Dee Walsh hung up his gloves at just 25 despite looking set for big things in the sport, but six years on he finds himself as the man guiding fighters’ fortunes

BRUTAL knockouts or feats of strength and bravery may define boxing for many, but the basic premise of the noble art is to hit and not get hit.

Floyd Mayweather Jnr was the greatest proponent of this approach throughout a career that saw him retire undefeated, with former opponent Ricky Hatton claiming he ‘couldn’t hit him with a bag of confetti’, such was the defensive genius of ‘Pretty Boy’-turned-’Money’.

Of course, ‘protecting the 0 (undefeated record)’ is one feature of the Mayweather era that has been something of a blight on the sport, but the defensive nous and counterpunching was not lost on a young boxer from St James’.

Dee Walsh spent countless hours studying the craftsmanship of Mayweather and other greats of old, making notes and perfecting those methods in the gym that earned him a reputation as one of Irish boxing’s best kept secrets during an all-too brief career in the ring.

On his night, ‘Waldo’ was mesmerising and seemed destined for big things in the sport but by the age of 25 the gloves were hung up forever.

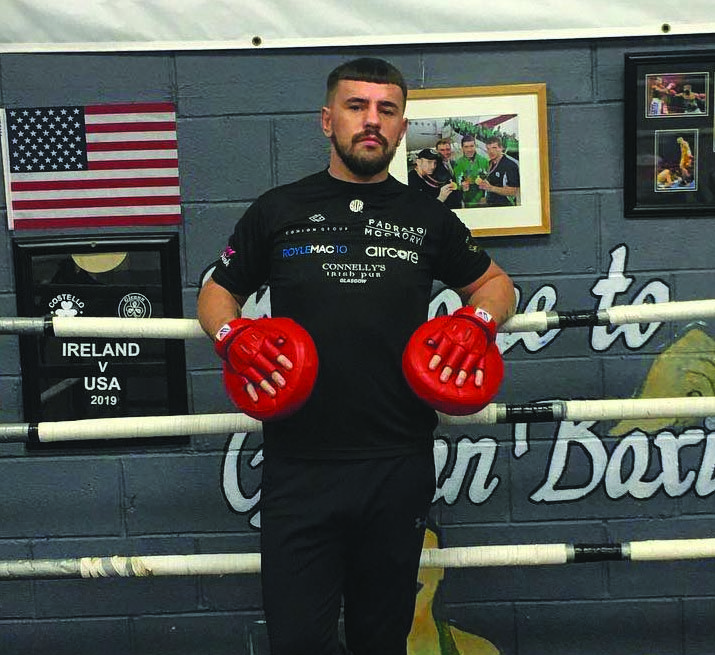

Now at the age of just 31, it is the pads that adorn his once vicious paws and despite spending fight night outside rather than inside the ropes, he wouldn’t have it any other way.

June 6, 2015 was a night those in attendance at the Devenish Complex will hold bittersweet memories. Walsh had just produced a jaw-dropping display to bamboozle Patryk Litkiewicz over eight rounds, but below the surface the fire was burning out.

The St James’ man always came across as a deep thinker, softly spoken but with a mean streak inside the squared circle. He had battled his inner demons for years and on that June night, he appeared to be a man in total control of his destiny, but all was not as it seemed.

“I think my last fight was my best-ever performance, but I could have been even better that night if I had trained properly,” recalls Walsh, whose life has now taken a new path as a born again Christian and boxing coach of professionals and young amateurs.

“I remember being really nervous before that fight as it was around that time I started to fall out of love with boxing.

“At that time, I would have trained twice a day, five times a week with (coach) Gerard McCafferty, but by then I had stopped doing the second session and was dreading the next one.”

**************

Boxing wasn’t something on the radar of a young David Walsh who grew up in the St James’ area of West Belfast. In his early teens, his scrapes took place on the streets rather than in the ring, which led to unwelcome attention.

Dee Walsh’s best performance came against Patryk Litkiewicz in June 2015, but it would prove his last

Having crossed the line once too many, he had drawn the attention of local paramilitaries who would impose a curfew. With a threat hanging over his head, a sense of direction was required, and the answer was to be right in front of him.

Both he and best friend Ruairi Dalton both had older siblings who were talented boxers, and it was only natural they found themselves following that path to the Holy Trinity club in Turf Lodge.

“I wasn’t allowed out of the house past 7pm so I just thought I may as well take up boxing for something to do. As it went on, I got better and better at it, then really started to enjoy it.”

The enthusiasm would develop over time and by his mid-teens, Walsh would discover he had a real aptitude for the sweet science that would translate into ring.

He admits it took him until he turned 16 before he really began to put in the hard yards and that would pay off over time, earning a green vest to box for Ireland two years later that would push him onto greater heights.

“I really didn’t start to get better until I boxed for Ireland when I was 19. I started to excel then as I had been boxing at Elite level for two years and getting nowhere. Before that, I had lost seven out of nine fights, but until I finished as an amateur, I had 30 fights and won 28 of them. I started adapting that Floyd Mayweather style with the hands down and began to enjoy it.”

The amateur middleweight rankings from Boxing News in 2010 had Walsh at number four

The style that defined Walsh was forged from watching grainy images of the sport’s all-time greats such as Jack Johnson, Marcel Cerdan, ‘Sugar’ Ray Robinson, Muhammad Ali, Mike Tyson, Willie Pep and Roy Jones Jnr whilst passing time working in a barbershop in his late teens and early 20s.

Once he had clocked off from his day job, it was straight to the gym for training before returning home for the night to settle in and return to study.

“I would have watched Floyd Mayweather after training at night. It was when I was 19 when I started thinking that if Mayweather has a perfect record, then why don’t people start boxing like him? That was my thought process as by the time I was 19, I had some of the most embarrassing losses I ever had. Had it have been a year later, I would have stopped them and that’s how much I had progressed.

“That is what has given me a head start as a coach as I still have everything I had written down about those fighters.”

By 2010, Walsh was ranked fourth in Boxing News’ amateur middleweight rankings for Britain and Ireland.

The previous year, he had annexed the Irish U21 title, beating four champions along the way including European Schoolboy gold medallist Stephen O’Reilly in the final.

He would come up short against Eamonn O’Kane in a close-run Ulster Elite final that would ultimately cost him the middleweight slot at the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi, despite defeating club-mate Conrad Cummings and then Connor Coyle in subsequent box-offs.

With the Games now out of reach, Walsh went on holiday, but disaster would strike as he broke his hand on a punching machine that would sideline him for a year.

By the time 2011 rolled around with Olympic Games qualification on offer, he found himself in a battle to simply be in a position to enter.

“Micky Hawkins (club coach) told me about this qualifier, and I thought: ‘ok, I have a short period of time to lose this weight, but I’ll go for it.’ I lost the weight, but unhealthily, then ended up fighting Conrad Cunnings but was totally gassed after 30 seconds and lost.

“After that, I thought there was no point hanging about (at amateur) as the next Olympics were in 2016 and around a month later, I was making my pro debut against Gerard Healy.”

Dee Walsh in action against Gerard Healy on his professional debut back in 2011

Cork’s Gary Hyde had secured the signature of the slick St James’ man who would trade leather with fellow West Belfast man Healy at the King’s Hall in September 2011 on a card topped by Tyson Fury.

“I remember being really depressed when I lost to Conrad as I was ranked higher than anyone in England, Scotland or Wales at the time and then I was number two in my own club.

“It turned out to be a blessing as Tyson Fury was coming to town and I was on his bill. Thinking back when I turned pro, they were great days and I started to think I was glad I didn’t qualify for the Olympics.”

Walsh would score a points win over Healy and then go onto enjoy a productive 2012 with wins over Lee Noble, Tommy Tolan, Julio Sanchez and then one year and five days after his debut, Robert Studzinski on the undercard of Carl Frampton versus Steve Molitor.

Excitement was beginning to build around the slick, yet venomous Walsh amid Belfast’s fight fraternity, but having just become a father for the first time, the realities of life would take charge with boxing not paying the bills.

At 5-0, it seemed a crying shame that would be it for a man with so much potential, but 20 months later, he was back in the ring.

“I had been training with Tony Dunlop in the Kronk Gym, and James Tennyson and Dan McShane were in there too, so Mark (Dunlop, manager) was always knocking about.

“He contacted me on Facebook about how I could fit boxing in, and I just thought that the wee lad was one at the time and that I would juggle things between being a father and a fighter. I really enjoyed 2014 as I was constantly training and fighting.”

The long-awaited return took place at The Devenish on May 5, 2014 and Walsh wasted no time on announcing he was back, blitzing Krisztian Duka in 116 seconds. Following three further victories, he was back at the Finaghy venue on November 22 to take on Terry Maughan for the Irish light-middleweight title and having displayed his silky skills in the opening round, turned up the heat in the second with ruthless efficiency as he closed the show in 68 seconds of the round as his vicious streak came to the fore.

If that was good, then after another early night against Peter Orlik, he would put on that masterclass against Litkiewicz, dominating for eight rounds where his movement, skill and ability to slip and dodge anything that came his way left all in attendance purring. However, this display would mask what was happening in the background and ultimately, would prove his last dance.

Walsh after his Irish title win against Terry Maughan in November 2014

With his desire to fight again on the wane, a holiday in the United States later that tear would see the Belfast man look to reinvigorate himself when passing through Las Vegas.

Mayweather’s opulent lifestyle and feats in the ring had left a mark on Walsh who was keen to emulate his hero, adopting a similar style in terms of boxing and ring attire.

It was just over a week before Mayweather would take on Andre Berto in his 49th fight and Walsh intended to use a workout at the Mayweather Boxing Club to rekindle his love for the sport.

However, the adage ‘never meet your heroes’ would ring true and the experience would confirm that his fighting days were over.

“I remember when I arrived and was paying in, the guy at the door said to me that Mayweather would be there in an hour.

“At the time, I thought it would be like meeting God as I idolised him and watched every one of his fights from 2001, but in the end I didn’t even watch his last fight.

“I just saw the way everyone in the gym was getting on, acting like him and trying to copy him. It made me think that it was how I’d been acting over the past few years as I wasn’t just trying to copy how he fights but re-enact how he behaves outside the ring and the thought of that made me cringe.

“I tried to speak to one of the fighters and got blanked, then it was the same with Roger Mayweather, who I idolised. After about half an hour of that, I just walked out of the gym. I had gone there hoping to reignite the fire in me, but after that it was out.”

If Mayweather was previously a God to Walsh, after several months of soul searching, he would connect with the real deal.

“I am a bit of a deep thinker and that would benefit me as a coach, but in so many other ways.

“At the time when I was fed up with boxing, I started to think about things and began researching things. I started to think if there was a God or not, and then came to the conclusion that the God of the Bible is the most solid, and I then became a Christian.”

It wasn’t his faith that led him to hang up the gloves, however. That fire had since burned out and whilst some in the Christian community may feel that faith and fistic fury shouldn’t mix, there are many examples of fighters of faith including George Foreman, Evander Holyfield, Andre Ward and Manny Pacquiao to name but a few.

“Boxing brings a lot of positives to people’s lives.

“If it wasn’t for boxing, God knows where I would be now. I see people who used to be in boxing who are in jail now and have been, so it has helped me to stay away from that path.”

**************

Young fighters may look to the sport’s superstars who enjoy the fame and fortune that comes with their achievements, but that lifestyle is reserved for just one per cent of those who punch for pay.

Instead, the reality for the vast majority is that any money earned comes from the ability to sell tickets and this aspect of the job is one that brings its own pressures.

Walsh recalls countless hours spent after weighing-in until just hours before making the walk to the ring trying to shift tickets to bolster his modest fight purse. His old friend Dalton would lend a helping hand, but this side of the sport was one that never sat well and he recently spelt the situation out in a typically honest social media post, apprising those who may be considering pro boxing as a career path with the realities of what it involves.

“It is a hard sport in every way: mentally, physically and then there is the business side.

“That experience has benefitted me as a coach as I know about that side of things. I know what it’s like to feel depressed after a loss or having to get up for training when you don’t feel like it.”

Walsh with Lewis Crocker having guided the South Belfast man to the WBO European welterweight title back in August

With an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of the fight game having been engrossed since lacing up the gloves, returning to the gym in a training capacity was a natural fit as Walsh initially teamed up with Ray Ginley to train Lewis Crocker in 2017, but has since branched out on his own with Crocker once again under his guidance.

The adrenaline rush of fighting had been replaced with the thrill of guiding fighters who will undoubtedly benefit from working with the young trainer who is wise beyond his years.

“When one of my fighters win, I feel like I win.

“There’s a feeling of relief and that you’ve accomplished something, especially in the 50/50 fights. I think those fights being out the best in me and help my fighters trust me more when they win them.

“It’s not certain, but ‘Pody’ (Padraig McCrory) and Lewis (Crocker) have fights coming up later in the year with a couple of opponents mentioned, so I have already started to study them so I will know what the game-plan is going to be for the next two months, so they know when they walk into the ring, the game-plan they have is what they’ve been working on for two months.”

As-well-as the aforementioned duo, lifelong friend Ruairi Dalton, Owen O’Neill and a new face in Conor Quinn are under Walsh’s tutelage as he imparts the wisdom gained from a lifetime practicing and studying the sport.

His ‘hit and don’t get hit’ style, mixed with the natural power of McCrory and Crocker has already yielded impressive results for both men and the graph looks set to rise further.

“I would jump in and do a couple of rounds sparring at times and did with Lewis before his (WBO European title) fight with Louis Greene to show him how he would fight.

“I’ve had a few fights with Lewis now and have just tried to make a few small changes to what he does. Boxing is about hitting and not getting hit. Lewis has a brilliant ring IQ and punching power, so I hope he can go far.”

Just what this year will bring is anyone’s guess as the Covid-19 pandemic continues to disrupt boxing’s schedule.

That disruption is not exclusive to those who fight in the paid ranks, but also Walsh’s stable of young amateur fighters which now totals 10 in all. He trains his pro fighters in the morning before moving onto his young charges in the evening and has identified 12-year-old Ulster champion Jordie Cooke as a huge talent.

The sport was a beacon for him in his teenage years to steer him back onto the right path, so his worry is that with competitions and scheduled training will see many drift away from the sport permanently.

“I love being busy with the pros and the amateurs as I want to throw myself into the deep end and get more experience, learning new things.

“The sooner we can get going, the better as I really miss it. And for the kids, it would be disheartening to see them go away from the sport as there has been nothing happening for a year. I know myself you can drift into bad things and that is something I don’t want to see happen to kids.”

It has been quite a journey for Dee Walsh to date: from the tearaway teen to a slick boxing technician and now a coach who mentors up-and-coming talent having chosen God over a false prophet. He still gets messages asking if there is a chance of a comeback as a fighter, but those days are in the rear-view mirror. ‘Hit and don’t get hit’ remains his boxing philosophy, but now it’s about spreading the word.