IN 1845 the Belfast ‘Banner of Ulster’ described Smithfield as “All that wild wilderness of lanes, alleys, blind courts, and ‘rows’, lying between Hercules Street and East Smithfield and bounded, on the other side, by Berry Street and North Street, forms one of the most extensive and gangrenous of these social ulcers. There, in foul and fetid huts, unglazed-ragged, drunken-looking ranges of buildings that seem like tipsy wretches arming one another along – swarms of hideous women and children who are virtually orphans under their parents’ roof find refuge but not shelter. Here, amid pools reeking with malaria and heaps of putrefying offal, the refuge of slaughter houses, typhus in its most malignant forms, cholera, angels of death ever hover...”

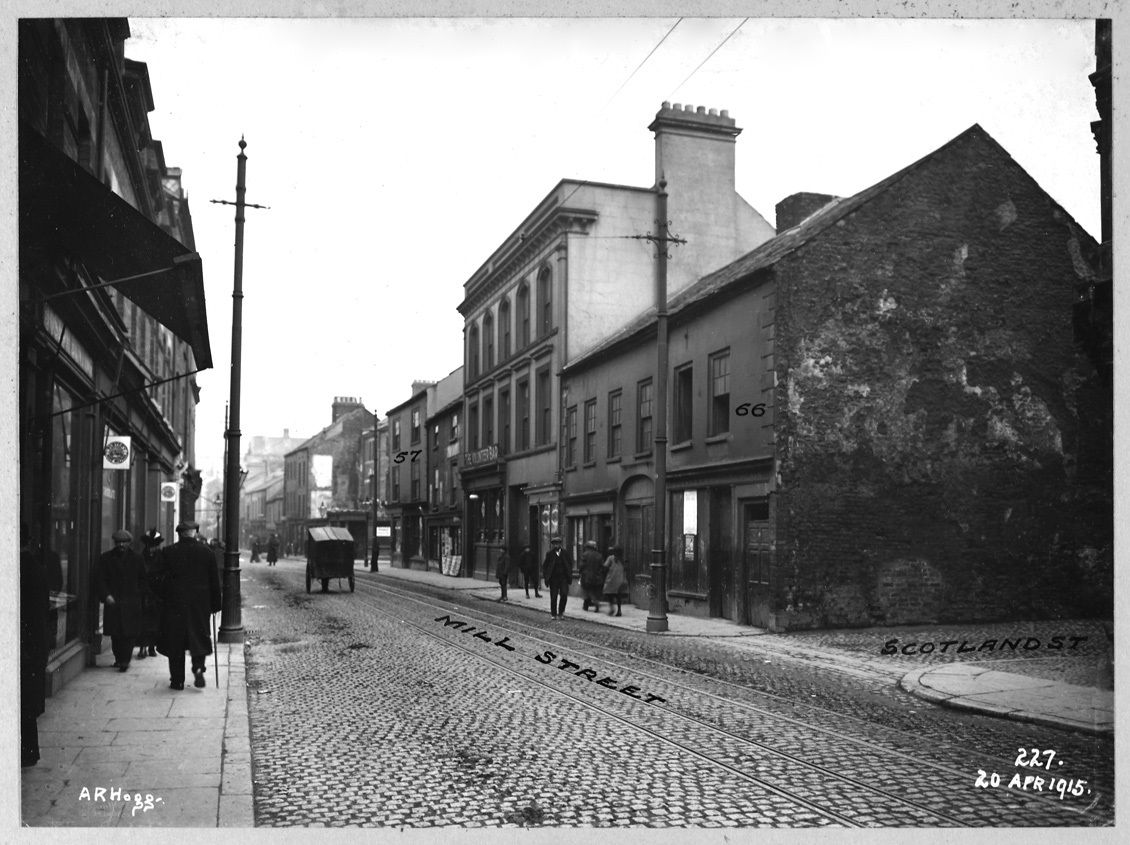

By the mid-nineteenth century Belfast’s population had increased to 100,000 and the town had six Dispensary Medical Districts, including Smithfield. Prominent streets included Mill Street, Bank Lane, Pipe Lane, Hudson’s Entry, West Street, Marquis Street, Winetavern Street, Samuel Street, Lennon’s Court, Charlemont Street, Smithfield Square and Chapel Lane. It was the most densely populated and overcrowded district in Belfast. There were countless small businesses, warehouses, slaughter-houses, and mills, numerous shops selling essentials and pawnbrokers, public-houses and grocer and spirits-stores proliferated.

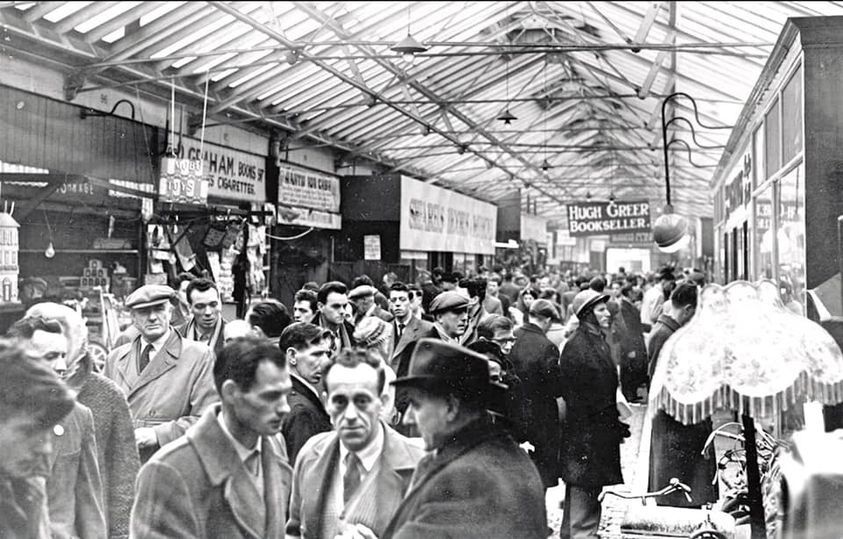

Smithfield Market and Square were the hub of the district. It was named and marked on a map of Belfast’s settlement as far back as the 1640s. Early references to Smithfield as a marketplace are found in the mid-eighteenth century and suggest it was functioning as an enclosed but open-air cattle and sheep market from the 1770s. In later years it was also selling wheat, barley and oats and hides and the ‘Belfast Vindicator’ of 1844 quotes cattle and sheep prices at ‘Smithfield’s Cattle Market’ for its Wednesday market-day.

With the 1848 Town Improvement Act, ‘Smithfield Market’ as then defined, was improved with the erection of enclosures and sheds of different sizes around the Square and a general upgrading of the market accommodation, with a defined list of goods that could be sold there, including hay and straw, turf, clothing, old and new furniture, meal, flour, vegetables, fish, delph/earthenware, tinware, livestock feed and more. Livestock, by then was no longer sold at Smithfield, with the relocation of ‘Belfast Cattle Market’ to lower Chichester Street.

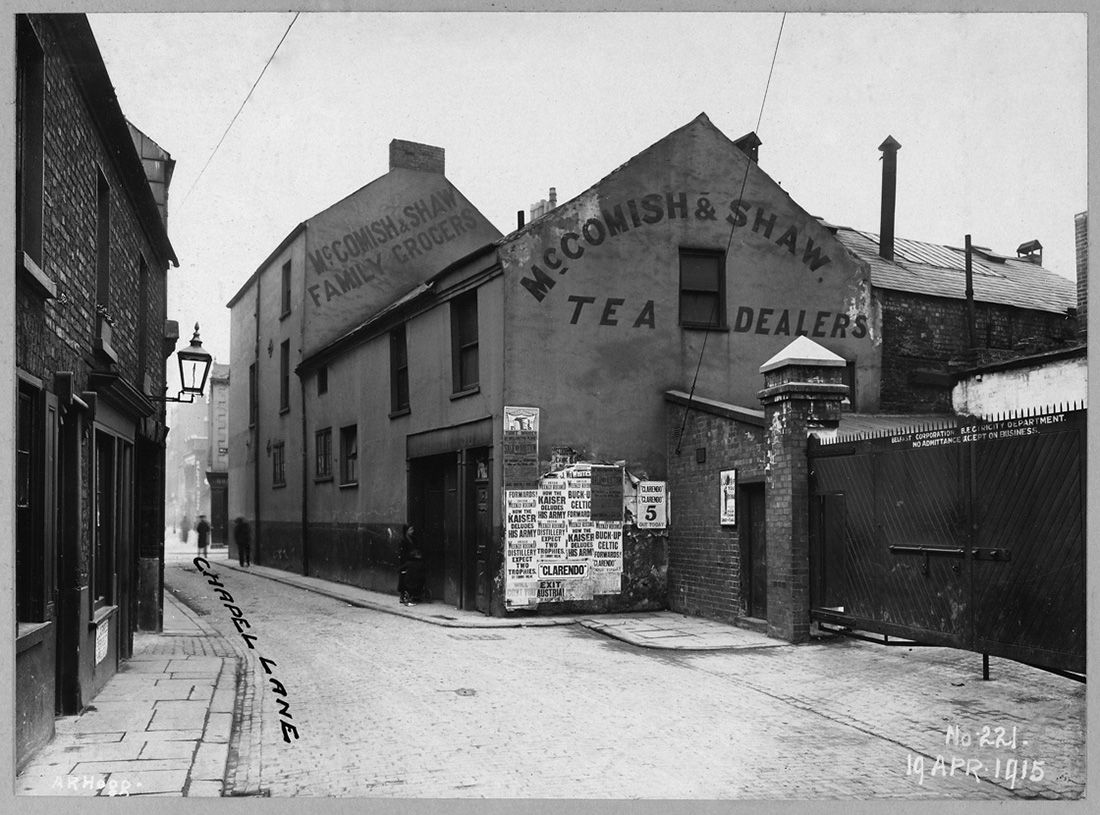

BYWAY: Kelly’s wine and spirit store in Bank Street, 1915, looking towards St Mary’s, Chapel Lane A.R. Hogg, Courtesy of the Deputy Keeper of the Records, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland LA/7/8/HF/4/221

Valuable insight into the community life of Smithfield is explored at first hand by the Rev. W.M. O Hanlon’s published accounts of 1852/53, ‘Walks Among the Poor of Belfast’.

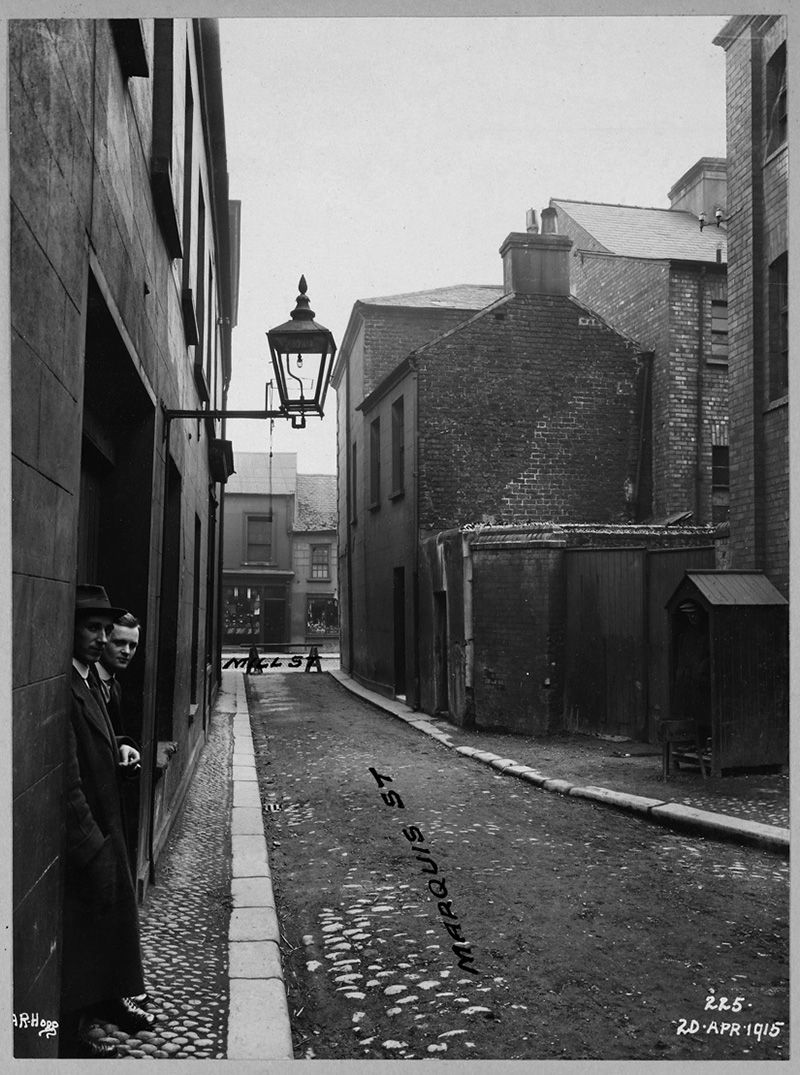

His commentary focuses on the social and sanitary deprivation of Smithfield and the social habits of the community he experienced there. The sanitary state of Marquis Street and its offshoot, McLean’s Court, were of particular concern, but Hudson’s Entry he described as “a complete den of vice and uncleanness, probably unsurpassed in what is called the civilised world.”

Equally the vast number of “drunkeries” (public houses – he counted twenty around Smithfield Square alone) and obvious excessive drinking among the people there were especially disconcerting to him. “They breakfast upon whiskey, and sup full of horrors upon the same.”

His accounts reveal his abhorrence at the extent of regular fist-fighting spectacles amongst young men, usually occurring at weekends in Smithfield Court. One instance he recounts is the vicious and bloody fight of two young lads in Hudson’s Entry: “...one of whom was backed by his mother, who, when her boy grew faint and feeble from loss of blood, spirited him on, by the promise of choice eatables... There stood the mother, with arms extended and hair dishevelled – a human fiend – urging on, by voice and gesture, her own child to murderous deeds, while the blood spurted over his tattered garments and fell upon the ground.” When a humane man tried to put an end “…to this atrocious spectacle, that mother turned upon him like a tigress, and seemed ready to spring at his throat for daring to interfere with her or her child.”

On February 16, 1847, the Northern Whig published assessments of Belfast’s six Dispensary Districts from their Medical Attendants. Dr R.F. Dill, responsible for the Smithfield district, said of it: “I am prepared to take any persons who may choose to accompany me, and I shall shew them scenes of wretchedness and poverty unsurpassed in any other part of our country.”

NARROW: McComish and Shaw grocers, Chapel Lane, Smithfield, 1915 A.R. Hogg, Courtesy of the Deputy Keeper of the Records, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland LA/7/8/HF/4/221

This assessment was a damnatory revelation of the extent of the sanitary evils in the heart of the town, not least Smithfield, and how vulnerable Belfast had become to the unfolding horrors of the Great Famine. The total number of Smithfield district patients for the year ending 1847 was 4,869, of which 1,533 were typhus fever patients and half this number came from just ten streets.

In 1849 Belfast was particularly hard hit by the cholera epidemic. Smithfield produced 458 cases in 1849, the highest number of the six dispensary districts of the town. Dr Malcolm’s report notes that in Lennon’s Court off Smithfield, cholera “raged with peculiar violence, every house on one side of this Court having been visited by it.” Medical attendants in that year from the district medical dispensary for Smithfield paid 2,096 visits and 6,158 prescriptions were administered. During the same years countless others, the true numbers still unknown, died of hunger, malnutrition and destitution.

The terrible suffering within the town during the Famine years is best illustrated by the description of one family visited by James Duffy in Smithfield, published in his letter to the Northern Whig, February 4, 1847. “I there saw a picture of destitution, the scene of which, if drawn by another, I would have concluded to have been laid in Skibbereen or Bantry. Of anything in the way of furniture the house was utterly destitute; and, to serve as a bed for the entire seven, there was only a filthy, damp wad of straw – the coverlet, a single piece of blanket. A rug which the family possessed had been pawned, a fortnight before, to procure food, as had also the man’s coat, shoes, shirt, and his boy’s trousers – in short, everything in the house which the pawnbroker would receive... and, even now, after something has been done by a few charitable neighbours, to save this miserable family from ‘death by hunger’ I fear that some of the number will fall victims to their previous sufferings.”

SNAP: Two men look to the camera in Marquis Street, looking towards Mill Street, Smithfield, 1915 A.R. Hogg, Courtesy of the Deputy Keeper of the Records, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, LA/7/8/HF/4/225

The fever epidemic in Belfast was a major trauma for its citizens, voluntary workers and medical services. A letter appeared in the Banner of Ulster on February 2, 1847, from John Boyd, Secretary to the Ballymacarrett Relief Committee, appealing for public donations. He outlined the dreadful circumstances in Ballymacarrett, comparing the scenes there with some of the worst to be found in the south and west of Ireland. Subsequently a widely-publicised controversy arose in the town between those who felt charitable funds raised in Belfast by the Belfast General Relief Fund for Ireland should be mainly spent helping Famine victims, the poor and destitute in Belfast. whilst others maintained that significant sums should continue to be sent for relief to the hardest hit places in Ireland where suffering was at its greatest, not least in the west and south of Ireland. The ‘Temporary Relief Act’ in March, establishing a network of soup kitchens in Ireland for poor relief, fuelled the debate that more resources should be directed from local charitable donations and relief committees to support Belfast’s poor and sick, as the town’s own circumstances deteriorated.

Medical Attendants and concerned citizens increasingly began to inform the wider public that charitable support in funds, clothing, food, as with the available resources of medical care, were insufficient to meet the levels of need in Belfast. They believed that the true extent of actual suffering and destitution in the town was unknown and likely to be much more severe than official estimates indicated. It was essential that reliable and accurate information should be systematically gathered to improve planning and targeting for health care provision, food and blankets in the town’s worst affected districts. The six Medical Attendants of the dispensary districts subsequently provided public reports of the extent of distress in their respective districts.

The public’s concern was illustrated in another letter from James Duffy, published in February in the Northern Whig: ‘Destitution in Smithfield’. “Were you, Sir, to visit the lanes and courts – the dreary fireless habitations of the roomkeepers, and other wretched inhabitants of Smithfield Ward – hungry, yet uncomplaining – you would find that if returns of destitution and disease, in Belfast, were at present made, they would, indeed, be melancholy statistics. We weep over the misery, and death, and horrifying scenes of famine, presented in the reports from Skibbereen and Bantry, and Dingle and Skull, and our hearts and purses open to the appeal; but have we no tears for the famishing, the dying in the cold and dirty avenues leading from our own Smithfield, and Millfield, and Hercules Street, and North Street, and Barrack Street? I am one of those who would contribute, to the utmost of my means, to relieve my suffering fellow creatures in other places; but, at the same time, it is no reflection on any man’s benevolence to say, that ‘Charity should begin at home.’”

FAMILIAR: Bustling Smithfield Market in the 1950s; but the district has a much darker history of which little is known Courtesy of Belfast Historical Photographical Society

Subsequently a greater degree of cooperation between charitable relief committees and medical charities occurred, with attention directed to Belfast and to the hardest-hit areas of Ireland, according to need and levels of distress. For example, on March 31, 1847, the General Relief Committee made grants available. of £250 to the Belfast Day Asylum, and £1000 to the voluntary Belfast Soup Kitchen Committee. The Belfast Ladies’ Association for the Relief of Irish Destitution provided a grant in 1847 to the Ballymacarrett Relief Association and grants to the Belfast Ladies’ Society for Relief of Local Destitution to support their industrial school and other charitable work.

After the Famine, health and sanitary reform was slow in coming. In April 1865 the News Letter showed how little had changed in the Smithfield district, despite the various Town Improvement Acts, advances in medical knowledge and the movement for social and sanitary reform, stating: “There is none viler, more squalid, more dangerous in any town in Europe. Penetrate to the interior of some of the houses in some of the lanes... and the sights which slowly reveal themselves excite profound commiseration, and yet evoke an unconquerable horror.. .In one room a whole family were huddled without fire and with scarcely any covering. The only bedding in the room was some loose straw in a corner; and upon a little deal table lay the body of an infant, dead, covered with a small piece of calico. Other children sat up... cowed and silent, in the presence of the mystery of death, and the wretched parents knew as little where to procure food for the living as a last resting place for the dead.”

Describing Smithfield’s alleys and courts as “labyrinths of horror’ the News Letter pronounced decisively: “There is but one remedy for the evil and the sooner we prepare to apply it the better. The whole nest of horrors must be swept away.”

©Brendan Muldoon, 2022.