I HAVE spent many enjoyable afternoons in Casement Park watching countless football and hurling games – and playing in some of them. I have lost count of my Man of the Match triumphs. Especially for St Mary's or Belfast Schools in hurling. Or on Sports Days. In the past the stand and terraces or raised mounds around the pitch provided a wonderful view of the contests. Some games attracted a few hundred spectators while others were watched by enthralled thousands.

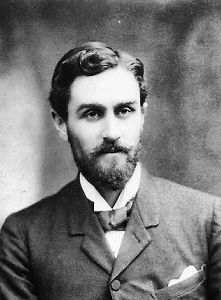

Casement Park was opened in June 1953 and was named after Roger Casement. He was one of the leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916, hanged in London by the British in August that year. The people of Belfast, but especially the West of the City, raised over one hundred thousand pounds to construct Casement Park.

For much of its 71 years Casement has been at the heart of the West Belfast community. At one point

At one point, classes for primary school children were held under the stand. On the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising in 1966 a huge and colourful pageant was held in Casement to mark that historic moment in Irish history. For a time after Operation Motorman in 1972 it was occupied for more than a year by the British Army. Rallies in support of the hunger strikers were held there also.

For the past eight years it has lain empty and silent as a legal battle was fought over planning permission for a new 34,000-seat stadium. That process is now at an end and last week the first steps were taken to allow construction work to begin. The decision by the Irish government to allocate €50 million toward the construction is a very welcome development. The hope is that the new Casement Park will rise phoenix-like within the next three to four years, in time to host the Euros in 2028.

Top Stormont official says Casement project is in 'good shape' https://t.co/cpoJhd3Vfw via @ATownNews

— Andersonstown News (@ATownNews) February 29, 2024

These exciting new developments got me thinking about Roger Casement. Who was this Dublin man who found a home in North Antrim and wanted to be buried at Murlough Bay near Ballycastle?

Casement was a member of an Ulster Protestant family, a Knight of the British Empire and a British diplomat. He was also a Gaeilgeoir who loved the Glens of Antrim. He was proud to be Irish. He was a thinker who took many of the weightiest decisions of his life whilst pacing on Cushendall beach. He was resolute in his opposition to British rule in Ireland and his goal was a free, united and independent Ireland.

Casement came to North Antrim after his mother died when he was nine. His father decided to bring the family back from England to live near relatives. His father died in Ballymena when Roger was 13. Roger remained in Ballymena, going to what later became Ballymena Academy. He moved to England at the age of 16 and eventually joined the Civil Service.

In 1903 he was asked by the British government to produce a report on the conditions in a region of the Congo controlled by the King Leopold of Belgium. Rubber and ivory were the main produces. Indigenous workers were being mercilessly exploited. Millions died from exhaustion, hunger and disease. Casement’s exposé of the cruelty of Leopold’s activities created an international outcry which led to Leopold being stripped of his control of the Congo.

Later, Casement was sent to South America where he investigated the use of slaves and the ill-treatment of local native people by a British rubber company. In 1911, for this work Casement was given a Knighthood by the British. However, his experience had also opened his eyes to colonialism.

Two years later Casement helped establish the Irish Volunteers. He travelled to the USA to raise money for that organisation and was involved in the smuggling of German weapons into Howth in July 1914. Casement negotiated with the German government during the First World War for more guns and assistance for the planned rebellion. He was arrested by the British at Banna Strand in County Kerry in April 1916, three days before the Rising took place.

He was taken to London where he was initially held in the Tower of London. Casement was viewed by the English establishment as a traitor. He was tried for treason and hanged on August 3, 1916. In his famous and powerful Speech from the Dock, Casement lambasted the English establishment. For England, he said: “there is only England; there is no Ireland; there is only the law of England, no right of Ireland; the liberty of Ireland and of an Irishman is to be judged by the power of England.”

#OTD in 1965 – Roger Casement’s body is re-interred in Glasnevin cemetery, Dublin.

— Stair na hÉireann | History of Ireland 🇮🇪 (@Stairnahireann) March 1, 2024

Read more 🔗 https://t.co/SwpWnqFRhE pic.twitter.com/9P21LckEXu

Addressing the divisions created by English governments Casement said that Irish Republicans: … “aimed at uniting all Irishmen in a natural and national bond of cohesion based on mutual self-respect. Our hope was a natural one, and if left to ourselves, not hard to accomplish. If external influences of disintegration would but leave us alone, we were sure that nature itself must bring us together.”

And on the right of the people of Ireland to independence and sovereignty Roger Casement told the court that condemned him to death: “Self-government is our right, a thing born in us at birth, a thing no more to be doled out to us, or withheld from us, by another people than the right to life itself – than the right to feel the sun, or smell the flowers, or to love our kind. It is only from the convict these things are withheld, for crime committed and proven, and Ireland, that has wronged no man, has injured no land, that has sought no dominion over others – Ireland is being treated today among the nations of the world as if she were a convicted criminal.”

In a letter from Pentonville Prison to his cousin, Elizabeth ‘Eilis’ Bannister, dated July 25, Casement wrote: “Don’t let my body lie here – get me back to the green hill by Murlough – by the McGarrys' house looking down on the Moyle – that’s where I’d like to be now and that’s where I’d like to lie.”

In 1965 British Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson agreed to the return of Casement, but only to Dublin. He was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. The new Casement Park will be a fine tribute to a great patriot. Let’s get it built.

Israel's starvation weapon begins to take its toll

THERE is now overwhelming evidence that the Israeli state has added a new weapon to its arsenal of genocide against the Palestinian people – hunger. The video and photographic images of starving children and desperate parents searching for food and water are heart-rending. The UN says some 2.3 million people in Gaza are now on the brink of starvation.

Palestinian people have been filmed eating grass in northern Gaza as emaciated children carry bowls hoping for some food in southern Gaza. There are reports of babies dying from acute malnutrition.

Jesus Wept! Ceasefire Now. https://t.co/Z5SNapglTl

— Gerry Adams (@GerryAdamsSF) February 29, 2024

We Irish have our memory of An Gorta Mór – The Great Hunger of 1845-52 – and of starving people eating grass. Some call it the Irish Famine, but in a famine there is no food due to some natural catastrophe. In Ireland there was plenty of food. During those years the quaysides of Limerick were lined each day with abundant produce including pork, oats, eggs, sides of ham and beef – all bound for export.

The reality and irony of this is appalling and was aptly described by George Bernard Shaw in his play 'Man and Superman'.

Malone: My father died of starvation in Ireland in the Black '47. Maybe you’ve heard of it?

Violet: The Famine?

Malone: No, the starvation. When a country is full of food and exporting it, there can be no famine.

And so it is in the Gaza Strip. There is plenty of food waiting in food trucks. More will be sent, but the Israeli state is deliberately blocking these. Starvation and hunger are now part of its strategy to kill Palestinians and drive them from their land. It cannot be allowed. Ceasefire now. We are all Palestinians.