AT LAST! Danny Devenny is doing a book. He will have to finish it now that this column has broken the story. It will be a photographic and literary journey through his very eventful life. In my opinion Danny Dee deserves a book or twenty books to celebrate his life in struggle and his art. He has enriched all our lives with his creatativity and brightened Belfast’s streetscape and educated and uplifted its citizens and visitors with his murals. He will tell how art has been a huge help to him through all his decades of activism. That’s where this painting, The Session, comes in.

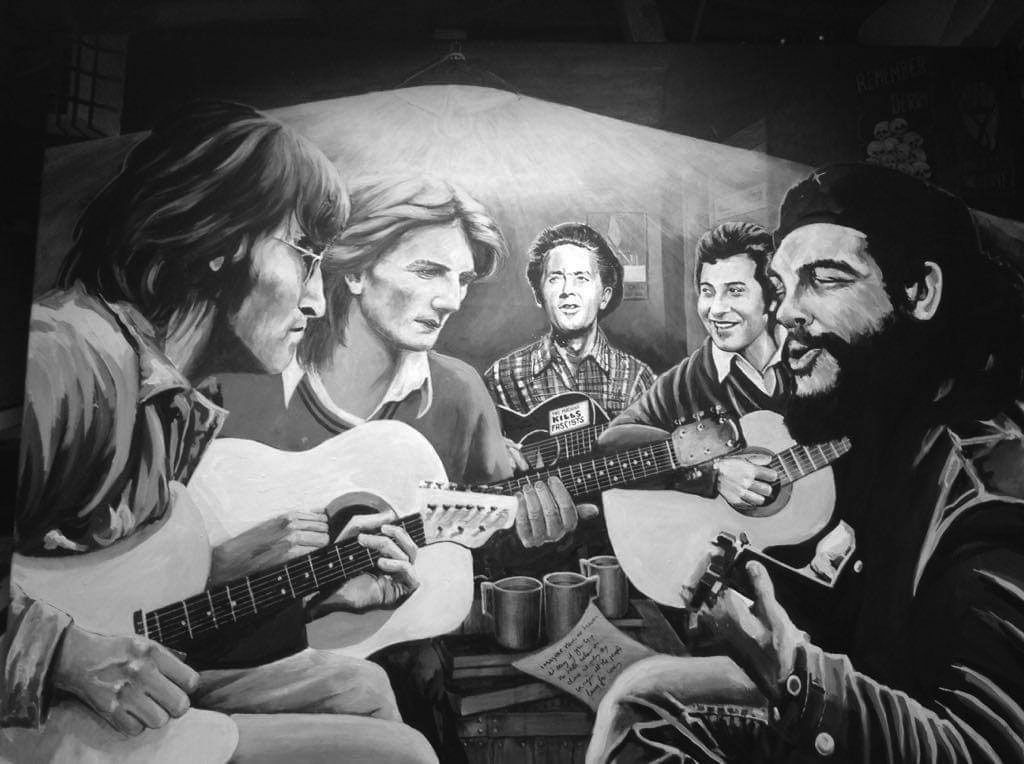

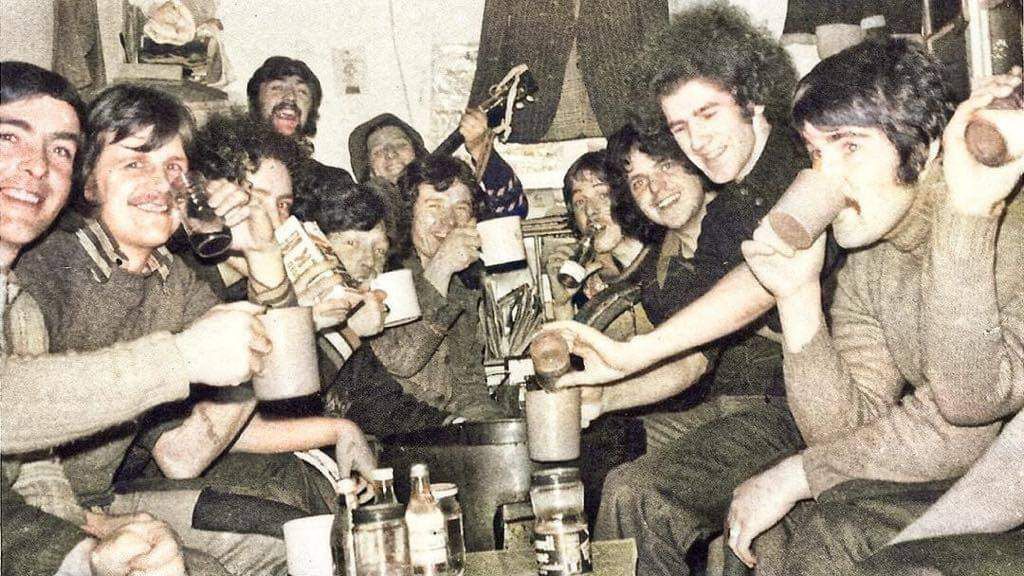

The Session features John Lennon, Danny’s friend Bobby Sands, Ché Guevara, Chilean activist song writer and poet Víctor Jara and Woody Guthrie, the great American song writer and activist. It is availible as a limited edition print and a not-for-profit funder for Danny’s book. Check out his Facebook page and private message Danny if you want to buy a copy. Danny has had a mind to do such a painting for a long time. He was in Long Kesh with Bobby and knows how much music meant to him. Bobby loved John Lennon. He would have loved being in a session with him. And the others. He admired them all. There is a photo of a session of poítín-drinking prisoners in Cage Eleven which Danny based his painting on. I will tell you the story of that photo and that session another time.

Anyway, Danny delayed doing the painting because he couldnt do a side view of Bobby’s face which satisfied him. Then Richard McAuley found the photo of Bobby in French photographer Gerard Harlay’s portfolio of photos when we were doing work on the Léargas book on Máire Drumm. That, and the pandemic, allowed the space for Danny Dee to work his magic.

I know the political value of that magic from my time in the Kesh with him in the mid-70s. Danny Dee did the artwork for a number of publications produced in Cage Eleven and smuggled outside. These included Peace In Ireland and Our British Problem – unpublished – by this columnist and In Care Of Her Majesty’s Prisons by Hugh Feeney and Prison Struggle. He also did illustrations for the Brownie articles which were smuggled out to the Sinn Féin paper Republican News. His pen name was Flossie.

Danny and Bobby were in the Gaeltacht hut in Cage Eleven. Bobby used to drive his comrades mad as he practised his guitar skills and learned his songs. Tomboy Loudon was just as bad. He was learning the mandolin. Bobby was taught guitar by blues legend Rab McCullough. They started in the Crum (Crumlin Road Prison) where there were two guitars. Bobby heard Rab playing and asked him for a few tips. Rab was already an accomplished guitarist. He had been in a number of bands, including Sunshine and The Big Soul Band.

When Tomboy and Bobby were moved to Long Kesh Rab – an exponent of Robert Johnson’s Delta Blues style–showed Bobby more tricks of the trade. He recalls Bobby was a big Rod Stewart and the Faces fan. He and Tomboy favoured Mandolin Wind.

They also picked up on Christy Moore. Ewan McColl’s fine ballad ‘Tim Evans’ was one of Bobby’s first songs. Christy’s renditions led him to Woody Guthrie. James Taylor, Neil Young, Dylan, Bowie, Loudon Wainright III and Leonard Cohen all influenced him. He used the melody of Gordon Lightfoot’s ‘The Wreck of The Edmund Fitzgerald’ years later in the H Blocks for ‘Back Home in Derry.’

He loved The Beatles, Especially John Lennon and Paul McCartney because of their songs on Ireland. When Lennon was threatened with deportation from New York, Bobby was among the prisoners who signed a petition in Cage 8 to support him. When McCartney formed Wings Bobby rehearsed ‘Mamunia’ until his hutmates dispaired. They threw oranges and apples at him another time, according to Paddy Donnelly, as he struggled before eventually getting the key change in Lennon’s Imagine. I recall him learning Kris Kristofferson’s ‘Bobby Magee’ in the study hut, just the two of us there, as I whiled away my time planning my next unsuccesful escape.

For their first Christmas in Long Kesh, in Cage 17, Tomboy, Rab and Bobby played at the Cage Concert. By the time they arrived in Cage 11 both Bobby and Tomboy had a reasonable collection of songs. When Coireall MacCurtain arrived in from Limerick and started Irish ranganna his teaching regime included a singing Rang. Bobby, by now a committed Gaeilgeoir, learned ‘Gleanntáin Ghlas' Ghaoth Dobhair’ and ‘Báidín Fheilimí’. He later went on to write his own songs i nGaeilge. There was only one record player in the Cage. Each hut got a go at it. Bobby played Prosperous non-stop and Clannad, Band On The Run and Bowie. By now his brother Seán had sent him in a guitar and song books.

I remember him playing and singing at our Cage concert the Christmas before he was released. Tomboy got out later and Bobby played at his homecoming gig in Unity Flats. He then suggested to Tomboy that they form a group. They did. Phoenix was their name. They had only two gigs. In the LESA (League of Ex-Servicemen’s Association) and Saint Matthew’s clubs. Then Bobby was re-arrested and Tomboy was back on the run.

Before then they had one good night down in Omeath. Tomboy recalls they ended up at a local wedding. A showband, The Four Aces, was playing and most of the older wedding guests were waltzing serenely as Bobby, his wife Geraldine and Tomboy watched. When Bobby went off to the gents Tomboy put his name down for a song request. He was duly called and, on borrowing a guitar from one of The Four Aces, Bobby launched into ‘Pinball Wizard’ by The Who. Tomboy says none of the waltzers applauded at the end. Suitably mortified Bobby told Tomboy with a big grin that it was like he was back singing in the Kesh.

All of this was before the horrrors of the H Blocks. So is the photo which Danny Dee used for The Session. He told me he wanted to show Bobby as he was– “A light hearted, funny guy.”

Thank you, Danny Dee. May your murals keep our heads high. Go raibh maith agat Bobby Sands. Let your music keep our spirits high.

Solidarity with the Palestinian People

A FEW weeks ago this column featured the hunger strike of Palestinian prisoner Maher al-Akhras. He was on hunger strike for a remarkable 104 days against his internment by Israeli authorities under their infamous ‘administrative detention’ system. Maher ended his hunger strike on November 6, following a commitment that he would be released on November 26 and not served with a further detention order.

Last Thursday he won his freedom and was taken to the Najah hospital in Nablus in the occupied West Bank. Maher’s courageous stand against the shameful system of administrative detention successfully brought the use of this repressive legislation to a wider international audience. It is also a reminder of the denial of sovereignty to the Palestinian people; the ongoing occupation of Palestinian land by Israel; and the apartheid system which most Palestinians are forced to live under.

Last Sunday was the ‘International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People’. This annual act of solidarity with the Palestinian people was agreed by the United Nations General Assembly in 1977 (resolution 32/40 B). It takes place on November 29 each year in remembrance of the resolution passed on that day by the UN which partitioned Palestine (resolution 181 (II)).

The partition of Palestine has created over 80 years of conflict and instability in that region. The human rights consequences for the Palestinian people have been horrendous. The Palestinian people are regularly denied freedom of movement, access to jobs, goods and services, including fuel and food and, in the midst of a pandemic, healthcare.

Three weeks ago in an act symbolic of the conditions endured by the people of Palestine, 73 people, including 41 children, were forcibly removed from their homes in the village of Khirbet Humsa and watched as Israeli military excavators smashed them into the ground.

The Israeli forces also destroyed 30 tonnes of food for animals and confiscated two tractors. It was according to the United Nations the largest forced displacement incident in four years. Yvonne Helle, the United Nations coordinator for the occupied Palestinian territory, said: “Demolitions are a key means of creating an environment designed to coerce Palestinians to leave their homes.” So far this year almost 700 structures have been demolished in East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

However, this Israeli tactic goes beyond demolishing Palestinian homes. For years it has destroyed EU-funded infrastructure projects in Palestine. Last year 127 structures, mostly funded by EU member states, were destroyed by Israeli authorities. In September 2019 EU member states spoke out against the Israeli policy of demolition. At the time they reported that “the period from March to August 2020 saw the highest average destruction rate in four years”.

At the same time the EU, which purports to support a two-state solution, is Israel’s number one trade partner. It also sells significant amounts of weapons to Israel.

The effect of this contradictory, confusing and ineffective stance by the international community allows the Israeli government to ignore protests and the demands of the United Nations for Israel to accept the rights of the people of Palestine.

The diplomatic and political policy of successive Irish governments in respect of the Palestinian people has failed. It’s time for a new strategy. In 2014 the Oireachtas voted in support of the Irish government officially recognising the state of Palestine and providing official Embassy status to the Palestinian Mission in Dublin. It’s long overdue that this was done. The FF/FG/GP government should also end their opposition to the Occupied Territories Bill – which would ban imports from illegal Israeli settlements in Palestinian territories. They should bring it back before the Oireachtas as soon as possible.