THE people of Ireland have a long and proud tradition of opposition to slavery and colonialism.

On July 8 we celebrated the birth in 1770 of Mary Ann McCracken, a fierce opponent of slavery. She and her brother Henry Joe McCracken, one of the leaders of the 1798 Rebellion, campaigned against slave ships docking in Belfast port. In her late 80s Mary Ann was still a frequent visitor to Belfast docks where she handed out anti-slavery leaflets to those travelling to the USA where slavery still existed. Thomas McCabe, a United Irishman from the Antrim Road, was another stalwart who oppossed slavery and efforts to set up a slave trading company in Belfast.

In the 1840s escaped slave Frederick Douglass was warmly received when he toured Ireland speaking about his experience of slavery. He visited Belfast and spoke there. Daniel O’Connell was a leading opponent of slavery. This aspect of our history is especially relevant today as more and more people across the world speak out against modern slavery and racism.

The Black Lives Matter movement in the USA has led the way on this and there is now a focus on the role other countries played in the slave trade.

The British Empire, which at its height was the largest in human history, ruthlessly exploited hundreds of millions of people in Africa, India and elsewhere. Here in Ireland that imperialist British legacy is all around us. It is to be found in partition and the economic, political and human cost of that disaster. But it is also to be found in the symbols and statues and place names which are everywhere.

For example, for the ten years that I was a TD in the Dáil I parked each day in the shadow of a statue to Prince Albert, the consort of the English Queen Victoria. Have we no Irish heroes and leaders we could honour? In Belfast there are two bridges named after English queens. The Queen’s Bridge was opened in 1849 and is named after Victoria. The Queen Elizabeth Bridge is named after the current holder of that office and was opened in 1966. Interestingly there was a row among unionists in Belfast City Council who wanted to name it after Unionist leader Edward Carson whose statue stands in front of Parliament Buildings at Stormont.

There is the Craigavon Bridge in Derry – named after James Craig, later Viscount Craigavon, who was the first Unionist Prime Minister of the north after partition. In Belfast we have Royal Avenue and the Royal Victoria Hospital and countless other thoroughfares named after British royals or unionist leaders. There is Queen’s University and the Albert Clock, named after Victoria’s other half. Belfast City Council proudly erected statues and stained glass windows within the precincts of the City Hall reflecting this British and unionist dominance.

As societal, political and demographic changes have taken place and there is a greater understanding of the need for places to reflect the entirety of society and not just one section, some of this is changing. But it is very slow. In recent years there has been a campaign to use Irish street names and to erect Irish name plates.

A statue was erected on the Falls Road to James Connolly, not far from where he and his family lived for several years up to 1916 and his execution. There are also plans for a statue in the grounds of Belfast City Hall to Winifred Carney, an activist and revolutionary in her own right, who was with Connolly in the GPO.

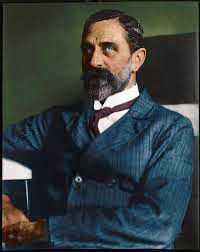

In Dun Laoghaire, outside Dublin, a statue is to be erected later this year to Roger Casement who was born in nearby Sandycove in 1864. Historian, activist and author Jim McVeigh has suggested a statue for Casement at the new Casement Park Stadium. I think that’s a good thought.

It would also be fitting in this current climate in which the colonial and imperial abuses of the past, especially around slavery, are being confronted.

1916 LEADER: The James Connolly statue on the Falls Road, Belfast

When the European empires in 1885 carved up Africa between them, Belgian King Leopold II was allocated two million square kilometres of land to run as his own private fiefdom. His rule, in what is now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, saw ten million and more murdered, and millions more, including children, maimed, their hands and feet cut off if they failed to obey the orders of his overseers. Leopold tried to keep others out of the region but the stories of torture and slavery and abuse gradually emerged. However, it was the work of Roger Casement which convincingly exposed Leopold’s reign of terror.

Roger Casement was raised in and around Ballymena in County Antrim. He was a member of an Ulster Protestant family, a Knight of the British Empire and a British diplomat. He was also a Gaelgeóir who loved the Glens of Antrim. He was proud to be Irish. He was a thinker who took many of the weightiest decisions of his life whilst pacing on Cushendall beach.

Casement was very conscious of the role and history of British involvement in Ireland. He was resolute in his opposition to it and his goal was a free, united and independent Ireland. During his time as a British diplomat he saw at first hand the impact of European Imperialism in Africa and South America. Casement wrote extensively about this.

In 1903 he was asked by the British government to produce a report on the conditions in the region controlled by Leopold. Leopold had established what he called the Congo Free State. He set up the Force Publique, a military body run by white officers whose job it was to ensure that the Congo’s vast wealth and resources were exploited in Leopold’s interests.

Rubber and ivory were the main produces. Indigenous workers were mercilessly exploited. Many died from exhaustion and hunger and disease working on the rubber plantations. Resistance was ruthlessly suppressed. Victims were often lashed using the chicotte, a whip made of sun-dried hippopotamus hide with razor-sharp edges. Most victims were given a hundred lashes, from which many died. Those who tried to escape or rebel were hunted down by the Force Publique who were ordered to cut off the right hand of anyone they killed.

During Leopold’s reign it is estimated that half the population of the Congo – or almost – 10 million people died.

Casement’s exposé of the cruelty of Leopold’s activities created an international outcry which led to Leopold being stripped of his control of the Congo.

Later Casement was sent to South America where he investigated the use of slaves and the ill-treatment of local native people by a British rubber company.

It was this record of work as a diplomat and a senior public servant for the British Empire which almost certainly sealed his fate in August 1916. More than any of the other leaders of the Easter Rising, Roger Casement was viewed by the British establishment as a traitor to his class and to the Empire. In a fortnight’s time we will remember the life and courage of Roger Casement, who was hanged on August 3, 1916.

The extent to which the British Empire exploited and killed and impoverished hundreds of millions is rarely told, especially by the British media. It is not a version of history taught in schools. But for the scores of nations, including our own, which are still faced with the legacy and challenges of that involvement, the current public challenge to the legacy of slavery and colonialism and Empire is an opportunity to ensure that the real story of the British Empire and Ireland is told and retold. Including how brave souls like Mary Anne McCracken and Roger Casement made a stand against it.