Unionism, especially its DUP component, has been talking up unionist and loyalist resistance to the Irish Protocol since before Boris Johnson dirty-Joed them, broke his commitments to them, negotiated and then signed up to the Protocol.

There is some evidence of this in the loyalist street disturbances earlier this year and the sacking of Arlene Foster and of Edwin Poots. The dramatic decline in the polling fortunes of the DUP, as it flounders about trying to assert its former role as the undisputed leader of unionism, is also linked to its stance on Brexit and its transparent efforts to blame everyone else for a debacle they helped create.

Jeffrey Donaldson was in Dublin two weeks ago meeting An Taoiseach Micheál Martin. The Protocol was top of his agenda. The arrogance and rhetoric were loud – the politics insipid. He was at it again last week when he met the Tánaiste in Belfast. “The Protocol, the Irish Sea border, has to go,” he told Leo Varadkar.

If unionism doesn’t get its way then the Protocol, he said, “has the capacity to so undermine the political progress here that it drags us backwards... the Irish Government needs to very quickly recognise the damage that this protocol is doing to political stability in Northern Ireland.”

The DUP leader speaks as if he represents the majority of citizens in the North. He doesn’t. The political instability he speaks of is rooted in the attitude and behaviour of the DUP he now leads. Donaldson refuses to accept the reality that he represents a minority. He seems to believe that if he says something often enough – however inaccurate or plain wrong – that people will believe it. Even Jeffrey himself doesn’t. So, the Protocol is all Dublin’s fault. The Protocol is damaging the Northern economy. The business and farming sector are opposed to it. It is undermining the Good Friday Agreement. And so on. None of which is true.

Brexit is the responsibility of those who advocated for it, campaigned for it and voted for it, especially the DUP.

The fact is, a majority of citizens in the North voted against Brexit. They wanted to remain within the EU. They were worried by the likely economic dislocation Brexit would bring. And they were right to be worried. Its impact on the British economy is clear for all to see. Ian King, who presents the daily business programme on Sky, summarised the situation for many last week, when he said: “England has become a country where the pubs have no beer, farmers don’t have anyone to pick their fruit and even if they did there aren’t enough lorry drivers to get it to the shops.”

The medical supplier Seqirus has said it is postponing deliveries due to a Brexit-related shortage of lorry drivers. Logistics UK, which represents freight firms, and the British Retail Consortium (BRC) warned last month that the loss of 25,000 EU drivers is putting significant pressure on supply chains for retailers. The list of companies impacted is growing daily – Brewers, Coca Cola, Nando’s, McDonald’s, BP and Iceland are just some. The Bank of England has also reported shortages of furniture, car parts and electoral goods, as well as cement and timber for the construction industry.

In stark contrast, the most recent trade figures for the island of Ireland reveal that the business sector is taking advantage of the unique position of the North which is in both the EU single market and the customs territory with Britain. Last month the Central Statistics Office (CSO) in Dublin released trade figures showing what the London Guardian has described as evidence “deeper economic unity on the island of Ireland”.

The value of goods moving North to South in the first six months of 2021 dramatically increased by 77 per cent to €1.77 billion (£1.5 billion) – an increase on the same period last year when it was just under €1 billion. The value of goods travelling South to North also jumped by 40 per cent to €1.57 billion. This is an increase of almost half a billion over the same period last year. The Guardian newspaper concluded: “If it is sustained, Northern Ireland’s deepening economic ties with the Republic – and weaker ones with mainland Britain – will raise questions over the region’s relationship with the rest of the UK.”

So, where now stands loyalist/unionist resistance to the Protocol? Two weeks ago Jamie Bryson and Jim Allister and an assortment of hangers-on travelled to Enniskillen to campaign against the Protocol. The reports on the numbers who attended vary. Most fall between one hundred and three hundred.

One seasoned journalist from Fermanagh, Denzil McDaniels, writing about the Enniskillen protest said: “It’s clear that decisions to accommodate Brexit are taken at an international level and if there has been a betrayal of Unionism, loyalists should remember that it was their own basketcase of a British Government that let them down. That should be the real focus of their disillusion. Not the Irish Government and certainly not the people of Fermanagh who don’t want a return to the difficult times of Borders past...”

And that’s the prize we have to keep our eyes firmly fixed on. No going back. No returning to the past. A future in which we can all live in harmony and equality with each other. I believe that can be best achieved in a United Ireland. Others have a different view. Okay. Let’s talk about it. Are you listening, Jeffrey?

Pamphlets bring to life the vibrant history of our city’s tumultous past

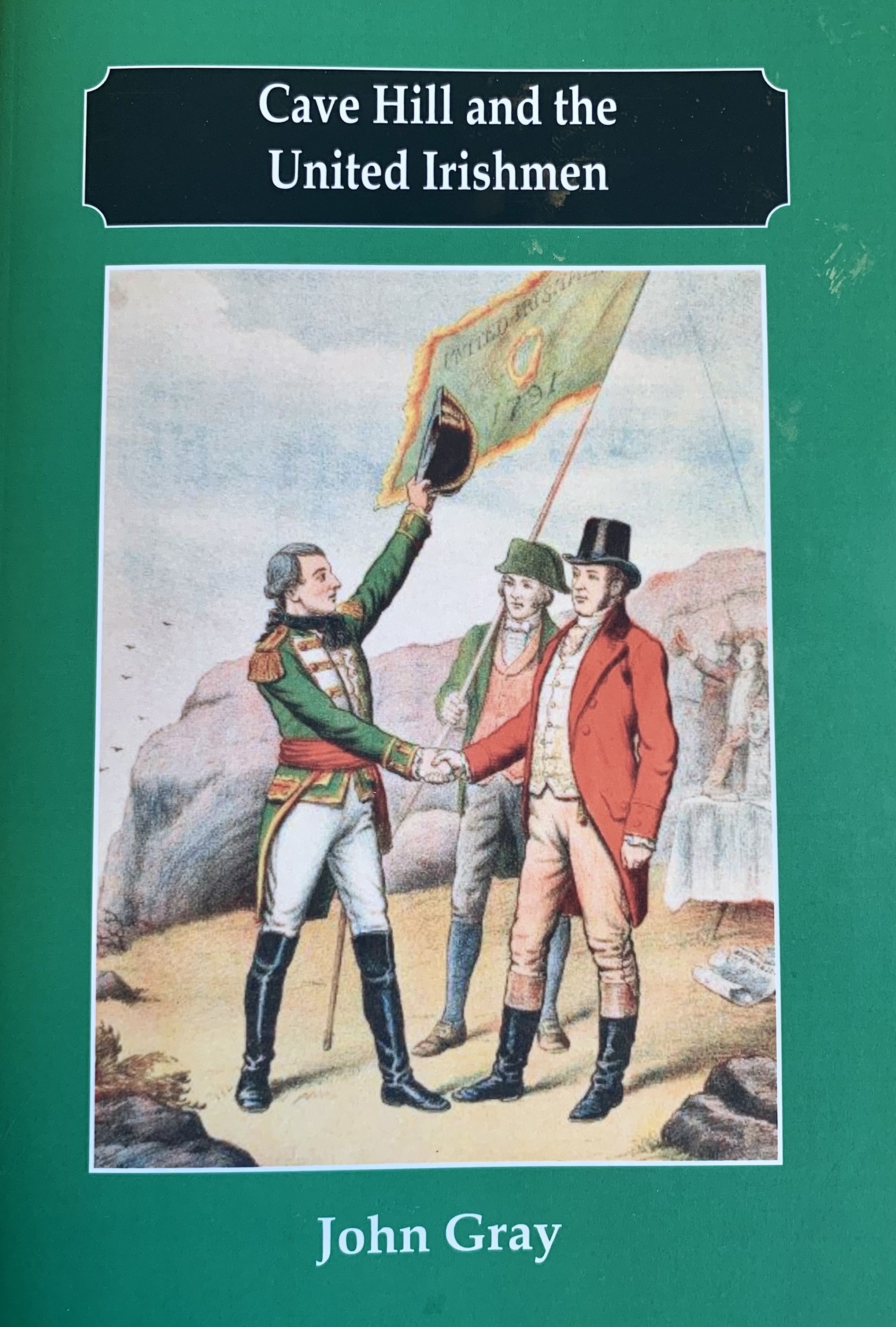

THE best kind of history is that which successfully brings the stories of our past to life. Recently I had the good fortune to buy three little books that do exactly that from An Fhuiseog on the Falls Road, beside Sevastopol Street. The three are Mary Ann McCracken 1770-1866 – Feminist, Revolutionary and Reformer; The United Irishmen and the Men of no Property, The Sans Culottes of Belfast; and Cave Hill and the United Irishmen.

Together they give a wonderful insight into the lives and working experience of those in the Belfast region who helped shape the United Irish Society of the late 18th century. They are all written by John Gray who is the former Librarian of Belfast’s Linen Hall Library. John Gray has written and lectured on “many aspects of Ulster’s Labour and radical history”. The pamphlets are written under the auspices of ‘Reclaim the Enlightenment’ which “is committed to recalling and celebrating that progressive era in Belfast’s past. We are convinced that doing so can lend inspiration in the present.”

Anyone born in Belfast or who has lived here even for a short time, is conscious of our Belfast Hills. These cradle the city and give it a spectacular backdrop. Foremost among these is Cave Hill, to the North of the city. It is a place long associated with the United Irish Society. Many of us are familiar with the account of the occasion in May 1795 when the leaders of the United Irishmen went to McArt’s Fort. Wolfe Tone recorded what happened there. “Russell, Neilson, Simms, McCracken and one or two more of us, on the summit of McArt’s Fort took a solemn obligation... never to desist until we had subverted the authority of England over our country and asserted her independence.”

Reclaim the Enlightenment- this Fri July 14 2-3:30pm Rosemary St Pres Church pic.twitter.com/8BNM1ttqEV

— Bill Shaw (@Billthunderroad) July 10, 2017

Through John Gray’s three pamphlets the men and the women of 1798 become more than just names on the pages of a book. The connections between Belfast – a town of around 20,000 people – and its hinterland of Carnmoney, Templepatrick, Skegoneill, Hightown and Roughfort rath, the first rebel assembly point in County Antrim that is only four miles from the Cave Hill – are described. So too is the plight of the tenant farmers and the growth of the first trade unions linked to the hand loom weavers, many of whom were from that locality.

In July 1792 Belfast celebrated the third anniversary of the French Revolution. There was a ‘Grand Procession’ with “citizens in pairs and people of the neighbourhood for several miles round, with green ribbons and laurel leaves in their hats.’”

Gray describes how one group was singled out. He writes: “namely, one hundred and eighty of the most respectable inhabitants of Carnmoney and Templepatrick. They bore a green flag, with the following mottos:

Our Gallic brother was born July 14, 1789; Alas we are still in embryo.

And on the reverse side:

Superstitious galaxy. The cause of the Irish Bastille; let us unite to destroy it.

“Their banner was designed by James Hope, a weaver from Mallusk to the west of Cave Hill, and later destined to become the most celebrated artisan United Irish leader...”

The central role played by Presbyterians and by women is also recorded in the pages of these pamphlets, one of which reflects at length on the life of Mary Ann McCracken. For a long time she was known mostly as the sister of Henry Joy McCracken, but Gray reminds us of her contribution as “a revolutionary, yes, as a feminist before the term was invented and as a social reformer.”

He writes, that Mary Ann “did not approve of separate women’s societies, though for entirely liberated reasons, arguing for the admission of women to the main societies, ‘as there can be no other reason for having them separate but keeping the women in the dark and certainly it is equally ungenerous and uncandid to make tools of them without confiding in them.’”

Three relatively short pamphlets. Full of information and detail about a pivotal moment in our history. I am happy to recommend these for anyone interested in the people and places and events that have shaped Ireland.