“…there is hardly a parish of any considerable extent in which there may not be found some unfortunate human creature who, if his il-treatment has made him phrenetic, is chained in the cellar or garret of a Work-house, fastened to the leg of a table, tied to a post in an out-house, or perhaps shut up in an uninhabited ruin; or, if his lunacy be inoffensive, left to ramble, half-naked, half-starved, through the streets and highways, teased by the scoff and jest of all that is vulgar, ignorant or unfeeling.”

Such was the plight of insane poor in 18th century Britain and Ireland when mental illness was shrouded by ignorance, fear, superstition and religious interpretations, (afflictions by God); the treatment of those afflicted with so-called ‘madness’ notoriously hideous and cruel.

Early 19th century Ireland had virtually no public or state provision for people deemed to be mad or insane. Without family support, the fate of the insane poor was left to the charity of the humane public, religious and charitable bodies, or so-called ‘Houses of Industry’, originally set up by the 1772 Act passed in the Irish Parliament to support the aged poor, destitute, the sick, deserted women and children; with separate limited provision (cells) for lunatics, who were segregated from the other inmates.

In 1817, Thomas Spring-Rice, Irish Liberal MP from 1820, completed an inspection of various Houses of Industry in the south of Ireland during the British Government’s Select Committee Inquiry into the numbers of insane persons per county and standards of care provision. He reported the prevalence of atrocious conditions for the insane poor and called for reform on the treatment of the insane in Ireland. The 1817 Inquiry and his report were highly influential in the subsequent passing of the 1821 Lunacy (Ireland) Act, that provided for the establishment of a network of ‘district lunatic asylums’ throughout Ireland, eventually 22 in total, including the Belfast Asylum (1829).

After the passing of the 1821 Lunacy (Ireland) Act mental illness came to be regarded differently. Asylums were seen as places of ‘care’, not places of ‘punishment’. Doctors were influenced by the positive techniques of so-called ‘moral treatment’’, pioneered by William Tuke an English philanthropist and Quaker (1732 –1822), at the ‘York Retreat’ for the Insane, in England. ‘Moral Treatment’ was an approach to mental disorder based on gentler, more humane care, improved surroundings, and positive staff-patient relationships that influenced asylum care and practices for most of the 19th century; an approach intended as potentially leading for many inmates to rehabilitation and recovery.

Despite this apparent progress, knowledge and understanding of mental illness remained in its infancy in 19th Century Ireland. Psychiatrists were commonly known as ‘alienists’, likely originating from the French noun ‘alieniste’ or alienist in English, referring to someone who treated the insane. This reflected the official view of the medical profession that persons suffering from mental illness were thought to be ‘alienated,’ not only from the rest of society but from their own true natures.

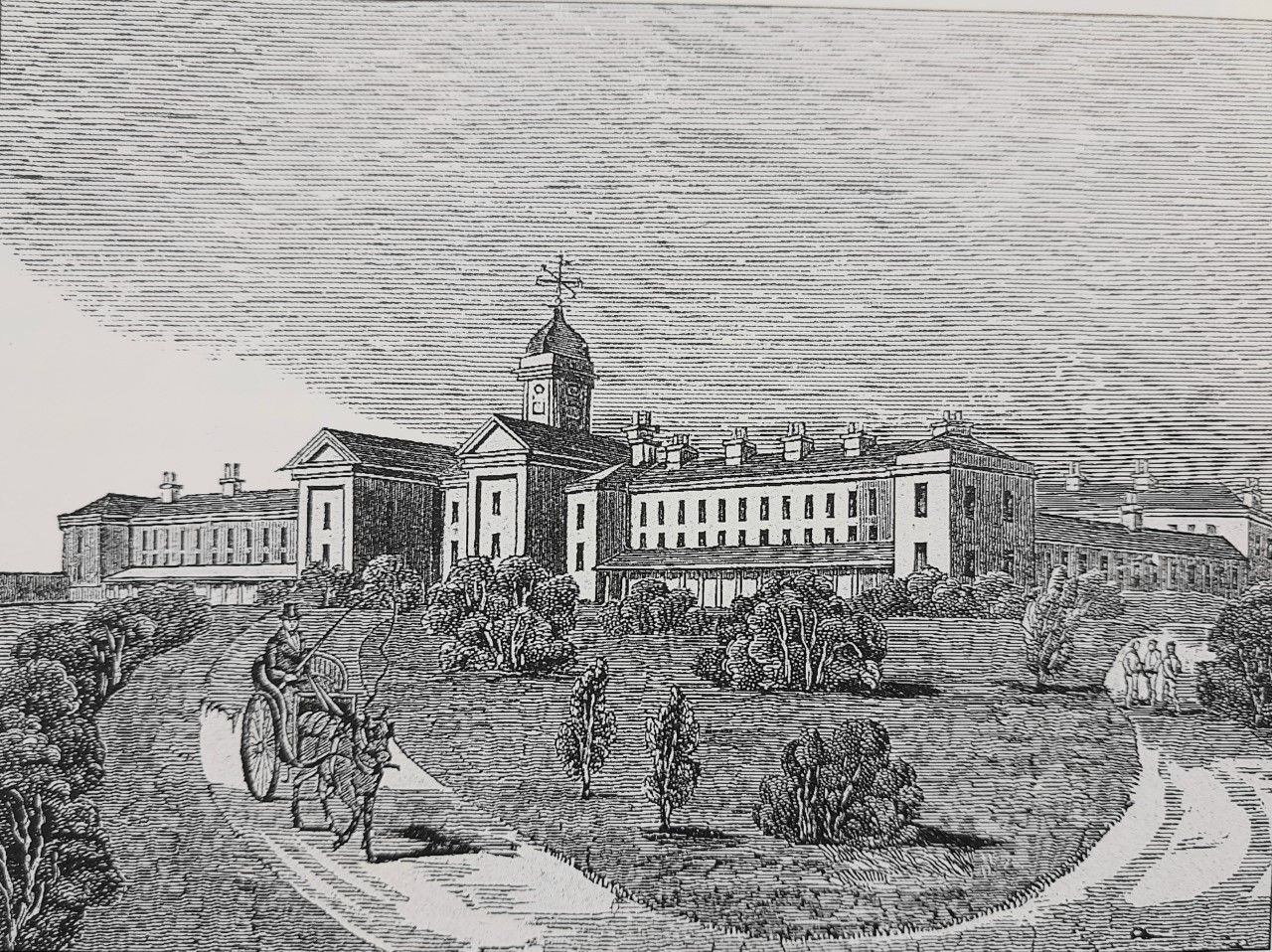

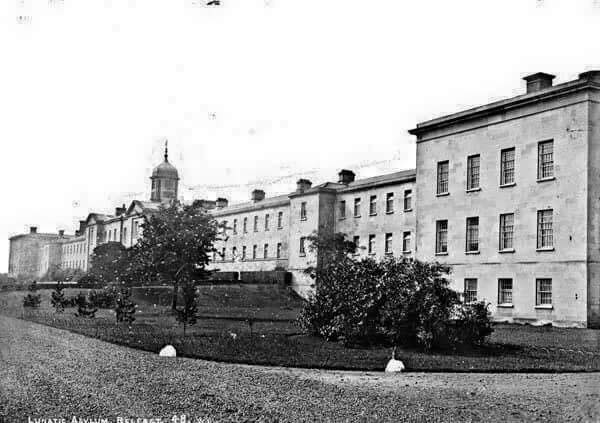

The Belfast District Lunatic Asylum 1829-1858

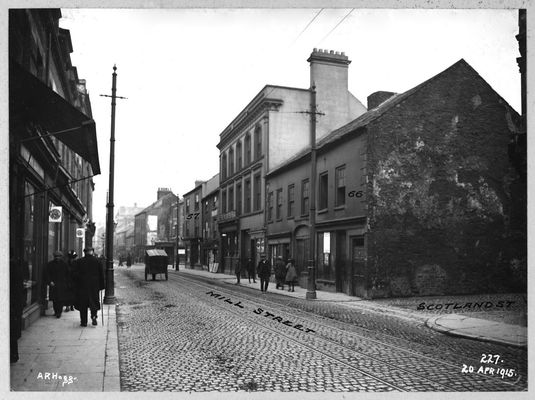

In Belfast, farmland was purchased on the Falls Road (present day site of the Royal Victoria Hospital), for the construction of Belfast District Lunatic Asylum, which was officially opened in 1829. With an extension in 1836, it could provide total accommodation for 250 inmates, with male and female inmates strictly segregated.

NI Ordnance Survey Map of Belfast 1923 - Belfast District Lunatic Asylum, Falls Rd, in grounds of RVH, one year before demolition

After the asylum’s first physician retired, Dr Robert Stewart was appointed its Resident Medical Physician (1835-1875) becoming the first doctor of a district Irish asylum to simultaneously hold the post as its Managing Superintendent. During his 40 years tenure the asylum gained an illustrious reputation with clinicians travelling from America and Europe to visit it. Dr Stewart was later described as the “Father of the Irish Asylum Service” by the Medical Journal of Mental Science. His success applying a therapeutic environment based on ‘moral treatment’ was acknowledged in April 1846, when the eminent William Tuke, after visiting the Belfast Asylum, said: “I have gone through this Hospital for the Insane with a high degree of satisfaction… there is an air of ease and comparative comfort in the general aspect of the patients, which has given me the most favourable impression of the principles of management, which are carried out by Dr Stewart in this establishment.”

Dr Stewart’s Tenth Annual Report of the Asylum in June 1840, offers valuable insights into its therapeutic practices and patient care. An issue that strongly emerges was the social circumstances of patients prior to their illness and admission – primarily the physical and psychological effects of crushing poverty – associated lifestyles (chronic alcohol abuse and malnutrition), over-crowded housing and the nature of ‘family circumstances’, collectively seen by contemporaries in the medical profession as an ‘incubator for madness’.

There were 109 new admissions for the year ending March 31, the overall total being 227. The majority were aged between 20-60 years, the male/female ratio almost equal. The ‘causes’ assigned for insanity were categorized as ‘moral’ or ‘physical’. ‘Moral’ causes included: domestic misfortunes, grief, poverty and reverses, jealousy, religious excitement &and enthusiasm, loss of property, fright (mainly affecting females), apprehensions relating to a future state, pride, remorse, fear of want. Physical causes included: intemperance (mainly affecting males), bodily debility, effects of fever, hereditary, head injury, puerperal affectations (post-natal illness), abuse of mercury. Other reports added causes such as ‘over study’, paralysis, irregular habits (physical) or listed as ‘unknown’. The profound reality was that anyone admitted to an asylum in 19th Century Ireland was deemed to be ’insane’.

The application of ‘moral treatment’ was highlighted with how the asylum saw the restorative and curative effects for its patients of supervised programmes of outdoor pursuits and exposure to fresh air, a “moral and restorative means of cure”. There were 182 out of 227 inmates actively involved in various activities in and outdoor, including gardening and agricultural pursuits in the large adjoining gardens whilst others indoors were involved at weaving (male) spinning (female), or sweeping yards, assisting in the laundry rooms, kitchens etc… “the remainder… whose mental and physical condition are so enervated as to altogether preclude the possibility of their undertaking the simplest employment". The large gardens also had divided areas – ‘airing yards and piazzas’, in which inmates were at liberty to move about as they pleased, “this doing away as far as it practical, with all appearance of restraint, or of their not being entirely free agents” to enjoy the outdoors and fresh air.

Engraving of Belfast District Lunatic Asylum 1829, after official opening

Criminal Lunatics

Seven of the new admissions were ‘criminal lunatics’ committed to the asylum when during sentencing they were declared insane. This became a highly contentious issue among the asylum authorities in Belfast and elsewhere in Ireland – asylums they asserted were medical facilities not prisons. Accepting genuine cases of mental illness precipitating crime, they found obvious cases of convicted criminals feigning madness to be committed to the asylum as insane, rather than face prison, deportation or evade capital punishment.

Dr Stewart asserted that district asylums were set up to provide support and care for the “distressed lunatic poor” for temporary periods, to help soothe the diseased mind of medically ill people within a supportive retreat setting, but were not designed for providing restraint and custody for convicted and insane criminals who should be placed in purpose-built accommodation, potential highly dangerous individuals. He advocated a Central Criminal Lunatic Asylum for all Ireland, eventually achieved with the Central Criminal Lunatic Asylum (Ireland) Act 1845 and opened in Dundrum, Dublin, in 1850; the priority given to the most dangerous criminally insane – murderers.

Use of Restraints

Dr Stewart believed that the complete abolition of the use of ‘physical restraints’ for some patients, no matter how desirable on humane grounds, was neither practicable or realistic but “utopian”. He cited cases at the Belfast Asylum when patients had ‘pleaded’ for the placing of restraints to protect themselves against self-harm and another case of apparent ‘demonic possession’ of a patient where restraints were absolutely necessary as a last resort.

“A female patient... having a strong propensity, in her maniacal paroxysms, to shed, not her own blood, but that of others; and if there be such a thing as 'possession' in the present day, this female doubtless, is thus, in a measure, unhappily afflicted; for; when in an excited state, a more demonic spirit, in conduct and language, could scarcely be paralleled, even in the Scripture accounts. She will, at times, plead in extenuation, of some violent act she has committed or attempted to commit, that she could not help it, for that the devil had her completely in his power.”

Conversely, he was highly critical of the alleged ‘widespread’ use/abuse of restraints and their horrors in English asylums.

“A strait waistcoat is brought, a struggle ensues, another keeper arrives; and, in the attempt to put on the jacket, the patient gets very roughly used. He resists, swears, kicks and bites; the keeper or keepers kneel on his body, thrust their knuckles into his throat, beat him and bruise him until they succeed in overcoming him. Then, the jacket is tied so tight he can scarcely breathe; his legs are fastened together, either with iron or leathern hobbles; and, to sum up all, if he has resisted stoutly, he is chained to a wall, in a small dark room, and the door is closed upon him. At bed-time, instead of being allowed to go to his proper bed, he is thrown upon straw, and his hands and feet are chained to the bed-stead.”

Straight Jacket used in Irish asylums mid 1900s

He stated: “If this be a 'faithful picture' of the method adopted, in this age of humanity and great social refinement… in the English Lunatic Asylum, it cannot be too emphatically stated, that such is “never necessary, never justifiable, and always injurious in all cases of lunacy whatever.”

The report aside, surprisingly, the inner workings of the Belfast Asylum did not appear widely known by the general public. The ‘Banner of Ulster’, wrote (25/09/1849): “…Those who have made the Falls Road the scene of their evening walks… must have been struck by the sombre looking appearance of the building whose belfry clock proclaimed to them, in lively tones, the passing hour. For 20 years the edifice has stood there, encircled by lofty walls, and tenanted by the most pitiable specimens of aberrated humanity. It is, ‘The Belfast District Asylum for the Insane Poor’. The public, generally speaking, know no more.”

Nevertheless, valuable insights into the conditions of life for the patients exist in accounts of personal visits to the asylum by newspaper reporters.

The Belfast Commercial Chronicle, November 15, 1845, reported an open evening extravaganza for invited members of the public, dignitaries and reporters, hosted by the management and presented by the patients with various entertainments. The evening included by the patients an instrumental piano and violin performance and a dance extravaganza, “one of the most extraordinary dances it was ever our lot to witness.”

The reporters met with some individual patients, one who displayed obvious symptoms of mental illness with delusions that he was held prisoner at the asylum as part of a conspiracy, as he was the real heir proper to the thrones of England, Scotland and France. Whilst another, said to be a graduate in Classics of Trinity College Dublin, happily recited long passages from Greek and Roman literature and spoke about his passion for Greek tragedy.

The Banner of Ulster, of September 25, 1849, reported that their experience “was such as to lead us to the belief that were the institution better known, its great value and importance would be more fully prized.” … “The doors are all open, the rooms carpeted, the furniture magnificent, the walls lined with maps and engravings.”

They visited the spinning rooms, with 20-30 females in each, who were generally cheerful, engaged in spinning, knitting, flowering or making dresses. Elsewhere, “…insanity presented itself in some of its wildest features; one old gipsy looking woman, although seemingly the very soul of good nature, being beyond all question lamentably astray in her judgement. She momentarily shouted, sung, cursed, spat on her companions, or jumped about the room in a frantic state, making several whom she regarded as her children – enact with her some of the most ludicrous scenes.”

Belfast Lunatic Asylum, early 1900s, Courtesy of 'Images and Memories of Old Northern Ireland Pre 2000'

In the male department, they met several patients displaying “striking peculiarities” of mental illness, one who believed he had been ‘Provost of Trinity College Dublin’, was the most learned man in Europe and King of Great Britain, who sought the welfare of all classes of his subjects by removing all taxation. “I have been several times killed, but such is the ignorance of this world, that no one, not even Dr Stewart, can conceive how, being dead, I am still alive.”

Periods spent in asylums varied, lasting months, years, even decades, with the obvious dangers of institutionalisation. For numbers of patient’s asylums became, in effect, ‘permanent homes'. The Newsletter (24th July 1858), reported the death that year of the first inmate admitted into the Belfast Asylum in 1829 who had remained there for 28 years. During her time in the asylum both her son and daughter had also been patients. Her son made a good recovery but her daughter died under treatment, prior to her mother’s passing. Apparently in neither instance would they admit that they were her children. The Newsletter added poignantly, “… but who, nevertheless, and more especially in the case of her daughter, manifested, in various ways, that a mother’s love and feelings, however obtuse and dormant they might have become from the effects of long continued mental disease, were still by no means obliterated.”

The history of the Belfast Asylum was a long but never unremarkable journey until its eventual closure in 1913. In 1849, the Banner of Ulster reflecting on the lack of general public awareness of the inner life of Belfast’s Lunatic Asylum advised caution, stating:

“Dethroned reason, in the various phases in which it presents itself, is not a fit subject for the idly curious or the thoughtlessly inquisitive.”

Ironically, during the 19th Century, even among the medical profession, the nature of insanity was never understood. At its end it remained a mystery.

Brendan Muldoon ©2022