THE news that Victims Commissioner Judith Thompson will not have her contract extended caused a mild flurry of media attention when announced last week. Of course, even a cursory look at the teacup’s storm would have recognised that Ms Thompson had already had her four-year term extended and another extension was unlikely.

But what’s the value of a Victims Commissioner? The first three were British Labour MPs, with the first, Adam Ingram, also holding the post of Minister for Armed Forces, a deliberate snub to victims of state violence.

In 2005 Secretary of State Peter Hain appointed Bertha McDougal as an “interim” victims’ commissioner. While Ms McDougal’s reputation remains impeccable, the appointment was not, and was later found to have been for “political purpose” when challenged by Brenda Downes in the Belfast High Court. The appointment had resulted from direct negotiation between Hain and Ian Paisley MP.

At @FeileBelfast 2020 we are joined by reps from @ShankillWomens @TRPNI @TJI_ & our own @Lesleyveronica to discuss conflict impact on gender & the LGBTQ+ community.

— Commission for Victims and Survivors (NI) (@nivictimscom) August 7, 2020

We ask if diversity & equality are at the heart of peace, are we there yet?

Watch at https://t.co/81NtLhbdje pic.twitter.com/cWCv57yCPM

Ms McDougal’s succession caused disquiet when four commissioners were appointed, in what was viewed by many as one commissioner for each of the main political parties. At the end of their term Ms Kathryn Stone was appointed. Ms Stone seemed unhappy with real politick of transitional Ireland. She resigned less than two years later. Judith Thompson was appointed in 2015.

While all of this is mildly interesting, what was happening with victims’ interests irrespectively was seismic.

Public inquiries into civilian deaths as a result of state violence and collusion. Prime Ministerial apologies for state wrongdoing. European Court judgments on state failures to deliver independent investigations.

Damning reports from the European Commissioner on Human Rights and UN Special Rapporteur for Transitional Justice on systemic failures to deliver to victims of the conflict. The Eames Bradley report, Haas O’Sullivan recommendations and the Stormont House Agreement. Structured development of hierarchies of victimhood through injured pension schemes.

And much more besides.

The past 15 years has been marked by continual promises to victims and survivors and not just no delivery, but deliberate and ignominious denial of rights. All of the responsibility for which lands at the grubby, granite doorstep of No. 10 Downing Street.

ADVOCATES: No one puts the case of victims than victims themselves, says Andrée Murphy. Ballymurphy Massacre campaigners outside the high court in Belfast. Today is the 49th anniversary of the Ballymurphy Massacre.

The expenditure of £1million per annum on a victims’ commission has affected this ignominy not one iota. The default Commission position has been silence, apart from the occasional appearance on television as a 'neutral' voice when matters of dealing with the past arise.

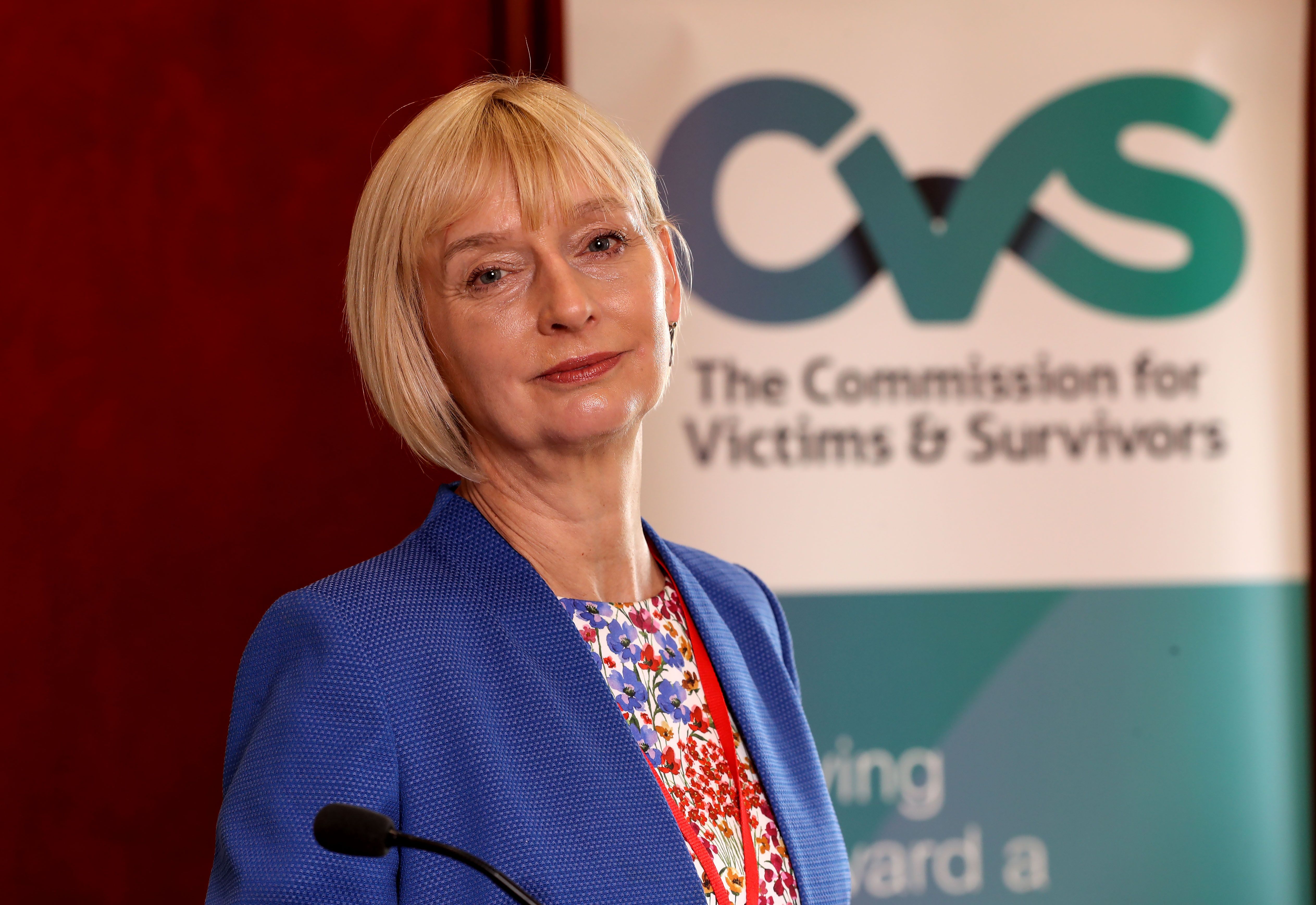

Victims Commissioner Judith Thompson has confirmed her term will end on 31st August.

— Gráinne Connolly (@grainne555) August 1, 2020

It follows speculation that she had not been reappointed for another term, after serving as Commissioner for five years.https://t.co/dMSxZH4kVj

Victims and survivors are their own advocates and that “dealing with the past” is at the heart of politics today, albeit belatedly, is because of the hard work and tenacity of bereaved families and the injured themselves.

With no one’s help.

Of course, a commission in this context serves a purpose. It displaces the voices of those who are engaged in victims issues and creates a barrier to their own effective advocacy. Why would someone paid a handsome salary, but not actively engaged in the issues affecting victims, be deemed more acceptable than the bereaved or injured themselves? Because the bereaved and injured make rooms uncomfortable.

They ask awkward questions and highlight the hypocrisy of the status quo.

'Commissions' on the other hand are designed to displace discomfort; they can be post-colonial hangovers serving to protect the status quo while giving a veneer of 'independence'.

Judith Thompson’s departure is an opportunity to re-evaluate and take stock. Perhaps it is time to decommission the commission.