I HAVE known Tom Hartley for 55 years. During that time he has given decades of service to the republican cause. He has been an organiser, a writer, a propagandist, a leader. During the anti-internment protests of the early 1970s, and then the H-Block/ Armagh campaign, he was in the front line. He was Chair of Sinn Féin in Belfast and then during the hunger strikes in 1980 and 1981 he was responsible for the Sinn Féin Prisoner of War department, ensuring that we had a line of communication with the prisons.

In the 1980s Tom was Ard Runaí of the party. With the development of the Sinn Féin peace strategy Tom, along with Jim Gibney, led our effort to engage with political and civic unionism and the Protestant churches. Later Tom became a popular Belfast City Councillor and Mayor of the City.

Among Tom’s many talents – a bodhrán maker and player par excellence with a fine taste for good food and fine wine – he is also an historian who has written about the people and history of Belfast through his fascinating books on the City Cemetery, Milltown Cemetery and Balmoral Cemetery.

Tom decided many years ago that the republican history of the city – often ignored by the more established institutions – needed to be told and preserved. So Tom became a collector.

Posters, leaflets, badges, publications, books, speeches, in fact anything that wasn’t nailed down would find its way into the Linen Hall library for the perusal and preservation of this and future generations. Mostly republican, but his collection also reflects the differences of opinion and politics within our society.

In 2016 the Ulster Museum began its ‘Collecting the Troubles and Beyond’ project to which Tom has donated over 2,000 objects. Last week Tom opened his own unique collection: A Collector’s Story. At the well attended event he said: “If you’re not seen – you’re not heard. When you’re not heard someone else will steal your voice, either distort or silence your narrative.”

So, take the time to go to the Ulster Museum. You won’t be disappointed. Tom has made an invaluable and innovative contribution to the story telling of Ireland. Well done, a chara.

How I kicked the habit of a lifetime

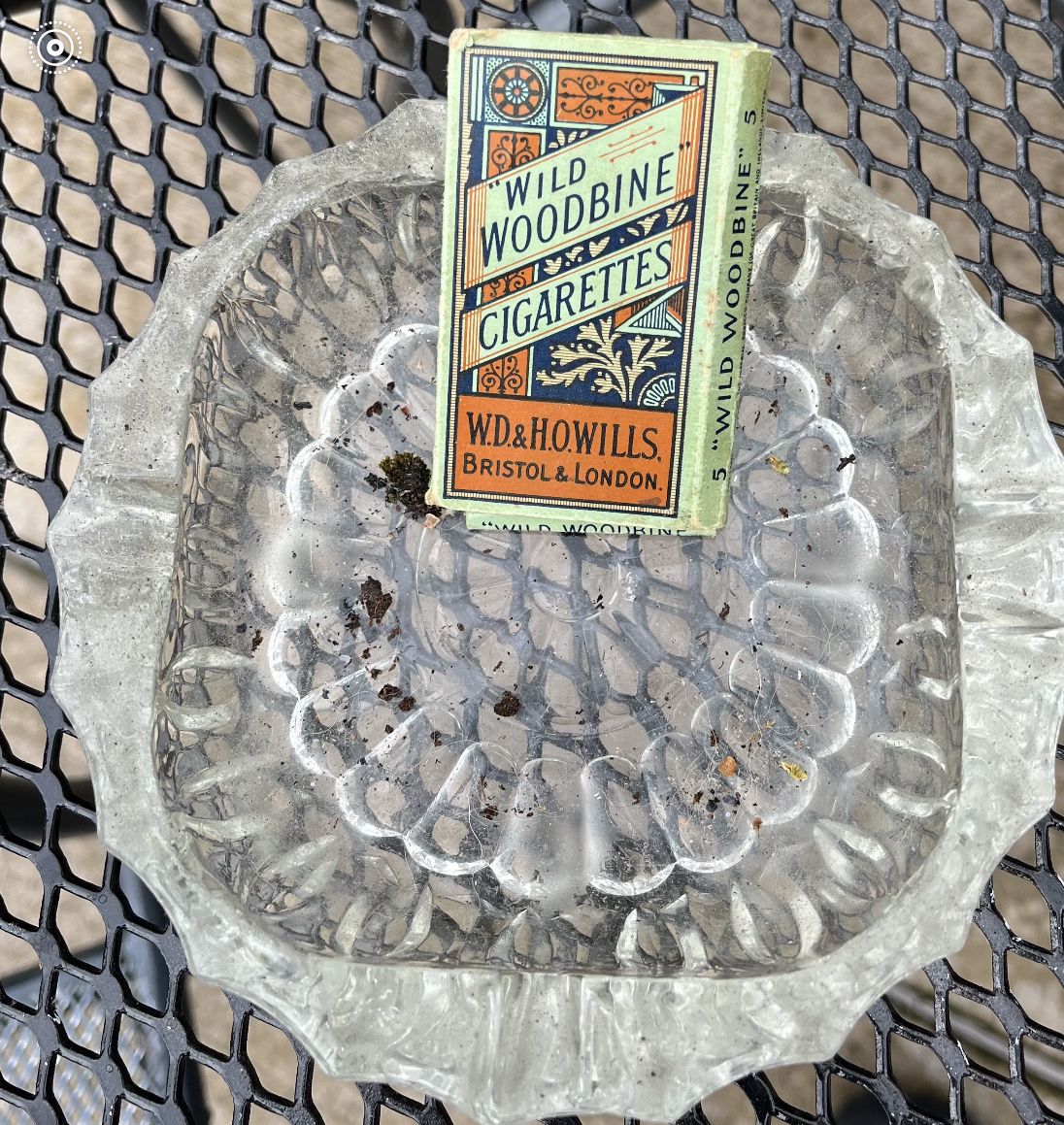

GASPERS: Woodbine untipped

BACK in the day my generation, or most of us, used to smoke. It was the social thing to do at that time. Gallaher’s Blues, Park Drive, Woodbine were the ‘fegs’ of choice. Some shops sold them as single cigarettes. Some were also available in packs of five.

I came upon an empty packet of five Woodbine recently. It sparked memories and a regret that I ever smoked. It was Joe Magee’s fault. Joe was a neighbour and a childhood friend. Joe is my pal to this day. He lives in Australia now. He introduced me to nicotine.

Later, when he joined the Merchant Navy, Joe brought home duty free Capstan, Benson and Hedges, Marlboro – I think that featured a cowboy in its adverts. He also brought Peter Stuyvesant and Camel into our lives. And our lungs. Once he went very arty with Gauloise Bleu before descending to rolling his own. Rizla cigarette papers wrapped around Golden Virginia tobacco. There was even a little machine for rolling cigarettes, complete with filter tips. When Joe and I started smoking, the now familiar filter tip cigarettes weren’t so popular.

Trips to Dublin introduced us to Sweet Afton and Major Extra Size, along with Carrolls Number 1. It seemed everyone smoked in those days. In this current smoke-free era it is hard to imagine how smoggy public places could be back then. Talk about smoke-filled rooms? Pubs and cafes vied with picture houses and concert halls, committee rooms and even changing rooms for that title.

And our houses were the same. Most homes had ashtrays. Some were rather stylish, perched on their own column of brass or glass or wood. Now they are rarely to be seen except as treasures on the Antique Road Show. Nowadays smokers stand outside in doorways and little shelters, like banished children of Eve, clustered together in all types of weather having a wee drag. I am told that romance often flourishes in these close encounters.

I used to smoke everything. Everything legal, that is. Cigarettes, cheroots, cigars, the pipe. Sometimes all at the same time. Well, not exactly all at once. My mouth isn’t as big as that, contrary to the claims of the usual jealous detractors.

Then I caught myself on. I started to try to give them up. I did it so many times I got good at it. Sometimes when I was trying to stop I used to keep a few fegs in a packet in my pocket. When the urge was on me to smoke I would take out a cigarette and talk to it.

“Do you really think you’re gonna break me?” I would ask it.

Sometimes that worked. Other times the cigarette faced me down. No matter how tough I talked it was well schooled in anti-interrogation techniques. It said nothing. I must confess, pardon the pun, that when I told the cigarette everything I knew about smoking and after I strenuously disassociated myself from and repudiated all connections with it, occasionally I broke and succumbed to the urge for one ‘last’ smoke.

It was the same in prison as it was out of prison. I struggled with my addiction. Cigarettes are a currency in prison. Especially among the Ordinary Decent Criminals, as the Brits call them to distinguish them from the political prisoners. Tobacco used to be king in those penal circles.

Toítíní was also a highly prized commodity for us politicos. Especially in punishment regimes where they were mostly forbidden. Or very scarce. I remember one comrade smoking tea leaves wrapped in toilet roll. He only managed two drags. Others scrounged discarded cigarette butts and shredded them into rollups. Sometimes using pages from the Bible. Holy smokes.

Colette smoked too. Though she confined herself to cigarettes. Then our oldest lad, alerted in school to the dangers of smoking, started to admonish us. So I stopped. But then I broke again. I never let on. It was a temporary lapse I told myself.

One day I was having a sneaky puff in the toilet. I neglected to lock the door. The oldest lad burst in. He caught me feg in hand. He was so let down and disappointed in me there was only one thing I could do. I stopped smoking there and then. One of the best things I ever did for my health. Go raibh maith agat, a Ghearóid.

Colette stopped as well, some time afterwards. But better late than never. Since then we live in a smoke-free zone.