SOME time around September 2007, a call came to my desk when I was doing research work on migration at Magee Campus.The man introduced himself as Paul from the Northern Ireland Office. He said that he had heard me speaking on a BBC Radio Ulster programme that morning.

He was interested to know if I could leave a specific date open. I said that would not be a problem. Of course I did not hear from him for over two months, because security checks were being done on me, I think. Then, in late October, I received a special invite from her Majesty the Queen to a Commonwealth reception that was slated for November 12, 2007.

Long story short, I met the queen herself, Prince Philip and Edward Duke of Kent (who I heard making small talk in a Nigerian-speak with a colleague, Anaka). Other notables were Sir Trevor McDonald, Archbishop John Sentamu and representatives of different commonwealth countries.

Queen Elizabeth II, the Head of the British State or the United Kingdom, had so many powerful constitutional roles that could have put the country in a reasonable place in the league table of human rights. We are talking about the period of her early reign. She had this absolute power which is mistaken to be ceremonial and this could have saved thousands of lives around the parts of the world that were under the control of the British empire.

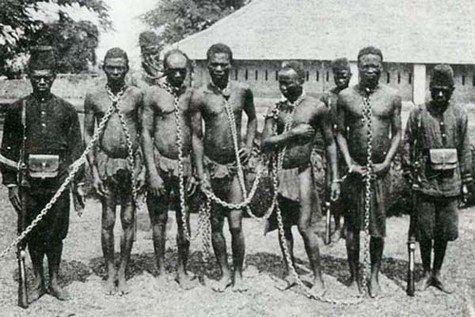

Yes, kings and queens carve out territories, grab them, rename these places and call them their possessions. King Leopold II of Belgium executed a bloody conquest of the Congo, a swathe of land bigger than the whole of Western Europe, then made it his playground by amassing everything that came to the way of Belgian expeditions. King Leopold physically owned a country that he never visited, not once. Queen Elizabeth II was the opposite. She visited these countries. She saw for herself what was happening.

The queen took the throne at the young age of 25. On important state occasions, she exhibited her power by placing on her head the African Cullinan diamond, the largest of that stone ever found. It was and still is incorporated into the crown jewels.

The relationship between the queen and her colonies was bound by this myth of the mystique of royalty, but in essence it was a story of plunder of poor countries in order to benefit rich and powerful nations. The difference between Queen Elizabeth II and the regime of King Leopold was very little.

Many royalists may argue, and fair play to them, that the occupant of Buckingham Palace follows what they are told, that nothing else is more important than God and the glory of the empire; that kings and queens are not subject to democratic practice, they are there by virtue of what position they are in the pecking order of their family. They are just pawns in a chess game that is controlled by their politicians and, they say, this is the case in Britain. They had no power to end the brutal colonial adventures around the world. It was the default setting that they must rule other countries by decree of the diktats of the Westminster Parliament and the office of the Prime Minister. In reality. it has always been the other way round.

The interests of the landed aristocrats who invaded Africa, for example, and many of whom were politicians, were paramount. The Englishman Lord Delamere and his descendants inspired thousands of colonial settlers into Africa using Africans for cheap labour and clapping for themselves for a job well done for the crown. It is this normalising of the crown assets, the empire, that made – and makes – the colonised feel permanently wronged. In Caroline Elkin's Britain's Gulag, there is endless bloodshed and nothing to celebrate about the crown in Kenya.

The late Queen Elizabeth II is of migrant roots from all over Europe. She had the power to change the direction and philosophy of empire to a single sovereign entity, Britain.

ellyomondi@gmail.com