During the Covid-19 lockdown, St James’ man Liam McGrady put pen to paper about the impact of the Troubles on his family. From his brother Frankie on hunger strike and his mother’s correspondence with the British Government to the tragic murder of his brother Anthony (16) by the UVF and the family’s harassment by the British Army, this is ‘A Mother’s Untold Story of the Troubles’.

I SUPPOSE if you are going to write a story you might as well start at the beginning.

August 15, 1969. In our household in St James’, it was the youngest in our family’s birthday, the two twin boys, Paul and Gerard, but also the start of the Troubles. Unknown to us at the time was how the Troubles would have an impact on our family and what our parents, William and Anna, must have gone through raising a young family of six boys and one girl in a difficult North of Ireland.

I was only nine years old when the Troubles broke out, but on that evening I knew something was wrong. I remember our parents rounding us up and keeping us in the back garden.

There was Frankie (16), who worked in Mackie’s on the Springfield Road; Anne (14) who attended St Rose’s Girls School in Beechmount; Anthony (12) who attended St Thomas's Secondary School; myself; Liam (9); John (7); and the twins, Paul and Gerard, who had just turned five and were starting school in September.

Mum, Anna with twins, Paul and Gerard

Our father William (46) had just been pensioned off the buses in 1967 through ill-health. Our mother Anna was 43,) which nowadays is pretty young, but back then we all thought our parents were old.

Before we knew it, the British Army had moved in to protect us by putting barbed wire barriers up. As kids the Army were our friends. I remember my mother and all the neighbours in our street making them tea and sandwiches, giving them buns and biscuits and all the teenage girls running after them.

It was an exciting time for us as young boys. We were playing in the back of their lorries and jeeps. As a young boy, you always wanted to be a cowboy with a real gun. The Army let you hold their rifles and looking down the eyesights you thought you were John Wayne. What excitement – but all that was all about to change.

Overnight, just like that, everything had changed. The British Army had become our enemies. Before we knew it, barricades were going up at every street corner, such as old cars and lorries. Our parents kept us in, but when they let us out in the street to play, they gave us strict orders to play at the front door. Being a young boy with all the excitement, you wanted to be up at the street corners with all the big lads manning the barricades.

Before we knew it, we were up at the barricades playing in the old cars. For us kids, I guess we were too young to realise the dangers that lay ahead. The areas were known as ‘no-go’ areas for the British Army. Our parents must have been distracted because they realised the dangers that lay ahead for their young family in these troubled times in the North of Ireland.

It was August 9, 1971 when the government introduced internment. The new Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Brian Faulkner, decided to try out an old method of dealing with paramilitary violence. Internment was introduced but ended up having the opposite effect in the face of continuing violence.

Operation Demetrius started and 452 men were arrested, all from a Catholic background. All these men were innocent and were held without trial for years in Long Kesh. As we went from 1971 into 1972, the British Government give the go-ahead to the British Army to send the Paratroopers into Northern Ireland, a regiment known for their tough tactics.

They were deployed for an anti-internment march in Derry on January 30, 1972. The Paras ran amok and murdered 14 innocent people, which became known as Bloody Sunday, one of the bloodiest days in the history of the Troubles and the biggest mistake the British Government and British Army made as it was to be the biggest recruiting surge for the IRA and was probably one of the reasons why the Troubles went on into the 90s.

Stormont sat until March 30, 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore order during the Troubles, resulting in the introduction of direct rule from Westminster.

My mother and father were not politically-minded but I always remember my father saying he was as good an Irishman as anyone. I think that was my father saying that you don’t have to join an organisation to be a good Irishman as he was worried about us getting involved in the IRA after Bloody Sunday.

My brother, Frankie, now 17, was a young man and unknown to our parents got involved in the IRA. One thing led to another and before we knew it, the army were raiding our house looking for Frankie, who had gone on the run. To cut a long story short, the first night Frankie stayed in the house after being on the run, the army were tipped off by one of his friends, who was a British agent (a tout), that Frankie was staying with his parents. Our house was raided and Frankie was arrested. He was remanded in Armagh Prison and eventually he was sentenced to three and a half years for armed robbery for the IRA.

Armagh was about 42 miles from Belfast, so my mother had to depend on our father to run her to the prison on her weekly visit to see her son Frankie. Coming up to the third week of visiting Frankie in prison, our father's van was hijacked, burnt at Divis Flats and used as a barricade, which meant my mother had no transport to get up to Armagh to see Frankie.

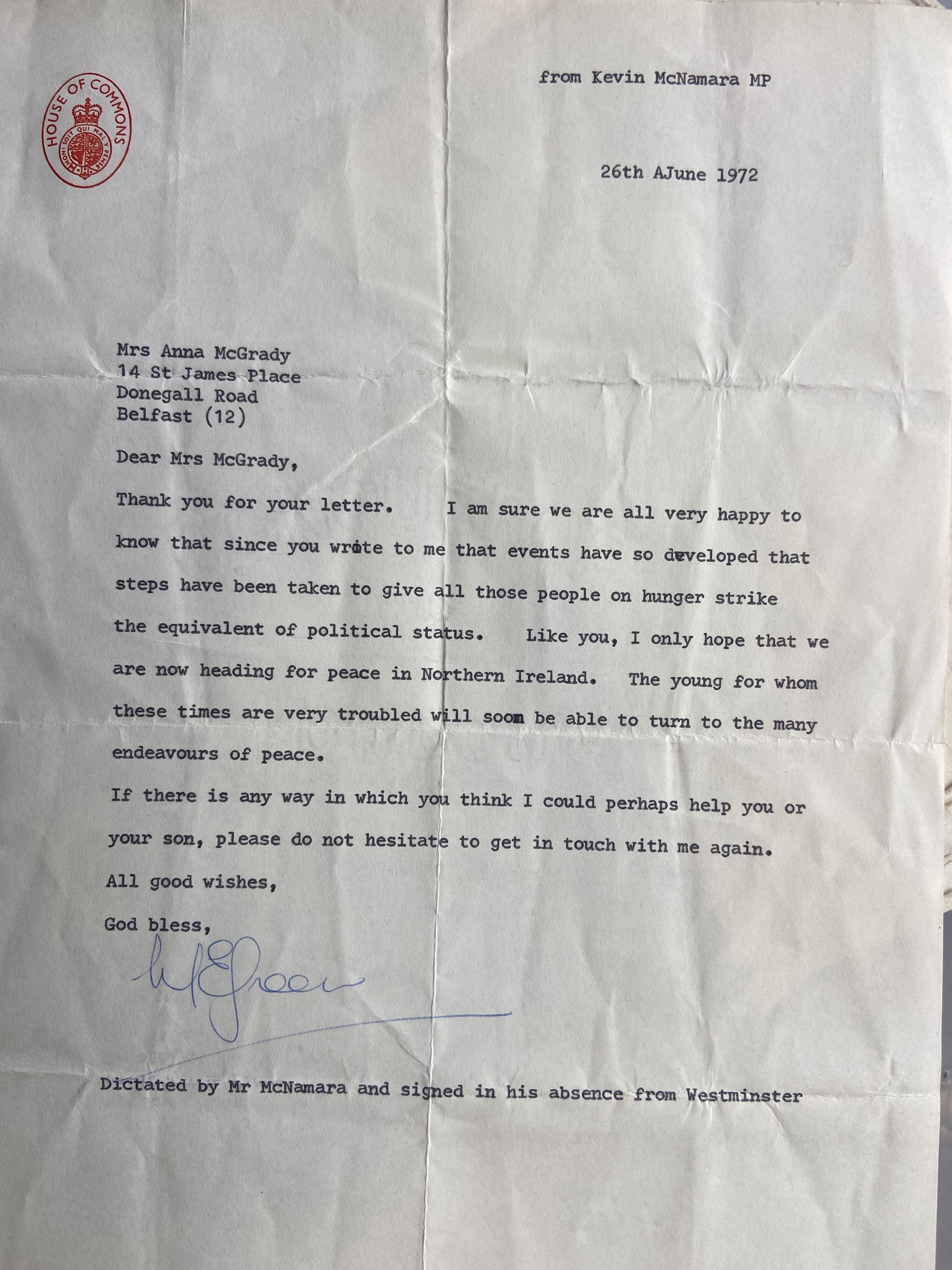

Mum was corresponding, writing letters to Labour MP Kevin McNamara, highlighting all the concerns for the prisoners on hunger strike, including Frankie, and the treatment of their relatives going to prison on their weekly visits. It wasn’t long before he wrote back to her.

In the letter, dated June 26, 1972, he said he hoped we were headed for peace, but peace was not to arrive for another 26 years!

A reply from Labour MP Kevin McNamara to Anna McGrady

Frankie was on his 23rd day of hunger strike when the first serving Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, William Whitelaw, gave special category status to paramilitary prisoners; in other words, gave them political status, and the hunger strike was called off. What mother and father must have endured during the time Frankie was on hunger strike, God only knows.

I am of no doubt that mother’s correspondence with Labour MP Kevin McNamara, who contacted his party leader, Harold Wilson, who was in direct contact with the Secretary of State, played a hand in bringing to an end the hunger strike of 1972 without loss of life.

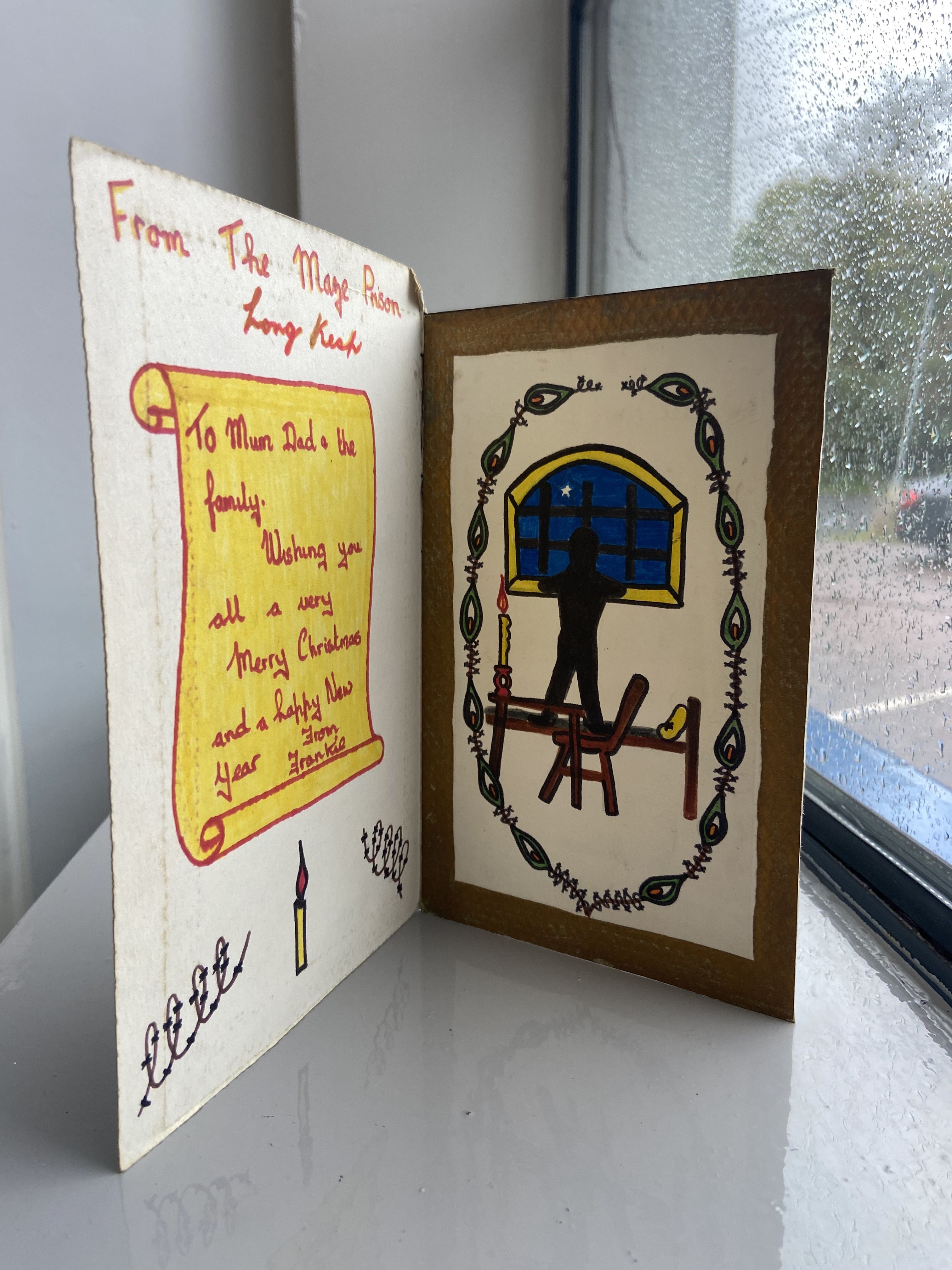

A Christmas card from Frankie to his family whilst in prison

My mother, who wasn’t politically-minded, had to rear a family of seven, worked tirelessly on behalf of the prisoners on hunger strike to achieve political status and highlighted the treatment of their families in prison units. Nobody else probably realised or noticed what she was doing behind the scenes.

As if our parents and family hadn't endured enough heartache, there was to be another twist. On Saturday, August 25, 1973, my brother, Anthony, was murdered for his faith.

As usual at about 2 o’clock on a Saturday, my father, Anne and Anthony arrived down in Omeath for the weekend. It was to be our last weekend together as a family, but it was a special weekend. Anthony had just turned 16, so my mother had a birthday tea for us all. We all went to the Hound of Ulster Hotel where we stayed to the end of the night until the band finished off with the Soldier's Song.

Little did our family know that this time next week, Anthony would be dead. A weekend of celebrations would be followed by a weekend of sorrow and heartache.

On Monday, August 21, my father, Anne and Anthony headed back to Belfast at around 8am. That was the last time my mother, Liam, John, Paul and Gerard saw Anthony alive.

Later that evening, my mother was agitated and suggested we go home as well. She said the next day she would make a flask of tea and sandwiches and we would all go up the Cooley Mountains to my aunt Christina’s cottage. It was about four and a half miles into the mountains and in the middle of nowhere. We got up the next morning, headed into the centre of Omeath to get lemonade and sweets and headed up the mountains.

The best way I could describe the journey was when in the Sound of Music film the Von Trapp family went up over the mountains and fields to escape the Nazis. We were like the Irish Von Trapps, only stopping to have tea and sandwiches. We arrived at Aunt Christina’s cottage, much to her amazement at how we found it. She was delighted to see us and we stayed to Friday. The plan was that my father, Anne and Anthony would be down on the Saturday for the opening of the outdoor swimming pool in Omeath.

Liam, Paul, Gerard and John in Omeath

But my mother was agitated all week. I know mothers can sense something. On the Friday, we said our goodbyes to Aunt Christina and started to make our way down the Cooley Mountains, into Omeath and back to our cottage.

On Saturday morning, Liam and John got up early and headed down for the opening of the swimming pool in Omeath. We were playing in the pool at around 12.30pm when Paul and Gerard came and told us we had to get dressed. We looked at them and said we wanted to stay in the pool for a little bit longer but they insisted we get dressed and that were going home.

I knew something was wrong. We got out and dressed. Our mother had heard a news flash on the radio about a bomb explosion at a garage on the Cliftonville Road. At the same time, the Gardaí had come and told her that there was an accident and we had to make our way home to Belfast.

Unknown to my mother, my father was on his way to Omeath with priests from Clonard Monastery in two cars to bring us home. My mother had to borrow money from a neighbour in the next cottage, a man called Tommy Whylie.

The Gardaí gave mum, Paul and Gerard a lift into Omeath and squeezed Liam and John into a patrol car. They brought us to the man who ran the Amusement Park and Zoo in Omeath. He was a bit of a hippy boy. He was also Omeath’s private taxi driver, so he ran us to Newry Bus Station.

From there, we got the bus to Belfast. Mum was in a very distressed state and as children we did not realise what lay ahead. She got talking to a lady on the bus about the situation. The lady then got up and spoke with the bus driver and he stopped the bus on the motorway at the Donegall Road and let us off. This was not a normal bus stop – the normal stop was Glengall Street.

We started walking up the Donegall Road and turned into St James’ Place. All our neighbours were out talking and then they started comforting mum. We ran into the house. It was packed. We were told Anthony had been killed. We were crying and I remember our cousins comforting us. Finally, my father and the priests from Clonard arrived and we were reunited in grief.

Saturday, August 25, 1973: a parents' nightmare when their son and our brother, Anthony, was murdered along with the two McDonald brothers, Sean and Ronald, at their garage on the Cliftonville Road in North Belfast.

RIP: Anthony McGrady (16)

Anthony was their young apprentice. They were shot and bombed to death. Their corpses were brought straight from the RVH mortuary to St John’s church on the Falls Road for 6.30pm evening Mass on the Monday. Tuesday was the burial at Milltown Cemetery after 11am Mass.

It was a tragedy. One of our family members was gone. Only when it happens yourself, you can’t put it into words. as my mother said. We were trying to come to terms with Anthony’s murder when we thought our parents and us as a family could not endure anymore heartache. But this time it came from the British Army, who came in the early hours of Friday morning to raid our house.

SIBLINGS: John, Paul, Anthony RIP, Gerard and Liam

I heard the banging on the door and my mother and father getting out of bed to answer the door. I heard my father arguing and my mother crying in pain, saying to them that we only buried our son on Tuesday and to leave our house. My father wouldn’t let the army get us children out of bed. They left after ten minutes, leaving my parents and children in a terrible state.

The following Friday, in the early hours of the morning, the British Army raiding squad banged the door again and got my parents out of bed, but this time got us children out of bed, as usual making us sit on the stairs while raiding the house.

They counted us and said to my parents that there was one missing. My parents said all their children were there and the Brits counted us again. One of them said: “Where’s Anthony?” The British Army were taunting my parents and us children about the tragic murder of Anthony, knowing fine rightly that he was murdered the previous week when they came and raided the house and left after ten minutes.

My father was arguing and my mother was screaming and crying in pain with a broken heart. My father told them they knew fine rightly what happened Anthony and demanded they leave our family home.

This routine went on for the next three weeks. The British Army raiding squad counting children, stating there was a boy missing. They were torturing and tormenting our family about Anthony’s death. The last time, as the squad left, my father jumped into his Morris Minor van and went out after them. Everyone knew that when they came to raid the St James’ area, they came from Broadway Army Post.

My father went in and confronted who was in charge of sending out the raiding squad to our home and said about them torturing and tormenting our family over Anthony’s death. Whatever he said worked. Our house was not raided for about two and a half years afterwards.

Our poor parents, what they endured during the Troubles. First, in 1972 with Frankie, aged 18 on hunger strike for political status, followed in 1973, when Anthony, aged 16, was murdered for his faith. And finally, the British Crown Forces tortured, tormented and taunted my parents and us children about Anthony’s tragic murder. Only the grace of God must have got my parents and us as a family through those horrific and troubled times.

Our father, William, died on January 17, 2003, and our mother, Anna, on February 28, 2006. I am sure they are re-united with Anthony in heaven. RIP.

This is my mother’s untold story of the Troubles.