a matter of choice and taste. And addiction. I was inclined towards heavier brands like Condor. The I graduated to War Horse, particularly War Horse plug tobacco. The preparation of this type of pipe filler requires a pen knife for cutting off little slices of tobacco. These were then rubbed between your hands until they were reduced to the desired consistency. This added to the ritual. It was probably therapeutic, if that’s not a contradiction. Ditto with the smell of pipe smoke. Back in the day pipe smokers were a fixed presence in pubs and at most social gatherings. Many people, barely visible in the clouds of smoke, would declare how much they liked the smell. Nowadays a pipe smoker is a rarity. So too are clay pipes. It was common to find old clay pipes, usually white with broken stems, in old houses or outhouses. Duidíní. Woman as well as men smoked them. They also used snuff. But that’s another story.

I smoked cigars and cigarettes as well, including roll-ups. I even had one of those little contraptions that allowed you to put the cigarette papers into a little roller filled with loose tobacco, and after a wee twiddle out popped a feg. In those days before the advent of tipped cigarettes I mostly smoked Gallaher’s Blues, Senior Service, Park Drive or Woodbine. Some shops sold single cigarettes. And packets of five. That’s what sparked this recollection. I found an empty five packet of Wild Woodbine in a drawer at home.

Looking back on it, it was sheer madness to suck smoke into our lungs. But we did. Or many of us did. Maybe most of us. Even people who didn’t smoke inhaled the clouds of smoke which filled every room where people gathered. At home or in social gatherings outside the home. When I was a curate in the Duke of York pub we used to regularly wash down the paint work and mirrors. The water soon turned brown as the nicotine washed off. Soon our buckets of water were coffee coloured. Somebody always said, “I wonder what our lungs are like.” But it made no difference. We puffed away.

Then came the years of enlightenment. Children in particular were educated in school about the health risks of smoking. It made little difference to the big tobacco companies. They continued their saturation advertisement campaigning. Our Gearóid played a big role in persuading Colette and me about the dangers of smoking. He was at Saint Finian’s Primary School at the time and a diligent teacher, and his own common sense made him an anti-smoking advocate. So first we were persuaded not to smoke at home. I was trying to stop by this time. But it wasn’t easy. I did it so often I got quite good at stopping. Once Gearóid caught me smoking in the toilet after I told him I had stopped. He was so let down I never smoked again. It was one of the best things I ever did.

Go raibh maith agat, a Ghearóid.

Nora Comiskey: Activist and patriot

IT was with sadness that I heard of the death last week of Nora Comiskey. Many Dublin republicans and some of us from Belfast and other parts knew Nora over many years. She was a former president and long-time activist in the 1916-1921 Club. This was a unique institution founded in the 1940s whose aim was to try and bring together some of those who fought on the pro- and anti-Treaty sides in the Civil War.

RIP: Nora Comiskey

Many did, including Nora who had been in Fianna Fáil. Its founding charter is the 1916 Proclamation and among its objectives are a commitment to honour those who fought for Irish freedom and who work for its achievement. It also seeks to contribute to the cause of an Ireland – united, independent and sovereign.

In 1989 a group of well-known activists including Nora, artist Bobby Ballagh, trade union leader Matt Merrigan, Fr Des Wilson, and others established the Irish National Caucus. Its aim was a united Ireland and to that end it held public meetings, lobbied the Irish government and organised for the 75th anniversary of the Easter Rising. In later years Nora was a supporter of the efforts to protect the Moore Street 1916 Battlefield site from the developer’s plans to demolish much of it. She was a sound republican and a patriot.

Nora will be sadly missed. Especially by her children. I extend my condolences to them, to Joe, Susan, Dervala, and Sinead, her grandchildren and her wider family circle.