NATIONALISM is in a bind. It has gained and maintained a significant share of the vote from unionism, and received enough transfers from Alliance voters to earn the First Minister position.

Unionism meanwhile has been in the persistent and objective minority with voters since 2017 and is likely to stay there. Neither the likeable Robin Swann and Mike Nesbitt could give the Ulster Unionist Party any significant bounce into the 21st century. The DUP remains so incalcitrant that their “take us as you find us” approach is the gift that keeps on giving to Sinn Féin. If opinion polls hold true the TUV is to become a third force in unionism, but will not expand the overall total unionist vote, perhaps even threatening to narrow it, with its stuck in the glory days of the sectarian statelet outlook.

But that does not answer the stubborn existential question for republicanism and nationalism. When Colum Eastwood said last week that the Assembly gets in the way of delivery of Derry, and he gets more achieved when it is down it struck a chord with many. There are obvious examples: The neutered anti-poverty strategy; four years for gynae appointments; and (say it with a sigh) Casement Park; for starters. But also, an unending inertia. In a time when global politics demands the progressive to be brave, the strictures of the Executive seems incapable of the modest. That is not powersharing, it is power avoidant.

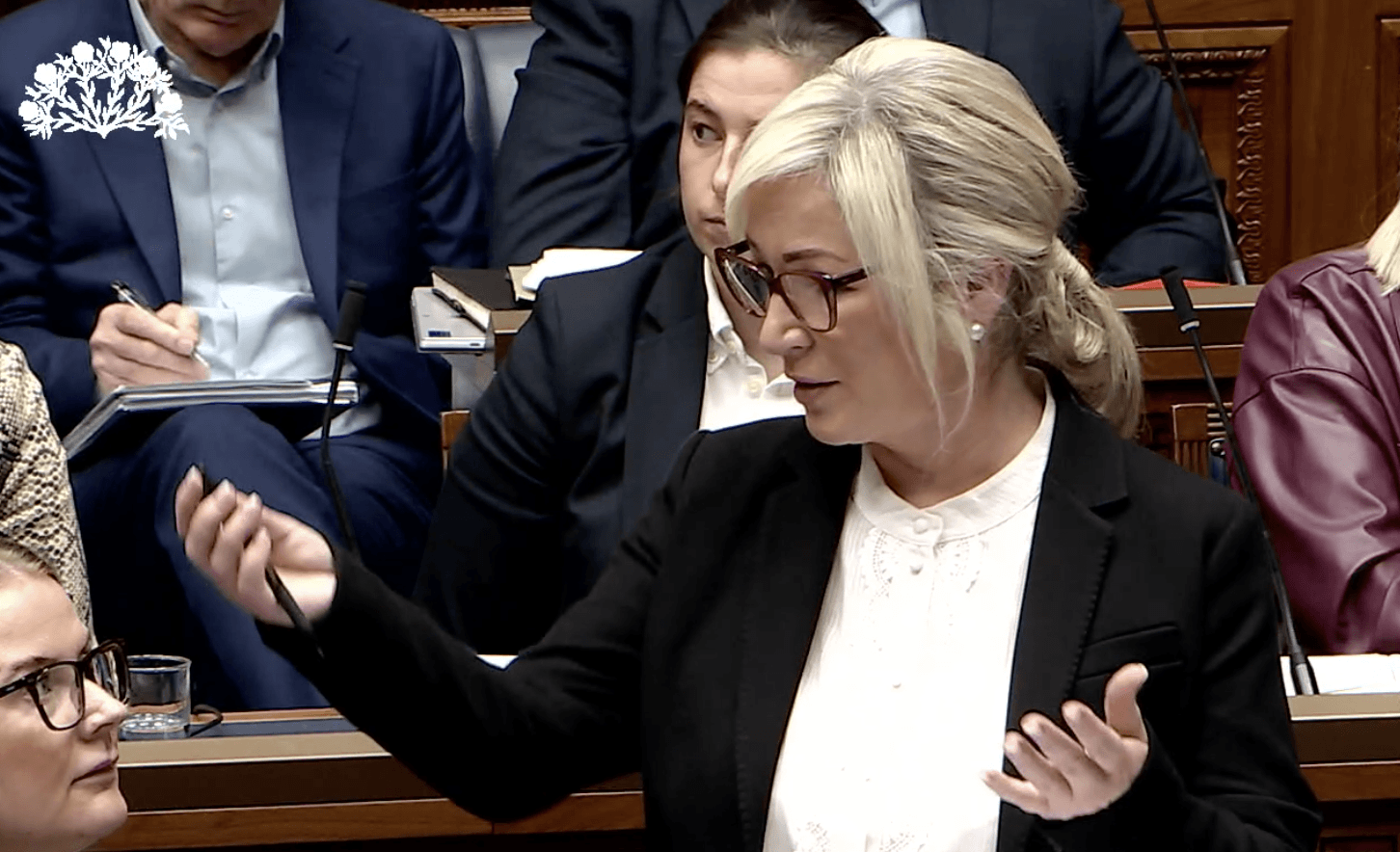

The Sinn Féin Executive team clearly wants different. Emma Little-Pengelly underestimates Michelle O’Neill and Sinn Féin. Ms O’Neill has proven time and again that she has no ego to pander to, and makes hard calls when required. In Sinn Féin statements, and policies, they want to be a very different form of government, but being restricted by the DUP’s never-say-yes attitude, and by the British government, is at the heart of a fundamental challenge. The British government wants the North to be a part of Britain but that means keeping it on life support, and unable to thrive. Like a coerced flower in the attic, it is the most abusive of relationships.

For the SDLP the position is worse. Knowing that the Assembly project is broken yet acting in opposition, not to the institution itself but to those who are trying their best in a place that is incapable of fully delivering, is like bemoaning the speed of horses when you are unable to afford a truck.

And thus the republicans and nationalist bind. Their constituencies have less than no faith in this strand of the Good Friday Agreement. Their parties are suffering with public confidence deficits as a result. But they are both worried about calling time. How far can they acknowledge “yeah this is a basket case” which many feel, while still publicly appearing positive and hardworking? Irish unity solution is the evident solution to all of this, but we don’t have the Border Poll date. So how does Sinn Féin and the SDLP remain positive in a broken arrangement which can never work because it is dependent on London, and whose interest it is to keep us broken?

Part of the answer will undoubtedly be to call it out. The time is fast approaching when a hard call will be made. However, what that might be is unclear, as yet.